Alexander the Great, Ancient Gay Icon

“Such men [who have sex with men] are sick because of nurture.”

Aristotle, Nicomachaean Ethics

*

Plato died in 348 BCE, a decade before the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BCE) when Athens and her allies were soundly defeated by Philip II of Macedon. Two years later, Philip himself was assassinated and the fledgling Macedonian empire was left to Alexander, his heir. Alexander of Macedon, later Alexander the Great, took advantage of Philip’s enrichment of Macedon and defeat of the Greek city-states, as well as the weak position of Persia in the East. He conquered Persia, marched down into Egypt and may even have reached as far east as modern-day Pakistan. With Alexander came what ancient historians call the Hellenistic period, when Greek philosophy and money flooded the Mediterranean and Asia in the wake of Alexander’s unstoppable armies.

Alexander the Great, from his teenage years, was famously handsome. He had beautiful hair, was lean and muscular, and all about him—according to one source—was a pleasant scent which made men and women all around him swoon with desire. It was said, however, that the Athenian politician Demosthenes belittled Alexander the Great in private, calling him a “pais.” The term “boy,” as we have seen, is often used for gay lovers in the ancient world. As well as describing Alexander as a “boy,” Demosthenes also referred to Alexander as “Margites,” the protagonist of an ancient burlesque poem, meaning “lustful man.” It is far from certain, but Demosthenes’ private references to Alexander imply that this most extraordinary general was a lascivious queer.

As Alexander grew older, he became more and more interested in sex and relationships with men.

At the court of his father Philip II, Alexander received the very best education that anybody in the ancient world could ask for. Philip sent for none other than Aristotle—an erstwhile pupil of Plato and one of the world’s greatest thinkers—to come to Mieza (the shrine of the nymphs in Macedon) when Alexander was still a teenager. Here, Alexander and Aristotle would sit in the garden, and Alexander was schooled not just in military strategy and political theory, but in matters that are far more mysterious.

We are told by Plutarch that Aristotle sought to impart on his young charge the secret mysteries of acroamatic and epoptic reasoning. We do not know exactly what this involved. It seems likely that in that garden, Alexander was taught advanced rhetoric and the power to subdue his opponents not by the sword, but with the word. His teacher was a master of this art: we are told that Plato refused to teach the subject at his Academy, delegating the task to Aristotle. Alexander adored literature of all sorts, and devoured Aristotle’s very own edition of Homer’s Iliad. According to legend, he slept with this revised edition under a pillow next to a knife with which to dispose of any nighttime assassins. Alexander also shared Aristotle’s fascination with medicine and the healing arts.

One text attributed to Aristotle betrays a fervent dislike of camp, gay men. Though we cannot be certain who wrote it, the text lays bare the worsening attitudes to queer and camp individuals in the Hellenistic period of Greek history.

The sign of the kinaidos (a man who enjoys sex with men) is a weepy eye, and a knocking together of the knees. The head is held to the right on the shoulder. The hands are turned upside down and move freely through the air. There are glances of the eyes, like those of Dionysius the Sophist.

Aristotle (or perhaps one of his disciples) attempts to diagnose what a gay man looks like and how he behaves. By this time, a prevailing idea in philosophy claimed that how a person looked betrayed information about their character and inner behavior. The lax hand gestures and incline of the head were taken to be the signs of an evil person. This is the beginning of a long tradition of the characterization of camp people as sinister.

In another text, which we are sure was written by Aristotle, he describes men who are by nature homosexual as “sick” and goes further than any other ancient commentators in diagnosing a new cause of same-sex desire. Aristotle argues that while some men desire other men because it’s their nature, in other cases, it arises from nurture. The latter is the case—for example—for those among boys who were raped. When nature is the cause, no one can say these men lack self-control, just as one would not say it of women who have sex. According to the same logic, it can be said that some men are sick by nurture.

Aristotle’s claim is still with us centuries later. Either gay people are sick or they are victims, evangelicals tell us. The fact that Aristotle uses the medical language of sickness and disease to discuss homosexuality shows just how far homophobia had spread. However, he does note that some forms of same-sex desire have nothing to do with a lack of self-control. This idea was not completely new. Xenophon talked some decades before Aristotle about how some men may have a natural tropos (“orientation”) towards other men. As Alexander grew older, he became more and more interested in sex and relationships with men. He grew estranged from Aristotle and turned to drink. Despite all his power, it’s said he became deeply ashamed in later life. In his youth, however, the ancient historian Plutarch tells us, Alexander was a model of self-restraint. He never had sex with women until he married with the sole exception of a woman called Barsine, although he would go on to have many affairs with women and wed multiple wives. Even when he captured many cities, he did not rape the women he captured which was apparently rare enough to be worthy of comment. It is said of the Persian women he captured that he admired their stature, but passed them with all the interest of a man looking at statues.

Alexander, or at least the Alexander that Plutarch conveys, spent the early part of his life demonstrating his extraordinary self-control. He was sitting at his desk on campaign, perusing various tightly bound letters that were brought to him and scribbling careful responses, when a messenger arrived and Alexander bid him come forward. It was a letter from Philoxenus, who was probably (though we are not certain) Alexander’s commander of the seas of Greece and Asia Minor. The letter contained various details of campaigns and attempts to subdue rebellious seamen. It was only when Alexander reached the end of the letter that things began to get interesting. There was a little postscript from Philoxenus that should Alexander be interested, a man named Theodorus of Tarentum was very eager to sell him “two boys of surpassing beauty.” Alexander replied. He commanded Philoxenus to sentence Theodorus to a horrific death; the instruction had a melodramatic flourish: “to dispatch him into complete destruction.” Clearly, this offer touched a nerve.

The young Alexander, at least as presented by Plutarch, went out of his way to show his complete disinterest in all sex. Plutarch tells us, “Sleep and sex made him aware he was mortal, since pleasure and tiredness originate from the same weakness of nature.” It was said that when exotic fruits, fish and food were brought to him, Alexander gave them to his companions instead. This habit, however, seems to have eroded as life went on; towards the end of his life, Alexander is reported to have spent as much as 10,000 drachmas on a single meal. It seems that the fruits of self-control appealed less to the most powerful man who had ever lived. One imagines he wondered what the point had been in conquering the known world, if he wasn’t allowed a few indulgences.

*

While his father had subdued Greece, Alexander set about conquering Asia. It’s true that the old superpowers of Egypt and Persia were waning in their influence, but there can be no doubt about Alexander’s extraordinary gift for military command and his charismatic ability to woo the inhabitants of every country he came to.

There were other loves in Alexander’s life, but none who meant so much to him as Hephaestion.

Having marched his armies into Balochistan, Alexander stopped to rest in Gedrosia where, one evening, he watched a play in the theatre. As the aulos players emerged on the stage, Alexander took his seat in marble at the very front of the audience. The king looked on expectantly at the stage, at its exquisitely painted back-drop, depicting the wild, untameable sea of Troy. A young man hurried into the seat directly next to Alexander. Alexander leaned in to kiss him, and the entire crowd cheered and applauded. The lover’s name was Bagoas, and he was far from the only man Alexander ever kissed. The most famous of his lovers, a man Alexander had known since he was a young teenager under the tutelage of Aristotle, was Hephaestion.

When Alexander took the ancient and hallowed city of Troy, his army set up camp. In the early evening, the waning sun gilded that fabled grassy plain where Achilles and Hector struggled and died. Alexander and Hephaestion, accompanied by a small procession, set out on foot for a small tomb outside the ancient citadel. They knelt before the tomb, placing their interlocked hands upon it. It was believed to be the burial ground of the warriors Achilles and Patroclus, the two great lovers of the Trojan War. Alexander placed a crown of flowers on Achilles’ side of the tomb, and Hephaestion did the same on Patroclus’.

Modern historians are often very reticent to claim Alexander and Hephaestion had sex. Personally, I cannot imagine a world in which they did not. Nor apparently, could ancient historians. Curtius, writing about Alexander, explains that he was possessed of “restraint in unrestrained desires, an indulgence of desire within limits.” This implies Alexander had a reputation for a highly selective, careful attitude to sex. With those he loved, sex was fine; but, as we know, he was enraged by the idea that he would ever pay for sex with boy-slaves. As his tutor Aristotle had pointed out, some men are by nature queer, and it seems Alexander was one of them. Hephaestion was also the same age as Alexander, defying the age-unequal model of same-sex relationships which has long been assumed by classicists to have been the only model of Greek homosexuality.

It was said that Hephaestion became ill at Ecbatana in modern-day Iran. A doctor called Glaucias attended urgently to him and reports were sent to Alexander as often as there were developments, but nothing could be done. Eventually, after many hours, Glaucias knelt before Alexander and told him that his beloved Hephaestion, with whom he had spent his entire adult life and in whom he had trusted command of his armies, was dead.

Alexander, said to be a great healer himself, commanded Glaucias be hanged at the gates of Ecbatana for his failure. He then turned to his engineers and ordered that they strip the city of its defenses. He sent a messenger to a priest in Egypt, commanding him to deify Hephaestion.

Outside Ecbatana, an enormous pyre (said to be over 250 feet tall) was constructed. Hephaestion’s body was placed at the top, surveying the city where he had died. Alexander loaded between 10,000 and 12,000 talents of gold on the pyre, so that it shone in the setting sun. As the red and orange flames consumed the pyre, people for miles around must have seen the smoke rising into the sky. Alexander was inconsolable.

There were other loves in Alexander’s life, but none who meant so much to him as Hephaestion.

__________________________________

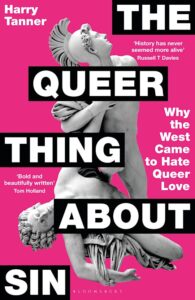

Excerpted from The Queer Thing About Sin: Why the West Came to Hate Queer Love by Harry Tanner, run with permission of the author, courtesy of Bloomsbury Continuum, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Copyright © 2026 by Harry Tanner.