5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes James Cahill on Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The School of Night, Becca Rothfeld on C. Thi Nguyen’s The Score, Niela Orr on Madeline Cash’s Lost Lambs, Toby Litt on Elizabeth McCracken’s A Long Game, and Dwight Garner on Jim Paul’s Catapult.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“There are numerous instances, small or large, of Kristian’s callousness. But he is also cerebral and imaginative. Part of what makes the novel riveting, even in its more eventless phases, is Knausgaard’s ability to inhabit the mind of such a person. The emergence of Kristian’s faintly sociopathic nature is mirrored in his burgeoning artistic vision.

…

“This fourth novel in Knausgaard’s Morning Star sextet (the final two are already available in Norwegian) squarely inhabits the series’s prevailing mood: realism undercut by a hint of the preternatural. There is a coolly undemonstrative aspect to the writing. Often, the significance of things lingers just beyond grasp, with events appearing both arbitrary and ordained.

…

“In Martin Aitken’s translation, the prose is fluent and nimble, the imagery possessed of a steely melancholia. Partly by dint of its setting in 1980s London, the novel carries resounding echoes of Iris Murdoch: Kristian shares much with the smug, sybaritic Charles Arrowby of The Sea, The Sea (1978), and with the self- obsessed Bradley Pearson of The Black Prince (1973). Like Pearson, he proves to be snared in machinations beyond his understanding. Allusions to the Faustus story and to Marlowe (notoriously murdered in Deptford), not to mention various other literary forebears (including an invented Austrian poet), invest The School of Night with a shimmering intertextuality that befits its characters’ fascination with mirror images. ‘There’s something so unsettling about mirrors,’ says Hans. ‘When we look into our own eyes, who do we see?’

In the novel’s final third, the setting shifts to the early twenty-first century and Kristian’s life as a renowned photographer in his forties. It is a necessary move, guiding us towards the devastating downfall that the opening presaged, but jolts us discomfitingly away from the simmering unease of the 1980s sections. An on-stage talk with an art critic—what seems like a formulaic exposition of Kristian’s photography—becomes the occasion of a fatal revelation. The ensuing tale of scandal and comeuppance frames the earlier portrayal of the artist as a young man. That older tale, however, is the novel’s essence—a realist affair laced with the faintest suggestions of myth, the occult and the perverse operations of fate.”

–James Cahill on Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The School of Night (Times Literary Supplement)

“This subtitle, with its whiff of self-help and didacticism, sells Nguyen’s profound, rigorous and frequently beautiful book short. The Score has an ambitious mission. It seeks to explain why the constraints imposed by scoring systems in games are so liberating, while the constraints imposed by institutional metrics are so deadening. In doing so, it aspires to explain a quintessential contemporary tragedy: the extent to which optimization has gutted our lives. Even without this larger argument, The Score would brim with local insights. Nguyen is a connoisseur of games, and his musings about them are ingenious and entertaining.

…

“Quite anomalously for a work of philosophy, The Score is socially attentive, historically literate and imbued with sensual glee. It is exuberantly eclectic, full of passionate digressions into the history of algorithms or the nature of classification systems or the workings of skateboarding competitions. All this would make the book well worth reading even without its argumentative pièce de résistance, its inspired comparison of games and institutional metrics—those pesky grades that teachers append to homework, the rankings we attach to colleges, the often simplistic measures we use to assess health.

…

“The urgent question posed by The Score is one a student started asking herself after she attended one of Nguyen’s lectures. She looked around at all the metrics that reduced her to a daily step count, a number on a scale, a score on a test, and she wondered: Is this the game you want to be playing? Her answer was no. I think readers of Nguyen’s forceful book will agree.”

–Becca Rothfeld on C. Thi Nguyen’s The Score: How to Stop Playing Somebody Else’s Game (The Washington Post)

“There was a point in the 1990s when diagnostic pop culture about the malaise of the American suburbs ruled the day: in radical television, à la The Sopranos and Freaks and Geeks; novels, many of which were adapted for the screen, like Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm and Tom Perrotta’s Election; films like American Beauty and entries from Todd Solondz’s oeuvre, featuring weirdos and misunderstood kids, like in his masterpiece, Welcome to the Dollhouse. This media seemed to be telling us what has now become something of a truism: that there is a structural, psychic rot in the foundation of these communities, many of which were formed as a result of white flight. Also, too, that the spectacular boredom of the burbs wrought a complementary spiritual and social inertia. Amid depictions of a lost nation, scrambling in the aftermath of the Columbine shooting and September 11, soliciting a spectrum of jingoism and conspiratorial thinking, the suburbs were ground zero for overheated cultural analysis. Never mind the nihilism and repression and confusion that ran rampant in the country’s cities and rural areas—there was a special psychic vortex here, the messaging went. But that was then. What do the suburbs have to teach us now? As a symbol, do they mean something different in the second Trump era than they did in the Clinton years? The writer and editor Madeline Cash seems to be interested in these questions.

…

“In this antic era, Lost Lambs offers an update on Pynchonesque paranoia, featuring lonely people in anonymous suburbs who get drawn into overlapping conspiracies that crisscross the map. One generalization about the suburbs is that the particular discontent burbling there was entirely unique. ‘People like them don’t understand people like us,’ one character says, then points up to the ceiling, ‘to the suburbs above.’ In a world in which that kind of alienation is pervasive, Cash’s look is refreshing. In some older portrayals of paranoia, in books by Dostoevsky, Philip K. Dick, and Pynchon, boys and men took up the most space; they were the intrepid playable characters in the games Harper likes, attempting to rescue the insipid princesses and other female victims.

Cash’s twist in Lost Lambs makes conspiracy a practice honed by young girls, the kinds of people at the center of Pizzagate and rap beefs and the Epstein files. In lyrics and legal briefs and discussion boards, young girls are pitied, projected on, operationalized, and even sometimes seen, in grisly, half-redacted pictures, but hardly ever heard. But we can listen to Cash’s characters, and some of them say, ‘I told you so.’ In her hands, cultivating counter-ideologies is a way for the vulnerable to hone their intuition, to trust themselves. Lost Lambs is a confident if uneven start for a morbidly funny writer. A novel is a minor conspiracy unto itself, a frenzied assembly of story and figures and motivations; even if this one doesn’t totally cohere, like a good conspiracy theory, it offers something to think about and more than a few laughs besides.”

–Niela Orr on Madeline Cash’s Lost Lambs (Vulture)

“With A Long Game, Elizabeth McCracken has come pretty late to the party. And she’s determined to liven things up. For a start, she does not agree with craft books, either their sentiments or their usual tone: ‘chipper, cheerleaderish, generally with an encouraging second-person narrator meant to make the whole exhausting process of writing a book seem possible.’ It’s obvious she’s thinking of such motivational titles as Walter Mosley’s This Year You Write Your Novel.

…

“…she’s not your usual wise old literary hand. Instead, she is naughty, perverse, quietly exhibitionist and bracingly unashamed. She reminds me of the teenage older sister of one of my best friends at school. She lived in a world I didn’t. She behaved or misbehaved just as she chose; and sometimes she did the wrong thing, the bad thing, because it was more interesting. McCracken’s is the naughty older sister view of writing. And I agree with it. Writing isn’t about compiling a list of rules and then obeying them. If it were that, then none of the really great writers I’ve ever read would have been interested in it. Not for half a day. Writing is a form of sustained mischievous truancy. It’s not about being good.

This attitude will be amazingly freeing for many rule-haunted writers. If you are being poisoned by a particularly cliched piece of workshop feedback, ‘Show, don’t tell’ or ‘Write what you know,’ McCracken will supply an antidote. It will be intense, distilled from experience, and the inoculation may cause you pain. But afterwards, you’ll stop sweating and shivering, and get on with living. Here McCracken is on that most hated and hackneyed piece of advice, ‘Write every day’: ‘Every-day writers have a clear answer to the question, How will you get your work done? Me, I harness the power of my own self-loathing.’ Not your usual piece of creative writing workshop advice, but true to the particular insanity of this scribbled life.”

–Toby Litt on Elizabeth McCracken’s A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction (The Guardian)

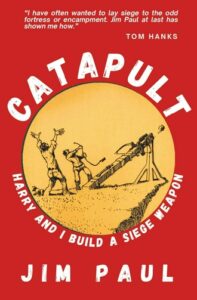

“When Jim Paul’s book Catapult: Harry and I Build a Siege Weapon was first published in 1991, I bought and read it immediately. It’s not that I cared so much about seat-of-the-pants engineering or medieval warfare. But I knew a great title when I saw one. Over the years, Catapult has become a cult book, a literary outlier. It has provided offbeat solace for readers who like good capers and stupid and futile gestures. I’m happy to report that this modest and shaggy book, newly republished, is as winning today as it was back then. It deserves a second moment in the sun, a new generation of eyeballs.

…

“In Paul’s telling, the project expands intellectually—the way a drywall anchor opens to offer support from the back. Catapult might be about seeing a complicated D.I.Y. project through, but it’s also about the combined histories of engineering and warfare, about male friendship and about the innate impulse (what else did kids do before the internet?) to chuck rocks at things. If Paul and Harry were embarking on a similar project today, they would have their pick of how-to videos to consult. Monster Energy might’ve signed on as a sponsor. Back in the ’80s, though, research was analog. Part of the fun of Catapult is watching the pair move about—like Michael Douglas and Karl Malden in The Streets of San Francisco, but more slowly and in cheaper cars—in search of information and parts.

…

“Catapult works because of its aw-shucks quality. Despite the sidebars into prickly themes, the book never strays far from what its subtitle promises. We watch two young men, men who can use ‘a therapeutic measure of irresponsibility,’ collaborate on the backyard project of a lifetime, essentially for the fun of it. And fun, Auden said, is ‘the only good reason for doing anything.’”

–Dwight Garner on Jim Paul’s Catapult (The New York Times)