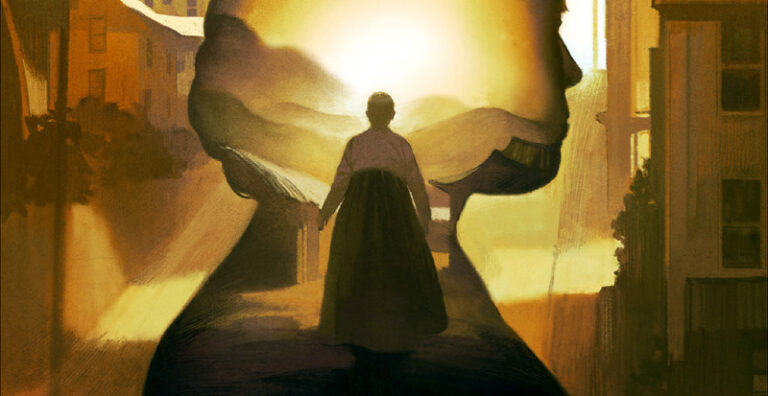

A Classic Chronicle of Korean America: On Kim Ronyoung’s Clay Walls

Clay Walls is a truly pioneering work. Though works by Korean immigrants and those born and raised in America like Kim Ronyoung were written before Clay Walls, Younghill Kang’s and Richard Kim’s books, for example, Kim’s novel is unique not only in being the first to be written by a Korean American woman but also in exploring the intergenerational Korean American women’s experience both here in the United States and abroad in Korea.

This is important not just historically but also aesthetically. Its narrative form ties together issues of racism in America, pan-racial and pan-ethnic references (LA Black and Japanese American communities, respectively, to name a few), colonization (Japan’s colonization of Korea, 1910–1945), issues of class in Korea and America, and Korean American life across urban and rural locales in the United States.

Clay Walls was published at the time of a “multicultural” publishing scene in the 1980s (published in 1987, by the Permanent Press), an era marked by a pattern of publishing more nonfiction (versus fiction) by Asian Americans and written by Kim Ronyoung, a self-taught creative writer who, despite illness, saw the publication of her novel before passing away from cancer. The near impossibility of Clay Walls being written is implied by the protagonist Haesu’s daughter, Faye, who shares in part three, “I’m not a real bookworm. It’s just a way for me to see how other people live. I haven’t found a book yet written about the people I know.” With this novel, Kim Ronyoung sought to fill that void.

Clay Walls serves to fully contextualize and validate one’s sense of home and homeland, and the possibility of multiple homes and homelands.

The novel is divided into three parts and named after Haesu, her husband, Chun, and their daughter, Faye. The continuous chapters that run across the three parts model the interconnectedness and the differences between the generations, genders, and culturally located spaces of each character within the spectrum of Korean America, though the characters and the narrators of each part are at seemingly insurmountable odds with one another. Part one begins with Haesu, a yangban, originally part of the aristocratic, educated class of Koreans, cleaning a toilet in Los Angeles, accosted by her employer who criticizes her for missing a spot. Haesu reveals she is married to Chun, whom she refers to as a sangnom, a person from the uneducated working class, and that they immigrated to the United States in 1920.

Besides the novel noting that hardly anyone in the United States knew where Korea was or knew Koreans as a people distinct from those from Japan, China, or the Philippines, the year 1920 signifies the March 1, 1919, Declaration of Korean Independence from Japan and its aftermath. First read in Seoul, this historic statement sparked a national movement with more than fifteen hundred demonstrations and two million participants. Japanese authorities warned that participation in the movement would result in severe punishment. More than seven thousand Koreans were killed, fifteen thousand wounded, and forty-six thousand arrested. This dangerous, national instability provides both the context and the foreshadowing of the difficulties in their own marriage both in Korea and America.

Though belonging to differing traditional Korean class levels, this cultural structure is unseated by the growing international influences of Japan and America, leading to a quickly arranged marriage with an international twist, and their arduous journey to America. Once in Los Angeles, issues of nationality, race, class, and gender, along with the stress of raising three young children while navigating life as newcomers, test Haesu, her marriage, and the family to their limits and beyond. Her marital union and abuses are symbolized by Korea’s own unity and well-being, suffering under colonial abuses, one country threatening to become two independent entities with the ever-increasing influence of foreign countries, along with their racialized reception in America. Yet even through, and because of, these contexts, Haesu still hopes to return “home” someday to a land of clay-walled homes.

Part two is told through the lens of Haesu’s husband. Chun is mistaken for someone involved in the Korean independence movement and receives help from an American missionary to marry Haesu and leave Korea for the United States. The novel addresses culturally arranged marriages (and who has the privilege of arranging them), the work of missionaries, the transnational interactions of Korea, Japan, and America, and the intersections of all these phenomena. Unlike Haesu, and given his farming and working-class experiences, Chun takes on menial labor in Los Angeles, saving enough money to buy a growing produce business.

Tragically, his gambling habits also grow with the demise of his business after losing US military contracts for his produce. In America, Chun’s life, his combative marriage to Haesu, and strained family dynamics are contextualized by the many historic layers globally and in the United States. Their own differences of gender and social structures, as Chun roams from job to job, place to place, California to Nevada, are caught in a perpetual cycle of overwhelming social forces too large to overcome, as Haesu and the growing children attempt at all costs to forge a better way forward on their own.

Part three is told from the viewpoint of Faye, the sole daughter of the family. Here the novel explores her friendship with other Korean Americans and their collective dating scene, but also within the context of her African American and Japanese American peers. Her exploration and growth mirror those of her mother, as Haesu now sews neckties to keep the family afloat. Noting the difficulties of second-generation Korean Americans, Haesu says, “It’s hard to be Korean living in the United States. Especially for you children. For me, it’s not so hard. I know I’m one hundred percent Korean,” to which Faye states, “Love swelled in my heart for Momma,” bringing to the fore questions of these characters’ “home” and the accompanying emotions, particularly for Faye.

The sense of Korean nationalism remains strong, ironically fueling their arduous assimilation into the United States and their pursuit of the American dream—through hard work, sacrifice, and dutifulness—all for one’s children, expecting them to do the same. The ideas of homeland and home are part of Haesu’s inner hope of returning to Korea on land they had bought. Haesu states, “My land in Qwaksan is gone,” to which Faye explains, “Qwaksan was gone and there was no money to show for it. The land was Momma’s only holding in her homeland and it had been taken away from her; her only holding in the world… She had hung onto Qwaksan as long as she could. I wanted to cry.” Thus, the dream of returning “home” is no longer possible, as they are in Los Angeles presenting the question of the constructions of one’s cultural identity, particularly one’s national identity. Faye continues, “Gosh, Momma, being one hundred percent Korean isn’t easy.”

Rather than capitulate to the common assumption that all Korean immigrants and Korean Americans perceive Korea to be one’s home, or America for that matter, Clay Walls serves to fully contextualize and validate one’s sense of home and homeland, and the possibility of multiple homes and homelands, cohered through a singular national identity, a transnational Korean American identity, clearing and affirming a space that neither yields to one’s foreignness or the expectations of full American assimilation. Such is the dilemma of the place and space of the Korean American experience.

*

In the early 2000s, fully intent on doing my doctoral dissertation on the literature of Japanese American incarceration at the University of Washington (UW), this Chicago-born child of Korean immigrants’ lifelong dream had finally come true: to study at UW with so many veteran and upcoming scholars and writers, principally Sam Solberg, Stephen Sumida, and Shawn Wong, and to live and reside in Seattle, a historic home to the Japanese American and Asian American communities.

This book has traveled not only the world, but worlds. The novel is a culture bearer of community.

As exciting as it was, I felt the need to scratch an itch of another long-held curiosity: Was there even such a thing as Korean American literature? I asked Professor Solberg if I could do an independent study. He patiently and graciously showed me name after name of Korean American writers, the growing scholarship on them forming in spurts. It was as if the scales fell from my eyes, and I began tracking every creative writer, their work, essays, and growing volumes of work, regarding Korean America.

On one afternoon, I read one of those writers and their work, and I began to weep inconsolably over the arduous and multilayered conundrum of Korean migrants to Hawaii, then the West Coast during Korea’s colonial period—and also over my ignorance. I had never read or heard of any of this. When I asked Professor Solberg if there was one author I could commit to researching, he said, “Kim Ronyoung, Gloria Hahn.” “Where is she and her work?” I asked. He replied, “She’s passed away now, and her work is in Los Angeles at a university library.”

I began hunting for her work, first at the University of California, Los Angeles, and ultimately found Clay Walls at the University of Southern California’s East Asian Library, along with the rest of her creative work, through the assistance of the then head, Dr. Kenneth Klein. From there, Dr. Klein connected me with Kim’s daughter, Dr. Melanie Hahn. And from there, I contacted places to republish Clay Walls. A chance meeting with Floyd Cheung led to his introduction to Elda Rotor about Penguin Classics and their focus on Asian American literature. I finished this essay in the LA metro area, where my father passed away nearly seven years ago, my parents having immigrated to the United States in 1972.

My mother’s family is here in the LA area, in Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco, Boston, Rochester, Florida, and Korea. My father’s family is likewise spread out, currently in Washington, DC, Orlando, China, and Korea. They have resided in urban, rural, and suburban places domestically and globally. My own family of five has lived in downstate Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Washington State, and the Chicago area (currently).

This book has traveled not only the world, but worlds. The novel is a culture bearer of community. Without which, I simply shudder, it would be the lesser for it. We all would be.

Kim Ronyoung remarked, “A whole generation of Korean immigrants and their American-born children could have lived and died in the United States without anyone knowing they had been here. I could not let that happen.”

Thank you, Faye, Haesu, and Chun. Thank you to the Fayes, Haesus, and Chuns of this world.

__________________________________

From Clay Walls by Kim Ronyoung. Published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Introduction © 2024 by David S. Cho.