Chelkash by Maxim Gorky

III.

He awoke first, gazed anxiously around, immediately recovered his self-possession, and looked at the still sleeping Gabriel. He was sweetly snoring, and was smiling at something in his sleep with his childish, wholesome, sun-tanned face. Chelkash sighed, and climbed up the narrow rope ladder. Through the opening of the hold he caught sight of a leaden bit of sky. It was light, but grey and drear—autumnal in fact.

Chelkash returned in about a couple of hours. His face was cheerful, his moustaches were twirled neatly upwards, a good-natured, merry smile was on his lips. He was dressed in long strong boots, a short jacket, leather trousers, and walked with a jaunty air. His whole costume was the worse for wear, but strong, and fitted him well, making his figure broader, hiding his boniness, and giving him a military air.

“Hie! get up, blockhead!” bumping Gabriel with his foot.

The latter started up, and not recognising him for sleepiness, gazed upon him with dull and terrified eyes. Chelkash laughed.

“Why, who would have known you?” said Gabriel at last, with a broad grin; “you have become quite a swell.”

“Oh, with us that soon happens. Well, still in a funk, eh? How many times did you think you were going to die last night, eh? Tell me, now.”

“Nay, but judge fairly. In the first place, what sort of a job was I on? Why, I might have ruined my soul for ever!”

“Well, I should like it all over again. What do you say?”

“Over again? Nay, that’s a little too … how shall I put it? Is it worth it? That’s where it is.”

“What, not for two rainbows?”

“Two hundred roubles you mean? Not if I know it. Why, I ought.

“Stop. How about ruining your soul, eh?”

“Well, you see, I might … even if you didn’t,” smiled Gabriel; “instead of ruining yourself you’d be a made man for life, no doubt.”

Chelkash laughed merrily.

“All right, we must have our jokes, I suppose. Let us go ashore. Come, look sharp!”

“I’m ready.”

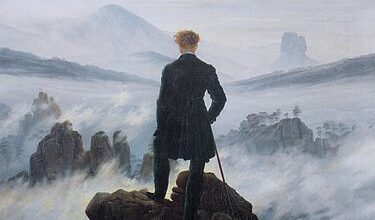

And again they were in the skiff, Chelkash at the helm, Gabriel with the oars. Above them the grey sky was covered by a uniform carpet of clouds, and the turbid green sea sported with their skiff, noisily tossing it up and down on the still tiny billows, and sportively casting bright saline jets of watertight into it. Far away along the prow of the skiff a yellow strip of sandy shore was visible, and far away behind the stern stretched the free, sportive sea, all broken up by the hurrying heads of waves adorned here and there with fringes of white sparkling foam. There, too, far away, many vessels were visible, rocking on the bosom of the sea; far away to the left was a whole forest of masts, and the white masses of the houses of the town. From thence a dull murmur flitted along the sea, thunderous, and at the same time blending with the splashing of the waves into a good and sonorous music…. And over everything was cast a fine web of ashen vapour, separating the various objects from each other.

“Ah, we shall have a nice time of it this evening,” and Chelkash jerked his head towards the sea.

“A storm, eh?” inquired Gabriel, ploughing hard among the waves with his oars. He was already wet from head to foot from the scud carried across the sea by the wind.

Chelkash grunted assent.

Gabriel looked at him searchingly.

“How much did they give you?” he asked at last, perceiving that Chelkash was not inclined to begin the conversation.

“Look there,” said Chelkash, extending towards Gabriel a small pouch which he had taken from his pocket.

Gabriel saw the rainbow-coloured little bits of paper,[1] and everything he gazed upon assumed a bright rainbow tinge.

[1] Bank-notes.“You are a brick! And here have I been thinking all the time that you would rob me. How much?”

“Five hundred and forty. Smart, eh?”

“S-s-smart!” stammered Gabriel, his greedy eyes running over the five hundred and forty roubles before they disappeared into the pocket again. “Oh my! what a lot of money!”—and he sighed as if a whole weight was upon his breast.

“We’ll have a drink together, clodhopper,” cried Chelkash enthusiastically. “Ah, we’ll have a good time. Don’t think I want to do you, my friend, I’ll give you your share. I’ll give you forty, eh? Is that enough for you? If you like you shall have ’em at once.”

“If it’s all the same to you—no offence—I’ll have ’em then.”

Gabriel was all tremulous with expectation, and not only with expectation, but with another acute sucking feeling which suddenly arose in his breast.

“Ha, ha, ha! That’s like you! What a tight-fisted devil you are! I’ll take ’em now! Well, take ’em, my friend; take ’em, I implore you. I really don’t know what I might do with such a lot of money. Relieve me of it! Do take it I beg!”

Chelkash handed Gabriel some nice bank-notes. The latter seized them with a trembling hand, threw down the oars, and began concealing the cash somewhere in his bosom, greedily screwing up his eyes and noisily inhaling the air, as if he were drinking something burning hot. Chelkash, with a sarcastic smile, observed him, but Gabriel soon took up the oars again, and rowed on nervously and hurriedly, as if afraid of something, and with his eyes cast down. His shoulders and ears were all twitching.

“Ah, you’re greedy! Isn’t that good enough? What more do you want? Just like a rustic!” said Chelkash pensively.

“Ah, with money one can do something,” cried Gabriel, suddenly exploding with passionate excitement. And gaspingly, hurriedly, as if pursuing his own thoughts and catching his words on the wing, he talked of life in the country, with money and without money, honour, contentment, liberty, and hilarity.

Chelkash listened to him attentively with a serious face, and with eyes puckered with some idea or other. At times he smiled a complacent smile.

“We have arrived!” cried Chelkash, at last interrupting the discourse of Gabriel.

A wave caught the skiff and skilfully planted it on the strand.

“Well, my friend, here’s the end of the job. We must drag the boat a little further in shore that it may not be washed away. And then you and I will say good-bye. It is eight versts from here to the town. What are you going to do?—back to town, eh?”

A sly, good-natured smile lit up the face of Chelkash, and he had all the appearance of a man meditating something very pleasant for himself and unexpected for Gabriel. Dipping his hand into his pocket he crinkled the bank-notes there.

“No … I—I’m not going! I—I….” Gabriel breathed heavily, as if struggling with something. Within him was raging a whole mob of desires, words, and feelings, mutually devouring each other and filling him as if with fire.

Chelkash looked at him doubtfully.

“Why are you twisting about like that?”

“It’s because, because….” But the face of Gabriel was burning red at one moment and deadly grey at another, and he was glued to the spot, now desiring to fall upon Chelkash, and now torn by other desires, the fulfilment of which was difficult for him.

Chelkash did not know what to make of such a state of excitement in this rustic. He waited to see what would come of it.

Gabriel began to laugh in an odd sort of way, it was more of a howl than a laugh. His head was lowered, the expression of his face Chelkash did not see, but the ears of Gabriel, alternately reddish and palish, were painfully prominent.

“Come, what the devil’s the matter,” said Chelkash, waving his hand, “have you fallen in love with me all at once? What’s up? You change colour like a wench. Sorry to part from me, eh? Eh, blockhead? Say what’s the matter with you, and I’ll be off.”

“Going, are you?” shrieked Gabriel shrilly.

The sandy and desolate shore trembled beneath his cry, and the yellow billows of sand, washed by the billows of the sea, seemed to undulate. Chelkash also trembled. Suddenly Gabriel bounded from his place, threw himself at the feet of Chelkash, embraced them with his arms, and turned towards him. Chelkash staggered, sat down heavily on the sand, gnashed his teeth, and cut the air sharply with his long arm, clenching his fist at the same time. But strike he could not, being stayed by the shamefaced supplicating whisper of Gabriel:

“Dear little pigeon…. Give me … that money! Give it to me, for Christ’s sake!… What is it to you? Why, it was gained in a single night … in a single night!… It would take me years…. Give it me … I’ll pray for you if you will! Perpetually … in three churches … for the salvation of your soul! Look now, you’d scatter it to the … winds … I would put it into land. Oh, give it to me! What is it to you?… How can you prize it? A single night … and you’re a rich man. Do a good act! You’re all but done for…. You haven’t got your way to make. But I would…. Oh! give them to me!”

Chelkash, alarmed, astonished, and offended, sat on the sand, leaning back, supporting himself on his arms; he sat there in silence and fixed a terrible gaze on the rustic who had buried his head in his knees, sobbing as he whispered his petition. He repulsed him at last, leaped to his feet and, thrusting his hands into his pockets, flung the rainbow bank-notes to Gabriel.

“There, you dog! Devour…!” he cried trembling with excitement, bitter sorrow and loathing for this greedy slave. And he felt himself a hero for thus throwing away the money. Reckless daring shone in his eyes and lit up his whole face.

“I was going to give you more of my own accord. I was a bit down in the mouth yesterday, and bethought me of my own village. I thought to myself: let us give this rustic a helping hand. I was waiting to see what you would do. If you asked you were to get nothing. And you! Ugh! you miser! mean hound! To think that it is possible so to lower oneself for money I Fool! Greedy devils the lot of you! Not to recollect yourself! To sell yourself for a fiver! Ugh!”

“Dear little pigeon! Christ save you! Now I have got something … a thousand! Now I am rich!” cried Gabriel in his enthusiasm, all tremulous as he hid his money away in his bosom. “Ah, you merciful one! Never will I forget it … Never!… And I’ll make my wife and children pray for you.”

Chelkash listened to his joyous cries, looked at his radiant face deformed by the rapture of greed, and he felt that he, thief, vagabond, and outcast though he was, never could be so greedy, so mean, so forgetful of his own dignity. Never would he be such a one! And these thoughts and sensations, filling him with the consciousness of his large mindedness and nonchalance, held him fast to Gabriel by the sandy sea-shore.

“You have made me happy!” shrieked Gabriel, and seizing the hand of Chelkash he pulled it towards his face.

Chelkash was silent, and fleshed his teeth like a wolf. Gabriel continued to pour forth his heart to him:

“Do you know what was in my mind?… We came here—I saw the money…. Thinks I … I’ll fetch him one … you I meant … with the oar—c-c-crack! The money’s mine and he … that’s you … goes into the sea…. Who would ever light upon him? And if they did find him they would never inquire how he was killed or who killed him … such a fellow as that! He’s not the sort of man people make a fuss about!… He’s no good at all in the world! Who would ever trouble about him? You see how….”

“Give up that money!” howled Chelkash, seizing Gabriel by the throat.

Gabriel tore himself away—the other hand of Chelkash twined round him like a serpent—there was the grating tear of a rent shirt, and Gabriel lay on the sands with senseless goggling eyes, with sprawling feet and the tips of his outstretched fingers fumbling for air. Chelkash stiff, dry, and savage, with grinding teeth, laughed a bitter spasmodic laugh, and his moustaches twitched nervously on his clear-cut angular face. Never in his whole life had he felt so angry.

“What, you’re lucky, eh?” he inquired of Gabriel in the midst of his laughter, and turning his back upon him, went right away in the direction of the town. But he hadn’t gone a couple of yards when Gabriel, with his back arched like a cat, rose on one knee, and taking a wide sweep with his arm, threw after him a large stone, crying spitefully: “Crack!”

Chelkash yelled, put both his hands to the back of his head, tottered forward, turned towards Gabriel, and fell prone in the sand. Gabriel’s heart died away as he gazed at him. There he lay, and presently he moved his foot, tried to raise his head, and stretched himself, quivering like a bow-string. Then Gabriel set off running away in the direction of the misty shore, it was overhung by a shaggy black cloud, and was dark. The waves were roaring as they ran upon the sand, mingling with it and then running back again. The foam hissed, and the sea-scud was flying about in the air.

The rain began to fall. At first there were but rare drops, but soon it poured down in torrents, descending from the sky in long thin jets, weaving a whole net of water-threads—a net suddenly hiding away within it the steppes and the sea, and removing them to an immense distance Gabriel vanished behind it. For a long time nothing was visible except the rain, and the long lean man lying on the sand by the sea. But behold I again from out of the rain emerged the running Gabriel; he flew like a bird and, running towards Chelkash, fell down before him, and began to pull him about on the ground. His hands dipped into the warm red slime. He trembled and staggered back with a pale and stupid face.

“Brother! get up! do get up!” he whispered in the ear of Chelkash amidst the din of the sea.

Chelkash came to himself and shoved Gabriel away, hoarsely exclaiming: “Be off!”

“Brother, forgive!… the devil tempted me!” whispered the tremulous Gabriel, kissing Chelkash’s hand.

“Go! Be off!” growled the other.

“Take the sin from my soul, my brother! Forgive!”

“Slope! Go to the devil, I say!” cried Chelkash, and with an effort he sat up on the sand. His face was pale and angry, his eyes were dull and half closed, as if he wanted to sleep. “What more do you want? You have done what you wanted to do…. So go! Be off!” and he tried to kick the utterly woe-begone Gabriel, but could not, and would again have rolled over had not Gabriel held him up by embracing his shoulders. The face of Chelkash was now on a level with the face of Gabriel; both were pale, pitiful, and odd-looking.

“Phew!” said Chelkash, and he spat full into the wide-open eyes of his workman.

The latter gently wiped it off with his sleeve.

“What would you do? Won’t you answer a word? Forgive me, for Christ’s sake!”

“Ugh, you horror! But you’ll never understand,” cried Chelkash contemptuously, dragging off his shirt from under his short jacket and proceeding to wrap it round his head in silence, save for the occasional gnashing of his teeth. “You have taken the notes, I suppose?” he muttered through his teeth.

“No, I’ve not taken them, my friend!… I don’t want them … they’d do me harm!”

Chelkash shoved his hand into the pocket of his jacket, drew out a bundle of money, put back again in his pocket a single rainbow note, and pitched all the rest at Gabriel.

“Take it and go!”

“I’ll not take it, my brother … I cannot I Forgive me!”

“Take it, I say!” roared Chelkash, rolling his eyes horribly.

“Forgive me … and then I’ll take it!” said Gabriel timidly, and fell on his knees before Chelkash on the grey sand, now saturated with rain.

“Take it, you monster!” said Chelkash confidently, and, with an effort, raising Gabriel’s head by the hair, he flung the money in his face. “There, take it! You shan’t work for me for nothing. Take it without fear! Don’t be ashamed of nearly killing a man. Nobody will bother about such as I. They’ll even thank you when they hear about it. Come, take it! Nobody knows about your deed, and it’s worth a recompense. There you are!”

Gabriel perceived that Chelkash was laughing at him, and his heart grew lighter. He grasped the money tightly in his hand.

“But, brother, you forgive me, won’t you?” he inquired tearfully.

“What for, my brother?” said Chelkash in the same tone, rising to his feet and tottering a little. “What for? For nothing at all. To-day it’s your turn, to-morrow mine.”

“Alas, my brother, my brother!” sobbed the afflicted Gabriel, shaking his head.

Chelkash stood in front of him with a strange smile, and the rag round his head, now slightly tinged with red, bore some resemblance to a Turkish fez.

The rain was pouring down as if from a bucket The sea raged with a muffled roar, and the waves now beat upon the shore with frantic rage.

For a time both men were silent.

“Well, good-bye!” said Chelkash coldly and sarcastically, and set off on his journey.

He staggered as he went, his feet tottered beneath him, and he held his head so oddly, just as if he were afraid of losing it.

“Forgive me, brother!” Gabriel besought him once more.

“Bosh!” coldly replied Chelkash, pursuing his way.

On he staggered, supporting his head all the time in the palm of his left hand, while with his right he gently twirled his fierce moustache.

Gabriel continued to gaze after him till he disappeared in the rain, which was now pouring down more densely than ever from the clouds in fine endless jets, enveloping the steppe in an impenetrable mist of a steely hue.

Then Gabriel took off his wet cap, crossed himself, looked at the money fast squeezed in his palm, sighed deeply and freely, hid the notes in his bosom, and With a spacious confident stride marched off along the sea-shore in the direction opposite to that in which Chelkash had vanished.

The sea howled, and cast huge heavy waves on the strand, churning them up into foam and scud. The rain cut up sea and land furiously. Everything around was filled with howling, yelling, moaning. Neither sea nor sky was visible behind the rain.

Soon the rain and the wash of the waves had cleansed the red spot on the place where Chelkash had lain, had washed away all traces of Chelkash, and all traces of the young rustic from the sand of the sea-shore. And on the desolate strand nothing remained as a memorial of the petty drama played there by two living souls.