9 Books About Chaotic White Girls Getting High

There is something particularly annoying about chaotic white girls, isn’t there. I say this as a recovering chaotic white girl myself. The heady cocktail of privilege and self-pity, the culturally approved beauty, the patriarchal casualty. During my harrowing yet transformative early weeks and months of early sobriety, I was compelled to read all the books in this problematic genre that I could get my hands on. It was research. It was work. It was also its own kind of addictive play: a morbid fascination.

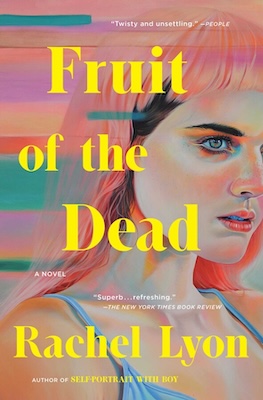

My second novel Fruit of the Dead follows Cory Ansel, an 18-year-old contemporary Persephone, to the seductive underworld / private island of a super-wealthy pharmaceuticals CEO whose company manufactures a seductive (fictional) drug under whose addictive spell Cory soon falls. Unlike my heroine, I was not so into drugs. Pot was great until it made me paranoid, psychedelics transcendent until my mind betrayed me. Speed was merely useful as a remedy for hangover. My drug of choice was simple, stupefying alcohol. Your garden-variety daily drinker with a broken memory and unstable personal life, by the end I was having my first drink of the day alone at

10 a.m. I drank to wake up and to pass out at the end of another queasy, troubled day. I drank to be alone, to be with people, and to try to drown the shame of drunk faux pas. By the end, my drinking was not cute or fun and yet, like so many in early sobriety, I missed it badly; I was plagued by the delusion that it had made me glamorous. The earliest paragraph of Fruit of the Dead that I remember writing was a kind of elegy for the altered state. It appears now in the last third of the book, when Cory is drunk and tripping on her new favorite drug:

“Her brain is slow. Her eyelids and limbs are heavy. Blue night snuffs out sunset’s fire, and the leaves above her shiver in the moonlight, concealing then revealing the ancient blazing stars. Everything is breathing, everything whispering. Lying on her back on the grass, she thinks the allure of the drug and the drinks . . . is like the allure of a cave full of diamonds, a glorious, luxurious, protected place she can drawl deep into, out of the moonlight, out of reality. The air may be stale in there, the light false, but it is beautiful and she is beautiful, too, inside it—and completely, deliciously, fearfully alone.”

Here are nine novels and memoirs which live, in part, in that isolated cave of diamonds. Which interrogate, explicitly or implicitly, the thrilling, thorny intersection of whiteness, femaleness, and substance use/abuse. Though most of these books circle the painful issue of addiction, they are not all addiction narratives. A few arguably celebrate their characters’ trippy altered states, evoking their highs with densely poetic, psychedelic language. Additionally, they all feature white, female protagonists of varying degrees of economic and social privilege. The on-page transcendence of these girls and women alternately moves, transports, and vexes the reader, demanding: What are the stakes of substance-enabled escapism, when the would-be escape artist has led, by any objective measure, a pretty charmed life so far?

Lit by Mary Karr

The godmother of all contemporary addiction memoirists, Mary Karr writers with a voice as compulsively readable as her story is painful. A recounting of the end of Karr’s marriage and the beginning of her sobriety, Lit begins with a prologue entitled “Open Letter To My Son” and nine inescapable words: “Any way I tell this story is a lie.” This book was one of the first addiction memoirs I consumed in early sobriety; I went on to become a joyful Mary Karr completist. If you haven’t yet had the pleasure of reading her work, Karr’s other books—Cherry, The Liars’ Club—are all equally wry, self-deprecating, and moving. N.b.: Beginning and aspiring memoirists, do yourselves a favor and read her book The Art of Memoir, staple of another genre, the writer on writing.

We Were the Universe by Kimberly King Parsons

Now and then a recovering addict will use the phrase “God-shaped hole” to describe the gaping maw into which she used to pour her substance(s) of choice. Parsons’ protagonist Kit—who is, like a young Karr, a mother and Texan—walks through the world with a bleeding, aching hole shaped like her recently deceased addict sister. The book is not an addiction narrative so much as a grief narrative about a beloved addict—but to describe it that way undersells its conversational tone, its wit, its humor. It is funny, horny, psychedelic, sad. It hooked me with its gorgeous, trippy prose, then sank me with a moving, unexpected twist in its final chapter.

The Guest by Emma Cline

Liska Jacobs’s review of Cline’s 2023 novel in The New York Times Book Review noted the echoes therein of John Cheever’s famous short story about alcoholism, memory, and loss, “The Swimmer,” published in 1964. “Like Cheever’s short story,” Jacobs wrote, “Alex’s beachside journey is a kind of modern-day Homeric odyssey, doomed by the hero’s own self-erasure, but also by an essential imbalance of power.” Like Cheever’s Neddy Merrill, Cline’s protagonist Alex is a whim-driven, substance-abusing dilettante who is, on a deep level, unknown to herself, and whose journey across the Hamptons’ moneyed landscape leaves behind her a wake of destruction. It is Alex’s very femaleness however which defines her best—which at once supplies and undermines what power she has. As she uses the influence of sex and of her sex to gain access and to manipulate, she too is used, by the novel, to interrogate the inherent emptiness and reflectivity of young womanhood itself—or its performance.

Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, The Flesh, and L.A. by Eve Babitz

Babitz’s collection of ten deceptively light, discursive essays about LA in the 1960s and 70s was published in 1977. Required reading for anybody curious about this genre, the book is pure hedonistic pleasure. Here are sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, peppered through with a laundry list of paramours and easily dropped names, including Jim Morrison, Paul and Ed Ruscha, and Marcel Duchamp, with whom she was famously photographed playing chess, nude, in 1963. Babitz is the iconic LA babe: pretty, witty, and restless. “I was impatient with ordinary sunsets,” she writes. “I was sure that somewhere a grandiose carnival was going on in the sky and I was missing it.”

Postcards from the Edge by Carrie Fisher

This heartbreaking, delirious, voice-driven novel—by another Hollywood princess—was published in 1987. Through letters, journal entries, dialogues and monologues, it follows actress Suzanne Vale, just out of rehab after an overdose, in a slow, difficult, but always entertaining effort to piece her life back together. Reader be forewarned, however: in the novel, Suzanne’s conflicted relationship with her mother is far less central than in Mike Nichols’ delightful 1990 film adaptation of the novel, starring Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine. For a more candid, nonfictional look at Fisher’s relationship with her mother, actress Debbie Reynolds; father, singer Eddie Fisher; the relationship between Fisher and Elizabeth Taylor that broke up their marriage; Fisher’s drinking, stardom, and more, read her equally moving and irreverent 2009 memoir, Wishful Drinking.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

Jia Tolentino wrote in 2018 that “Ottessa Moshfegh is easily the most interesting contemporary American writer on the subject of being alive when being alive feels terrible. She has a freaky and pure way of accessing existential alienation.” Moshfegh’s protagonists are famously unlikeable, and the narrator of her celebrated second novel is no exception. On a cocktail of real and invented drugs, “Neuroproxin, Maxiphenphen, Valdignore, Silencior, Seconol, Nembutal, Valium, Librium, Placydil, Noctec, Miltown,” she induces a yearlong chemical hibernation which slowly becomes a work of performance art. If she is awful, she is also, Moshfegh seems to joke, the perfect woman vis-à-vis our damaged culture: thin, blond, beautiful, and compulsively passive—indeed, usually unconscious.

How to Murder Your Life by Cat Marnell

Marnell is the paradigmatic millennial hot mess of the type that, I suspect, helped to inform Cline and Moshfegh’s protagonists. Her viral 2017 memoir begins in her Ritalin-fueled years at a New England prep school and follows her to New York in the early aughts, where her nights are wild, her days obsessive, an amphetamine-fueled rise through the ranks of the era’s favorite (defunct) fashion publications. Incidentally, as those who enjoy a bit of celeb gossip might know, Marnell is sober and working on a novel; it is into this project that she seems, these days, to be pouring all her dated glamor: “I type with my now hands to dress my vivacious ‘fictional’ character in crop tops, broken Tina Chow earrings, Jurassic Park ‘Clever Girl’ g-strings, and ab glitter before sending her out on the town to do things like hook up with the Florida-based white rapper Skiff-Skaff at a Times Square hotel,” she wrote in a recent Substack post. Meanwhile, “when I, Cat, finish writing every weekday, I . . . grab my Trader Joe’s tote bag before I leave the house; no one sees me except the stoners at the Third Avenue UPS Store when I make Amazon returns.”

Normal Girl by Molly Jong-Fast

If fast-paced rich-white-girl turn-of-the-millennium trash is what you crave, let Molly Jong-Fast be your Paris Hilton to Cat Marnell’s Nicole Richie. Though Jong-Fast’s semi-autobiographical novel came out in 2001, sixteen earlier than Marnell’s memoir, she is only four years older than Marnell, and their books take place during the same time period, more or less, in the same well-heeled, Sex and the City-era New York. Indeed, Jong-Fast—who is the daughter of novelist Erica Jong and author Jonathan Fast, and the granddaughter of writer Howard Fast—has said that Normal Girl was a kind of fictional response to the “memoir craze” of the time. The difference is that Jong-Fast’s novel is explicit social satire, while until recently Marnell lived and breathed the character of herself she also wrote.

The Recovering by Leslie Jamison

I found Leslie Jamison’s hybrid, journalistic memoir The Recovering immensely meaningful in early sobriety. Gary Greenberg wrote of Jamison in his 2018 review of The Recovering in The New Yorker, “We perhaps have no writer better on the subject of psychic suffering and its consolations.” In addition to tracing the contours of Jamison’s own early recovery, this book tells the story of many other addicts, from the entirely anonymous to the famous and often literary (Carver, Cheever, Denis Johnson, John Berryman, Elizabeth Bishop). In so doing, her book explodes the genre of the navel-gazing addiction narrative from solo aria into a multitudinous chorus.

The post 9 Books About Chaotic White Girls Getting High appeared first on Electric Literature.