“Are We Lost?” How Ancient Cultures Across the Globe Found Their Way Around

Humans do not have an innate neurological toolbox like animals, but they do possess language. The configuration and language of the four directions is common to many—though not all—cultures. They probably even pre-dated astronomical observations of the Sun’s movements and the stars and were first inspired by the ‘egocentric coordinates’ of the human body. Our most basic corporeal orientations are fourfold: front and back, left and right. In many ancient languages ‘front’ and ‘back’ are synonymous with east and west, while ‘left’ and ‘right’ are often equivalent to north and south. So in Hebrew, east—qedem or mizrach—also means ‘forward’ or ‘front’, while ‘west’—achor—is a synonym for ‘behind.’ In Arabic, north is al-shamāl (‘left’), south is al-janūb (‘right’). For both these languages the universe, in which sacred and ritual beliefs are based on facing east, mirrors the body.

Other cultures use the body’s position to interpret directions in very different ways. Many of the terms used are deictic, in other words they are dependent on their physical context and can shift according to the speaker’s point of view (examples of deictic terms about space include ‘here’, ‘there’ and ‘across’). In ancient Chinese, the pictograph for north, 北, or běi, represents two people back to back, the dark and cold north synonymous with the ‘back’ of the body, whose ‘front’ looks southwards (nán), in the direction of light and warmth. In Japanese, north is kita—‘behind’ or ‘afterwards’—with minima meaning south, a feminine version of ‘to face.’

Humans do not have an innate neurological toolbox like animals, but they do possess language.

Many south-eastern African Bantu languages also use corporeal references to distinguish between the four cardinal directions. In Kihehe, the language of the Hehe people of Tanzania, north is kumitwe, which derives from mitwe, or ‘head’, and south is magulusiika, from magulu, meaning leg. Along similar lines, ancient rock art made by the Dogon people of Mali often depicted a personification of the ‘life of the world,’ or aduno kine, as a simple diagrammatic figure personifying the Dogon creation myth in which the deity Amma stretched an egg-shaped ball of clay in four directions with north at the top to create the world grasped in the god’s hands. Cave paintings show a figure with a torso and arms forming a cross that represents the four cardinal directions. The head is north, the legs south, the left arm east and the right west.

Dividing orientation into four directions emanating from the body is part of a larger symbolic fascination with ordering natural phenomena. In mathematics four is the smallest composite number (a number divisible by a number apart from one and itself). In geometry it is related to the cross and the square and their associations with totality and completeness. The Arabic numeral 4 originated in a simple cross which added the diagonal stroke that is now most familiar in Western numerals. Quadripartite symbolism has provided many cultures and religions with an organizing principle for the seasons, continents, winds, elements, ages of ‘man’, natural causes (according to Aristotle) and the four corners of the Earth.

The ancient Chinese dynasties divided their domains into four lands (si tu) and imagined the world formed by four seas. Each of the four cardinal directions were imagined as ‘intelligent creatures:’ the green dragon of the east; the crimson bird of the south; the white tiger of the west; and the black turtle of the north, each colored direction matching the hues of the soil in the corresponding Chinese regions. Buddhism believes in the four cardinal directions representing elements and cycles in life, moving from east (dawn) through south (noon and fire), west (dusk and autumn) and north (night and dissolution). Hinduism reveres the four Vedas (religious texts) and alongside Hindu mythology includes the Lokapāla, the four guardians of the cardinal directions: Indra (east), Yama (south), Varun˙a (west) and Kubera (north).

*

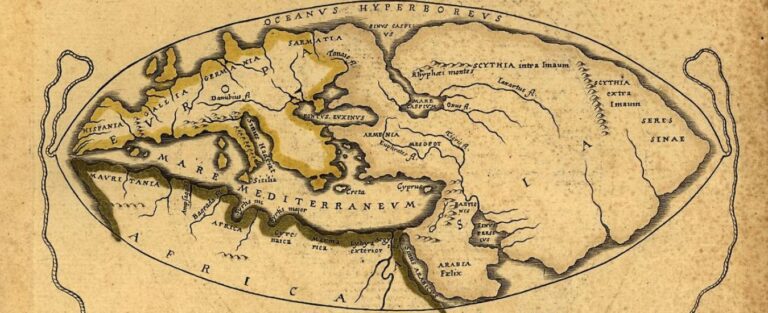

The earliest surviving record of the four cardinal directions was made during the first great Mesopotamian empire, the Akkadian dynasty (c. 2350–2150 BCE), whose ruler Naram-Sin (r. c. 2254–2218 BCE) is the first known to have adopted the title ‘King of the Four Corners of the World.’ Archaeological excavations undertaken in 1931 at Yorgan Tepe, south-west of Kirkuk in modern Iraq, unearthed hundreds of clay tablets containing Akkadian and Sumerian cuneiform inscriptions. One of the most significant of them measures just under seven by eight centimeters. It is a topographical map and is usually referred to as the ‘Gasur map.’ At its center is an agricultural estate, through which a river runs from top right to bottom left before branching off into two tributaries that flow into a larger body of water on the far left. The settlement sits in a valley with two mountain ranges running across the top and bottom of the map. The lake has recently been identified as Zrebar (or Zerivar) Lake in the Kurdistan province of western Iran. The inscriptions offer an account of the central agricultural estate, described as 300 hectares of “cultivated land.”

The Gasur map is the oldest known map to show and name cardinal directions. The damaged semi-circle top left is labelled IM-kur, ‘east;’ the one bottom left is inscribed IM-mar-tu, ‘west;’ and to the centre left IM-mir, ‘north.’ Presumably the missing section of the tablet’s right-hand side originally included the inscription IM-ulù, ‘south.’ Yet the naming here is not quite what it seems. The prefix ‘IM’ (‘tumu’) refers to winds—the map identifies four directions by meteorological experiences rather than astronomical observations. Other Mesopotamian texts describe four principal winds forming a diagonal cross, equivalent to the modern directions of north-west, north-east, south-east and south-west. These translate into the Akkadian terms on the Gasur map as IM-kur, a north-eastern ‘mountain’ wind, which blows in from the Zagros mountain range to the north-east of Mesopotamia; IM-mart-tu, a south-western ‘desert’ wind derived from the word Amurru, describing the nomadic Amorite people of Syria and Palestine west of the Euphrates, as well as the direction from which hot sand-storms blow; IM-mir, the most prevalent wind from the north, a regular, strong, yet dry wind that cools the land; and IM-ulù, a south-eastern ‘demon’ or ‘cloud’ wind that originates in the Persian Gulf, bringing unpredictable, gloomy and wet weather.

These cardinal directions referred to quadrants rather than points and derived from specific aspects of human and physical geography. For the farmers cultivating the land in Azala (modern-day Kurdistan) over 4,000 years ago, the four cardinal directions in terms of prevailing winds were not only a means of orientation: understanding wind direction and changeable climatic conditions was crucial for the cultivation of crops and could mean the difference between feast and famine. When the cuneiform text on the map is read from top to bottom, IM-mir, the direction from which the regular north-western winds blow, is the prime orientation.

On the Gasur map, IM-mir is established as a word with connotations of fertility, renewal, prosperity and temperance, in contrast to IM-ulù, which operates within Akkadian social conventions and language as a term evoking volatility, danger and the fear of outsiders. At this stage in history, the connotations of these two directions became embedded in the rhythms of sedentary, agricultural societies with little or no reference to travel or orientation, which were largely irrelevant to such communities. The words and connotations of cardinal directions that are spoken give shape and order to societies; they are part of an activity that anchors people within their physical world and makes sense of their surroundings.

The Mesopotamian combination of meteorological, geographical and ethnological words for the four directions and their various connotations find parallels, albeit in very different terms and under contrasting conditions, across the globe and in many languages throughout early recorded history. The prevalence of other directions, such as egocentric references—those from a subjective perspective like front/back, left/right—and allocentric examples—using landmarks or objects including rivers and mountains independent of a subject’s point of view—are greater in some languages. Indigenous cultures like that of the Guugu Yimithirr people in Queensland in Australia’s far north have an acute sense of cardinal directions but with little perception of egocentric coordinates. Instead they use a system of ‘absolute’ geographical orientation, referring to things and places as relative to the cardinal directions, rather than themselves. Rather than saying, “Please move to the left,” they would say, “Please move to the west,” and “Pass the salt, it’s to the north,” instead of “Pass the salt, it’s under your nose.” Some—usually societies sparsely populating small regions, such as the Yurok people of northern California—possess no terms for any of the four directions. Compass points are common to most societies, but they are not universal.

The etymologies of cardinal directions across different cultures reveal their speakers’ preoccupations with and rules for using each word within any given society. In Africa the language games within which each direction found expression were often defined through complex ethnological distinctions. The Zulu word for south is iningizimu, which translates as ‘many cannibals.’ Traditionally the sea lay directly south of the Zulu kingdom, the origin of cold winds and fog that hid malevolent spirits and man-eating monsters. Various south-east African languages also derive the names of cardinal directions from neighboring ethnic groups: the Setswana and Sesotho languages use bokane (north) to describe Nguni-speaking people to the north, while borwa (south) derives from the word for ‘Bushmen,’ or the Khoisan of southern Africa.

Ancient Mesoamerican cosmologies used cardinal directions to describe their gods and stories of Creation. The Mayans of northern central America understood east and west first, based on astronomical observations of the rising and setting Sun, before meanings associated with north and south. In Mayan belief, their solar god and creator, Itzamná, split into four deities called the Bacab (sometimes shown as jaguars) that held up the four corners of the world, each one representing a direction and a color. East (translated as ‘exit’—of the Sun emerging from the underworld) was associated with red and fire, and west (translated as ‘entrance’ of the Sun setting into the underworld) with black, symbolizing darkness and imminent night. North (often associated with white) and south (usually labelled yellow) were less demarcated as both directions and colors, and changed over time and across Mesoamerican languages and cultures.

The words and connotations of cardinal directions that are spoken give shape and order to societies.

What was strikingly different about Mayan and subsequent Mesoamerican cardinal directions from those of Mesopotamia and most other cultures was that they operated on three, not two axes. The Aztecs imagined the Earth as a horizontal disk divided by the dual east–west and north–south axes. At its center ran a third, vertical axis mundi. The result was a quincunx, a geometric pattern of five points arranged like a cross, effectively structuring the Aztec world picture according to five directions. In 1325 CE the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico City) was founded around the Templo Mayor, which symbolized the Aztec centre of the world, where the vertical and horizontal axes of the cardinal directions met, and the heavens, the Earth and the underworld came together.

Greek philosophy and science showed no interest in a fifth direction, nor color-coding the directions. Instead it inherited the Mesopotamian agricultural preoccupation with winds. Mythical personifications of the four directions as gods, or Anemoi, first appear in the ancient works of Homer (c. 800 BCE). His Iliad and Odyssey both mention four gods representing cardinal winds. Boreas, the north wind, is possibly an archaic variant of ‘mountains’ or ‘roaring;’ Notos, the south wind, derives from ‘moist;’ Eurus, the east wind, comes from the ‘brightness’ of sunrise; the western wind of Zephyrus stems from the ‘gloom’ of sunset.

In ancient Greece weather was assumed to emanate from Zeus, but his meteorology was fickle and unpredictable. Subsequent natural philosophy wanted to challenge the view that natural phenomena such as the weather lay in the hands of Zeus and other deities. As the rules of the game shifted so did the language of the four directions: astronomical observations began providing alternative names, including describing the north as Arctos, or ‘the bear,’ taken from the northern constellation of Ursa Major.

The earliest and most powerful case for the centrality of climate and directions in Greek life was made by Aristotle in Meteorology (c. 350 BCE). Taking as his subject “everything which happens naturally,” Aristotle described the Earth as a sphere sitting at the centre of the universe. Meteorology included the earliest known geometrical diagram to codify cardinal directions according to wind systems, showing the northern hemisphere with Greece at the centre. It shows eight principal winds, or twelve altogether including ‘half winds’ (Eurus is replaced with Apeliotes, the “heat of the sun”). This systematic codification of winds as coming from a specific direction was central to Aristotle’s ethnological approach to the Earth, which he divided into five climatic—klimata, meaning ‘slope’ or ‘incline’—zones. They were based partly on meteorological conditions, as Aristotle reasoned that the ‘incline’ of the Sun lessened the further north one travelled from the Equator, creating intemperate zones at the poles and the Equator, leaving just two habitable ‘temperate’ zones.

Greek agriculture and its growing maritime trade needed to anticipate the weather, as Aristotle’s disciple Theophrastus of Eresos (c. 371–287 BCE) knew. In his book On Winds (c. 300 BCE), he claimed that “what happens in the sky, in the air, on Earth and on the sea is due to the wind.” Timosthenes of Rhodes (fl. 270 BCE) went even further. His twelve wind directions each described different regions and people. This was a significant development in human geography that subsequently connected cardinal winds with geographical directions and cultures. Aparctias (north) was associated with Scythia, the Central Asian nomadic kingdom; Notus (south) with Ethiopia; Apeliotes (east) with Bactriana, covering most of Afghanistan; Zephyrus (west) with the Straits of Gibraltar, the westernmost limits of the classical world. Celtica, Iberia, India and others were also aligned with winds. As the preoccupations of Greek thinking embraced human geography and trade, so the words for each direction changed and the rules of their usage also shifted. This began a conflation of direction with identity that still persists today.

The Greeks even built a ‘Tower of Winds’ that still stands in Athens. Designed by the astronomer Andronicus of Cyrrhus around 100 BCE, each side of the octagonal tower shows deities facing one of eight principal directions: Boreas (north), Apeliotes (east), Notus (south), Zephyrus (west), as well as Kaikas (north-east), Eurus (south-east), Lips (south- west) and Skiron (north-west). Not only is the tower the first known weather station, it also functioned as one of the earliest known clock towers (horologion). Below each deity is a sundial; inside the tower are the remains of a water-clock, the beginnings of a long history in which the measurement of time is involved in understanding direction.

The Tower of the Winds stood in the Roman Agora (27–17 BCE), or meeting place, and the Romans gradually adopted the Greek terms for winds and introduced new Latin words. North came first, named borealis or septentrionalis, a reference to the ‘seven stars’ of Ursa Major. South was given several new terms, including australis (‘harsh’ or ‘sharp’) or meridionalis (from ‘midday’). West was occidentalis (‘falling’ or ‘passing away’) and east was orientalis (‘rising’ or ‘originating’) or subsolanus (literally ‘under the sun’). Nevertheless, the adaptation was messy and contradictory, with some Greek names being retained, competing Latin synonyms introduced and debates about the correct number of wind directions. The Roman architect Vitruvius even introduced a twenty-four-point wind ‘rose’ in his book On Architecture (c. 30–15 BCE). Vitruvius emphasized the importance of harmony, order and proportion in planning “the orientation of the streets and lanes according to the regions of the heavens” and the winds. The Greek ‘pneuma’ means air in motion, understood as breath—or wind. The outside air, or wind, we breathe—from whatever direction—is what keeps us alive. The character and quality of winds determined life and death.

In later societies the winds were central to personal orientation. For the Inuit people living in the Arctic regions of Greenland, Canada and Alaska, the primary tools for navigation were the winds and snowdrifts, elements of a very different environment to that of the Greeks. Winds were personified and gendered according to their temperament. The north-western Uangnaq is often regarded as the prevailing wind and considered female, due to its volatile nature: it can gust furiously then die away just as quickly. The ‘male’ south-easterly Nigiq blows in more steadily and is believed to ‘retaliate’ to its opposite, the Uangnaq. This gendered pair formed a cardinal axis, with Kanangnaq (north-east) and Akinnaq (south-west) completing the four Inuit cardinal directions.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Four Points of the Compass: The Unexpected History of Direction by Jerry Brotton. Copyright © 2024 by Jerry Brotton. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.