“Closer To a Pet.” How Women Were Viewed by 19th-Century America

The United States was about to turn ninety-four. The Civil War had ended seven years earlier, leaving Americans wary of the next great upheaval. When Mamie Ware was six months old, Susan B. Anthony illegally cast a ballot. When she was two, Alexander Graham Bell assembled his first telephone. In her eighth year, Edison patented his light bulb.

Mamie’s “blessedly humorous” father, George, died of cancer in 1882, the year she turned ten. He had made an uncertain living as a hide and wool merchant, moving his young family from his native Worcester, Massachusetts, to San Antonio, Texas, and back again in the hopes of stabilizing their income. But illness came too soon for him, and he left his widow and their three living children, Mamie, Clara, and Willie, with little in the way of security.

Mamie’s mother, Livonia—Vonie, to her family—had no time to retreat into mourning. Her decisions reflected the hopes for self-sufficiency and worldliness she had for her family. She went into business as a tutor-chaperone for young women taking grand tour-inspired trips to Europe. (On one of these journeys she was forced to delay her trip home when a student came down with appendicitis, missing the passage she had booked on the Titanic.)

Since the colonial era, American women had taken issue with their absence from the nation’s founding documents.

With her mother overseas for long stretches each year, Mamie grew up independent but rarely alone. The Wares lived in Boston now, in a brownstone on Saint James Avenue, with Vonie’s siblings Lucia, Clara, and Charles Ames, as well as a rotating cast of boarders and guests.

Most influential was Aunt Lucia, who tolerated the nickname “Ah Loo” from Mamie. She was a “beloved auntie” and “a wonder,” who maintained a “grand outside calm” in the face of any worry. She was also a nationally eminent social reformer. Nearby lived an even grander relative, Charles Carleton Coffin, who’d been a famous Civil War correspondent. Mamie loved the imposing stateliness of Coffin’s four-story house on Dartmouth Street. At least once a year, he staged lantern slide shows for the children and organized Christmas parties at which his friend Louisa Alcott joined for charades.

Living with her relatives, Mamie soon learned of the tendency toward defiance woven into her lineage. Vonie’s people, the Coffins, were a storied family. Levi Coffin (1798–1877) of Cincinnati smuggled more than three thousand enslaved people to freedom. Slave hunters called him the president of the Underground Railroad, and it was rumored that Harriet Beecher Stowe modeled two characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin on Levi and his wife. Another relative, Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793–1880), was a formidable advocate for abolition and women’s suffrage. With a small group of like-minded women, including her sister Martha Coffin Wright and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she helped organize America’s first formal women’s rights rally, the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848.

The torchbearer of this legacy in Mamie’s household was Lucia, who became head of the Massachusetts Suffrage Association in 1903 and cofounded the Women’s Peace Party in 1915. As Lucia Ames, she had expected to remain single for life and was skeptical any benefit could be worth the servitude required by marriage. At forty-two, however, she married Edwin Doak Mead, the editor of the New England Magazine and also a world-peace activist. The pair exemplified the “socially impeccable progressive” set—devotees of Emerson and Thoreau, admirers of Tolstoy and the political economist Henry George—and they formed a companionate union that was Mamie’s most lasting ideal of married life.

As generous as the Meads were, Mamie sometimes felt like a dud among them. One moment very close to the time of her father’s death came to form the basis of her strongest, harshest view of herself, even years later. She was outside a room and happened to overhear Edwin Mead remark, “Mary is certainly about the most uninteresting unattractive child imaginable.”

Mead likely spoke in a moment of tiredness or light malice—after all, he was much in the company of this clever, needy child. He came to love her dearly. But to Mamie, Mead’s words “echoed right straight through my whole life and have never lost their grip,” she later confessed to her children. “They all but successfully antidoted the ‘I love you’ from the two men who have been closest to me.”

But they also gave her something: expanded empathy. “It is a pretty big handicap, God knows, to be uninteresting and unattractive,” she wrote, “but still it is a handicap one has in common with many others, and it surely gives a sympathy and fellow feeling that perhaps can’t come any other way.” The wound became part of who she was.

*

While Mamie Ware was growing up, womanhood itself was going through a metamorphosis. It had been more than a century in coming. Since the colonial era, American women had taken issue with their absence from the nation’s founding documents. In the spring of 1776, Abigail Adams asked her husband to “remember the ladies” in the new nation’s “code of laws.” John Adams found his wife’s request funny, comparing it with the irrational demands of a willful child, servant, or slave. “But your Letter,” he noted, “was the first Intimation that another Tribe more numerous and powerfull [sic] than all the rest were grown discontented.” He knew that statement had an unkind ring to it but thought it justified, adding, “This is rather too coarse a Compliment but you are so saucy, I wont blot it out.”

Abigail was undaunted. “We are determined to foment a rebellion,” she wrote back to him presciently, “and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

Such words must have seemed near fantastical at the time. Convention and the Constitution, implicitly and explicitly, decreed there was one dominant, default type of citizen for whom rights and laws were made. For women to seek a direct voice in public life meant calling into question all the received ideas about gender that then governed society and the state. By the late nineteenth century, a vibrant movement had risen up to dismantle what had been a clear hierarchy of the sexes and reestablish it in a different pattern: a binary. In politics women were invisible; in the household, they were permitted to rule.

Science said a woman was closer to a pet than equal to a man. As an 1848 medical tract explained, “She has a head almost too small for intellect but just big enough for love.” Darwin himself mused about women’s capacities in his journal, concluding that his ideal would be “a nice soft wife,” “an object to be beloved and played with. Better than a dog anyhow.” (For the record, Darwin loved dogs.)

Despite Darwin himself holding this view, his studies supplied a framework suggesting inequality of the sexes was socialized, not divinely or biologically decreed. “Nowhere in all nature is the mere fact of sex…made a reason for fixed inequality of liberty, of subjugation, of subordination, and of determined inferiority of opportunity in education, in acquirement, in position—in a word, in freedom,” wrote the feminist Helen Hamilton Gardener in 1893. “Nowhere until we reach, man!” For many, Darwin’s work supplanted the Christian dogma that said woman was created to be man’s helpmeet.

For women to seek a direct voice in public life meant calling into question all the received ideas about gender that then governed society and the state.

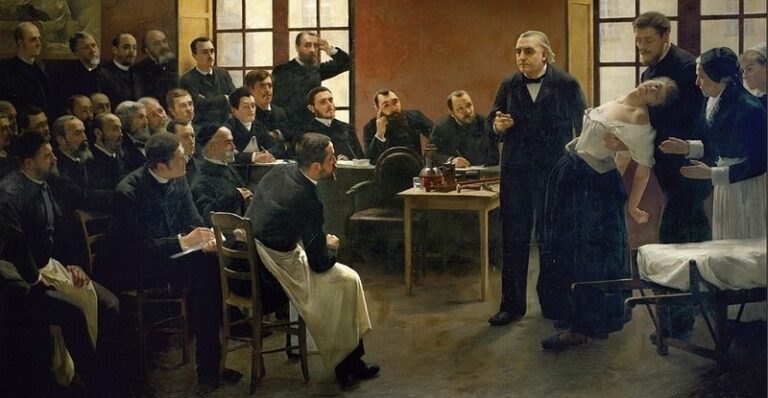

Medically speaking, a nineteenth-century woman was an extension of her reproductive tract, though prone to glitches. A New Haven professor lecturing to a medical society in 1870 asked his listeners to imagine that “the Almighty, in creating the female sex, had taken the uterus and built up a woman around it.” “Woman’s reproductive organs are pre-eminent,” one physician wrote. “They exercise a controlling influence upon her entire system, and entail upon her many painful and dangerous diseases. They are the source of her peculiarities, the centre of her sympathies, and the seat of her diseases. Everything that is peculiar to her, springs from her sexual organization.” Based on this theory, the root cause of any illness could be ascribed to hysteria, all symptoms traced back to the troublesome, restless womb.

A woman’s purpose in the world was driven by her fertility—or her infertility. Women who couldn’t have children had their mystification and pain compounded by the conviction it was their own fault. Until the 1930s, childlessness was assumed to be the result of women’s bodies and minds going awry. A childless woman was barren, a field too marred and poisonous to nurture new growth. In Hippocrates’s time, barrenness could result from a uterus that was too wet, too dry, or malformed. Later authorities theorized there were nonphysiological causes, too: a surfeit of reading, education, or mental excitement; lack of pleasure in sex; or plain old overthinking it.

Too much information or deep study was not only improper, but physically detrimental to women. In Sex in Education, an influential 1873 study by a Harvard professor, Dr. Edward Hammond Clarke, a parade of case studies tried to persuade readers that college education had devastating health consequences for female students. After observing that many women around him were invalids, and noting the rising trend for sending girls to college, Clarke concluded there was a causal relationship. Young women, he asserted, did not have the capacity to develop their minds and reproductive systems at the same time. Unlike men, in whom the brain and heart were the primary organs, he was convinced women were dominated by their ovaries, which risked shriveling or turning cancerous if forced to share a body with an overactive brain.

The book was more of a sermon than a study; Clarke had barely any statistics supporting his thesis. Despite this total disregard for scientific methodology, his book went through seventeen printings and was widely read.

For eugenics boosters, a woman was a means of production—though a fickle and confounding one. The fruits of her body perpetuated every hereditary trait: a wildly unpredictable and potentially devastating power. Eugenicists looked forward to a future when that generative power could be regulated. Entire populations and nations could be grown by design.

Part of birth control’s appeal, for eugenicists, was the opportunity to suppress the reproductive freedom of Black and brown women, immigrants from southern Europe, Catholics, unwed mothers, and people with disabilities. While in theory aimed at bolstering public health, in practice eugenics put a scientific sheen on white supremacy and ableism, under the pernicious guise of “purity.”

__________________________________

From The Icon and the Idealist: Margaret Sanger, Mary Ware Dennett, and the Rivalry That Brought Birth Control to America by Stephanie Gorton. Copyright © 2024 by Stephanie Gorton. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.