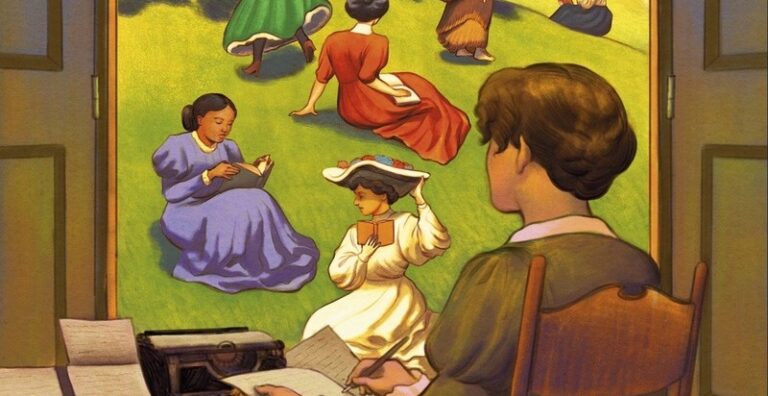

An Integral Part of the Story: A Short History of Short Fiction by American Women

Women writers from 1830 to 1926 turned to the short story for many reasons. In 1830, the short story was a relatively new genre and the first genre that we might consider to have been born in the United States. By 1926, it was a highly popular form that could be found in periodicals, anthologies, and collections by individual authors all over the world.

Most literary historians date the emergence of the short story to the tales that appeared in Washington Irving’s The Sketch Book, which was published in installments between 1819 and 1820 and included the story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Edgar Allan Poe, one of the genre’s earliest theorists, surmised that the strength of short stories was to be found in what he called their “totality”—a singular purpose and plot that carry the reader propulsively forward until the ending’s final blow. For this reason, short stories also offered an ideal format for using fiction to make an urgent sociopolitical point.

Short fiction was more likely to reach readers while escaping the notice of censorious reviewers and commentators. In the preface to a collection of ghost stories written between 1902 and 1937, Edith Wharton reflected that “most purveyors of fiction will agree with me that the readers who pour out on the author of the published book such floods of interrogatory ink pay little heed to the isolated tale in a magazine.” The downside of this equation was that, for the first half of the nineteenth century, short stories were not highly profitable endeavors for writers.

American women have played a significant role in the creation of an American culture of letters for as long as that role has been minimized.

As the periodical market expanded in the second half of the century, however, writers could more easily sell one‑off tales to editors, tiding themselves over financially while they labored at more lucrative long‑form projects. This was especially appealing to female writers, who often had both less time and less money than their male counterparts, as short stories could be produced and read within the disconnected intervals of free time that made up most women’s lives. In 1899, the writer Kate Chopin, who was a single mother to six children, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

When do I write? I am greatly tempted here to use slang and reply “any old time,” bet that would lend a tone of levity to this bit of confidence, whose seriousness I want to keep intact if possible. So I shall say I write in the morning, when not too strongly drawn to struggle with the intricacies of a pattern, and in the afternoon, if the temptation to try a new furniture polish on an old table leg is not too powerful to be denied; sometimes at night, though as I grow older I am more and more inclined to believe that night was made for sleep.

Chopin’s claim that her writing fits in at “any old time” like a hobby rather than an occupation should be taken both seriously and with a grain of salt. Chopin was a dedicated writer who worked at a constant pace and recorded the sales of her stories in a ledger, keeping tabs on what themes and formats won her the highest prices. But she was also a single mother and a woman living at the end of the nineteenth century, when the public nature of professional writing was still a somewhat dicey prospect for female writers who wanted to maintain their esteem in social circles.

So, the paradoxical nature of Chopin’s statement and status as an artist (both serious and not serious) in many ways mirrors the central paradox of the emergence of female authorship in the United States: American women have played a significant role in the creation of an American culture of letters for as long as that role has been minimized. In large part this is because writing is a profession, and while women needed no encouragement to take up their pens, the United States has long had an aversion to female professionalism.

In some ways, the idea of an “emergence” of female authorship in the United States makes no sense. It was never the case that women were barred from authorship or relegated to the sidelines of the creation of an American literature. It is simply that their contributions have been so insistently overlooked, discredited, or left out of sweeping literary historical narratives when, in fact, women have been at the forefront of print culture in the United States since its beginnings. The 1650 collection of poetry The Tenth Muse, Lately Sprung Up in America by Anne Bradstreet was one of the earliest publications distributed in colonial America. Years later, Bradstreet publicly claimed to have had the work published against her will in a poem, “The Author to her Book,” which includes the self-deprecating lines, “Thou ill‑form’d offspring of my feeble brain, / Who after birth didst by my side remain, / Till snatched from thence by friends, less wise then true / Who thee abroad, expos’d to publick view.”

Ostensibly, Bradstreet denies any serious intention of trying to become a published author. Such a masculine aspiration, especially in her historical moment, would subject a woman to scorn and ostracism. Even two hundred years later, when the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe had become the most famous woman in America for writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book that nearly every literate American read, she claimed to not have written it at all, stating instead that God spoke through her pen. Stowe would also refuse to read publicly, preferring to observe popular prohibitions against female orators by sitting silently on stage while her husband, Calvin, read her words for her.

Despite these pretenses toward modesty and disinterestedness, American women would continue to write prolifically and with a purpose. Phillis Wheatley, a young woman kidnapped from Gambia as a child and brought to Boston to work as an enslaved domestic laborer, published the first volume of poetry by an African American in 1773. In it, she condemned the Atlantic slave trade and subtly criticized the racist hypocrisy of abolitionist Bostonians. One of the first bestsellers to be printed in the United States was the 1797 epistolary novel The Coquette by Hannah Webster Foster. Published anonymously, it was a fictionalized account of a woman who died at a roadside tavern after giving birth to a child out of wedlock. Foster’s work drew attention to the double standard of sexual propriety that destroyed so many women’s lives in her time, setting a precedent for women writers who transcended confinement to the domestic sphere by voicing their opinions in print.

Many nineteenth‑century women who became writers had to put virtue aside precisely because they had no husband or male relatives who could support them financially, and these were inevitably the writers whose works were the most harshly critical of the laws and social practices that still so dramatically restricted women’s ability to achieve independence through work. The writer Sara Payson Willis Parton, who published as Fanny Fern (the name itself was a parody of the frilly feminine noms de plume that populated the kinds of popular periodicals Sedgwick satirized), also found herself unable to support her family as a young widow.

She remarried hastily under familial pressure and her family withdrew financial support altogether when she left her abusive second husband. Motivated by equal measures of financial desperation and literary talent, Fanny Fern’s 1854 novel, Ruth Hall, was a thinly veiled autobiographical account of her desertion and her rise to fame as a popular columnist. Nathaniel Hawthorne enjoyed the novel, writing to his editor that “the woman writes as if the devil was in her.” In an article in the New York Ledger, Fern succinctly stated the nature of that devil:

There are few people who speak approbatively of a woman who has a smart business talent or capability. No matter how isolated or destitute her condition, the majority would consider it more “feminine” would she unobtrusively gather up her thimble, and, retiring into some out‑of‑the‑way place, gradually scoop out her coffin with it, than to develop that smart turn for business which would lift her at once out of her troubles; and which, in a man so situated, would be applauded as exceedingly praiseworthy.

The most radical thing about the novel Ruth Hall may be that it ends in financial independence—not marriage—as the bringer of safety and salvation.

For many years, our concept of American Women’s literature in this period was shaped by a small cadre of wealthy, white women from the Northeast like Sarah Orne Jewett, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Edith Wharton. There are many reasons for this, but primary among them is the fact that such women were more likely to have the education, resources, free time, and social connections that made publication a possibility. Women of color who published in the United States in this period both overcame extraordinary barriers and leveraged extraordinary advantages to do so.

While many poor and working-class African American storytellers continued to create and circulate stories within an oral literary tradition, the African American women who published fiction during this period in volumes and periodicals most often came from families that had been free for more than one generation and who had financial resources and access to education. The genres that would allow such writers to place their work in the mainstream periodicals of the day belonged to a written tradition that typically had to be learned within the context of formal schooling. Likewise, while indigenous oral traditions allowed tribal communities to record their own cultures and histories through storykeepers, Native American women who published during this time did so by having learned the conventions of white educational systems.

Writers who found themselves at the intersection of more than one cultural and literary tradition had a careful line to walk when writing as representatives of a nondominant group for predominantly white audiences. María Cristina Mena was the daughter of a Spanish mother and a Mexican father whose business profited under the corrupt rule of Mexican President Porfirio Díaz. For her education, Mena was sent to a convent school for the daughters of the Mexican elite and then to an English boarding school. Her first published stories were written and appeared while she was living in New York City, where she was sent amidst rising political tensions in Mexico. She was considered a local color writer, and scholars today have debated how to position the complex attitudes towards race that appear in her fiction.

By turning to them now, we assert the value of learning the past as a part of our own story. It is in this way that these writers can still guide us—by showing us where we came from.

Like Mena, Sui Sin Far was a mixed-race writer who made significant inroads in the representation of non-white protagonists in the popular fiction of the period. Born Edith Maude Eaton in England in 1865, she was the daughter of an English merchant father and Chinese mother who met in Shanghai. “Mrs. Spring Fragrance,” Sui Sin Far’s most well-known story, is set in the thriving Chinatowns of San Francisco and Seattle. Her protagonist enjoys the relative freedoms of the women in her urban American context but remains rooted in traditional Chinese cultural values.

Along with her sister, Winnifred Eaton, Sui Sin Far was one of the first Asian American writers to represent Asian American life. In her work, she at times relied on stereotyped depictions that present-day readers may identify with the orientalism of white writers during her period. Her writing was, however, deeply critical of US anti-Chinese policy as well as, as the literary scholar Mary Chapman has shown, the exclusionary whiteness of the women’s suffrage movement during her lifetime.

In the early twenty-first century, when feminist movements are thankfully becoming more intersectional and concerned with how the various identities female-identified people hold contribute to their unique perspectives as well as their privilege and oppression, it may be tempting to see the increasingly diverse canon of American women writers as representative of American women’s lives. But our published short stories can offer only a more complete survey of the period’s literature. Then, as now, unequal access to education, healthcare, and childcare severely delimited whose works of creative expression could be professionalized and who would be exposed to the liberatory frameworks they may need in order to find their voice in the first place.

Students and scholars of literature alike tend to privilege writers who they can identify as having been ahead of their time and the recovery of American women writers initially proceeded by first attending to the writers whose views looked a little bit more like late twentieth-century ideas of feminism. Praising a writer for being ahead of their time is, after all, the same as saying we like them because they are more like us.

But one of the most important things reading can do for us is to teach us more about the thoughts, feelings, and circumstances of those who are not like us. This can mean reading texts written in our own time by writers whose identities are very different from our own. But it can also mean looking to literature to give us a more multifaceted understanding of the past. Most great writers in the history of literature are probably better described as “of” rather than “ahead” of their times. But this only means that in reading their words, we can understand the past in a more nuanced way, which, in turn, gives us insight into our own shortcomings.

How many of us, truly, would be considered ahead of our time if our thoughts were to be read a hundred and fifty years from now? It is impossible to say from our present vantage point if the people of the future would be horrified by how we understand race, gender, the environment, or wage labor. We cannot look to our historical writers, who are similarly embedded in the prejudices and specific material conditions of their own moment, to solve the problems we face today. But they are our ancestors, all, and they have much to offer us beyond solutions.

Such fiction is the work of women who turned to literature themselves to try to better understand their own world and their role within it, and by turning to them now, we assert the value of learning the past as a part of our own story. It is in this way that these writers can still guide us—by showing us where we came from.

__________________________________

From Twelve Stories by American Women, edited by Arielle Zibrak, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Introduction copyright (C) 2025 by Arielle Zibrak.