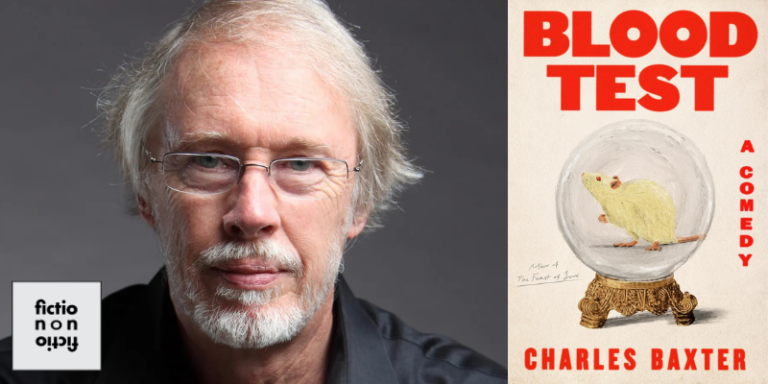

Charles Baxter on the Dangers of Knowing the Future

Acclaimed novelist Charles Baxter joins Fiction/Non/Fiction hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to discuss his recent novel Blood Test: A Comedy. Baxter talks about turning to humor in dark times, the burden of expectations, and writing a protagonist, Brock Hobson, who some readers love and others detest. He discusses how seeing websites and ads that predicted his likes and dislikes led to him inventing a fictional company, Geronomics, which predicts a certain future for Brock and is invested in that scenario playing out one way or another. Baxter also analyzes the craft of writing an antagonist who is a Trumper, but who is never explicitly identified as such. He reads from Blood Test.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/.

This podcast is produced by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: Thanks for joining us. Your main character—I’m going to resist mispronouncing his name, as certain people do in the novel every single time he’s referred to— Brock Hobson lives in Kingsborough, Ohio. He’s recently divorced. He has two kids, Joe and Lena. Beyond that, can you introduce him to our listeners?

Charles Baxter: Sure, he is a straight, middle-aged, white guy in the Midwest, but I think he’s interesting anyway, because, like a lot of people of that age, he feels that he’s fallen into a kind of rut. The shine has gone out of everything for him, and he’s at that point in his early middle age when he can’t remember what he did yesterday, because it’s the same thing that he’s done today. On top of that, he’s trying to hold his family together. He’s divorced, he has a son and a daughter, and he’s trying to hold everything together after his wife has left him. He’s gotten to the point where he needs, almost without knowing that he needs it, he needs a change. I think he’s a sort of ideal character for a novel, because he needs a change, and what the novel does is to bring him that change.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So, he describes himself as Mr. Predictable. I felt a lot of sympathy, he’s a very sympathetic character, because he thinks, ‘Everyone thinks they know me, and I want a little bit more excitement.’ Then he has this encounter with this company called Geronomics that predicts a future for him and it isn’t like what he would predict. It isn’t really what anyone would predict for him and everyone who hears this prediction is sort of like ‘oh no, you would never.’Much later, he quotes a former professor of his who says, “in myth, knowing the future is usually a catastrophe for the one who knows.”

I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how you invented Geronomics, and talk to us a little bit about your own thoughts on knowing the future. If you’ve ever had a moment when you felt predictive? I was at a reading for this book and someone asked you about Macbeth in relation to this idea.

CB: Yes, so, a couple of ways of approaching this question. The first is that, in order to talk about where this book got started, you have to remember how you were at the beginning of the pandemic. We were all cooped up. It was as if life had become diminished for us, I think everybody was suffering, and I thought, I don’t want to write another novel that makes people feel worse than they already do. I want to write a book that will be funny and lighter in some respects than the books that I had written prior to that. And it was around this time that I was going to various websites to buy things, and I noticed that a lot of these websites were telling me what they thought I would like and what I should buy, and I thought that was very interesting. And it was about the time that chatbot AIs were getting into the news, and I thought, ‘you know, it’s really only a matter of time before computers begin to predict our behavior and start selling us and monetizing our future.’

So I thought, now, what do I need in order to do that? Well, I thought, without knowing much of anything about genetics, that it would be a bit of an interesting leap if you were to send a blood test, if it were run through a computer and an algorithm, and the blood test was predictive and told you what you would be doing before you knew that you were going to do it. In answer to the second part of the question, I have taught Macbeth several times. Years ago, I taught Oedipus Rex, and had thought about the myth of Cassandra and the Old Testament prophets, and I thought, ‘well, yes, if you know the future, it’s not good news, it’s not good news.’ I don’t feel as if I’ve really known the future, but a lot of people think that they can foresee bad outcomes, and it’s why we have interventions.

WT: As a parent, there are times with my kids where I’m like, I think I know how this is going to go, but the important thing is not to say that.

CB: Yeah, they hate it. They hate it when you say that.

VVG: In the same way that Brock hates being told that. Everyone wants to have a little bit of mystery.

CB: Of course, and the more you lurch into middle age, the more you want some of the mystery. You don’t want to feel as if you figured everything out, that’s no fun.

Also, one of the things that I did in his characterization was I made him into a Christian. I’m not a Christian myself, but I thought it would be interesting to make him one. And I thought, ‘now, why am I doing this?’ And I was doing it because he wants to believe in rebirth. He wants to believe in renewal. He needs something to hold on to that will give him hope.

VVG: So, what was it like for you as a person who is not particularly religious to inhabit that point of view?

CB: Well, I grew up in it, so I remembered Sunday school classes, I remembered all those times. I know the Bible pretty well, and so I could draw on certain elements of the Gospels of the Old Testament. It wasn’t too large a leap, really, and I wanted to make it just part of his background that would intrude from time to time, which is why I had a few scenes in which he’s teaching Sunday school.

VVG: I kept thinking about the ways in which certain aspects of science are also schools of belief. As I was reading, I kept thinking of, like, RFK Jr, or all of the ways in which I’m so reason-oriented and so science-oriented, and that can be kind of, like, a fascism of, I don’t know. It has been something that I’ve thought about and worked on, that I don’t want to—just because I’m not a religious person doesn’t mean that it’s …. there are so many religious people in the world, I’m coexisting with those people, I respect those people—

WT: Fascism of reason? Was that the word that was kind of trying to climb out of your mouth there for a second?

VVG: No, not fascism of reason, but a self-righteousness, being like, ‘Well, I’m a scientific person, so I’m right.’ And there’s a way even that, like the far right, there’s a rhetoric of science that they’re using even when they’re not talking about science.

CB: Yeah, I think what we’re talking about is authority, and who can claim authority over whom and with what reason are they using it. I started to think about this because it seemed to me that young people, much younger than I am, people in their 20s and 30s, are taking the authority of computers, particularly AI, as a guide for them. I can say that one of the people who had come to one of my bookstore readings came up to me afterwards and said, “I just want you to know that I don’t think that your book is all that farfetched.” She said, “I have a relationship with a chat bot, with an AI.” And I asked, “what sort of relationship do you have?” And she said, “I ask it for advice.” She went on to say that she’s shy. She wasn’t sure that she should go to a bookstore reading. She asked the computer whether she should go and the computer said, “yes, you should.” Now, that’s a kind of authority that’s really interesting. That’s a kind of authority, and she’s handing over the responsibility for organizing her life to a machine. Yeah, and I was interested when I wrote this book on sort of carving out a little section of belief for free will in the face of what some machine is telling you you’re about to do.

*

Blood Test: A Comedy • Wonderlands: Essays on the Life of Literature • Gryphon • Burning Down the House: Essays on Fiction • There’s Something I Want You to Do • The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot • Shadow Play

Others:

Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 5 Episode 33: “The Politics of Craft: Charles Baxter on How His Essays on Writing Respond to a Changing World” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 4 Episode 6: “Hope on the Horizon: Charles Baxter and Mike Alberti on Despair and Renewal in Fiction” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 1 Episode 4: “We’re All Russian, Now” • Humboldt’s Gift by Saul Bellows • Oedipus Rex by Sophocles • Macbeth by Shakespeare