Containment and Freedom: In Praise of the Boarding School Novel

The first half of Alice Winn’s bestselling In Memoriam is set at Preshute, an English boys’ boarding school in the early twentieth century. It is here, in the idyllic countryside, where the boys discuss poetry and get up to all sorts of high-jinks and japes, and where two students, Gaunt and Ellwood, fall in love. Then the boys are ejected into the horror and abyss of WWI trenches. When they are reunited, mentally and physically scarred, Preshute is but a dream and their adolescent love, a halcyon place that can only be returned to in memory.

Everyone loves a good boarding school novel. Spanning both childhood and adolescence, these settings dominate children’s literature (from Enid Blyton to J.K. Rowling) and are rich sites for both YA and adult fiction (from Ursula K. Le Guin to Curtis Sittenfeld, Robert Musil to Muriel Spark, Alan Hollinghurst and Kazuo Ishiguro). It is precisely because they distill and contain all the pain and pleasure of being young into one crucible that they are such rich source material for novelists. Fiction thrives on change, and what bigger, more painful transformation is there than becoming a teenager?

It’s not just what goes on in boarding schools, but the places themselves that offer writers a perfectly contained structure to work with—and against.

Of course, not everyone can go to boarding school. King’s School, Canterbury, the oldest boarding school in England dates back to 597 AD. More elite than university even, the boarding school occupies a fantasy space in the writer’s imagination, making novels about them a tantalizing glimpse into another world. Hogwarts is the ultimate version of this, but any novel set in a boarding school draws some of its allure from this mythical place.

And oh, the pressure-cooker atmosphere of the boarding school is irresistible for novelists! Yes, the children might be the coddled offspring of the ultra-wealthy, but they suffer too—and in such a contained and specific space that Aristotle would be delighted to call it tragedy. There’s the pressure to excel in lessons and pass exams that has no release from a home-life outside of school. Often the boarding school is a site for terrible trauma. Young children torn away from their beloved parents and thrown into a cold, strict environment, dominated by the threat of punitive authority. Left to their own devices, children often replicate these systems of abuse: think of Lord of the Flies, where the boys descend into complete barbarism and cannibalism. Even Alice Winn’s Preshute is not safe from bullies and sadists.

Yet, it is not all draconian rules and tears. Far away from the city and its dangerous influences, boarding school settings create a bucolic bubble that protects the student. But as the garden of Eden is only a dream, so the bubble must be popped. School, like childhood, like innocence, comes to an end. Inherent to the boarding school novel, then, is a deep sense of loss—an emotional gut punch that is a gift for any writer.

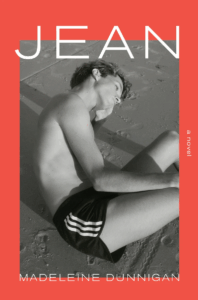

It is this existential anguish that I wanted to tap into when writing Jean. The novel is set over one hot summer in 1976 in the final year of Jean’s time at Compton Manor, a rural, English, hippie boarding school for boys with “problems.” I knew I wanted to write a novel about a teenage boy who felt at odds with the world around him, but it took me some time to find my structure—an early draft of the novel spanned eighty years and had multiple narrative perspectives. The boarding school setting provided me with a framework in which to explore Jean’s feelings of alienation. Jean is seventeen. He is old enough to transgress authoritative structures but too young to think about his future. It is in this liminal space—where Jean dreams of being someone and somewhere completely different, and where, that fantasy seems a possibility, only to be shredded—that my novel sits.

I don’t know what it is like to attend boarding school, especially not a boys’ boarding school in the seventies, but I do know what it feels like to be a lonely, angry teenager. School can be an awful place, where social capital is built on a person’s acceptance by a group, and any difference is sniffed out and mocked, sometimes worse. Boys’ boarding schools are the most extreme example of this. Compton Manor both conforms and differs from this: based on “hippie” principles, its paradigm of authority is complicated. It is a place where wealthy families can silo their troubled teens and hope for a cure in the form of “alternative” education. But even in this environment Jean is an outcast: antisocial, violent, fatherless and the son of a bohemian, unmarried, Jewish refugee mother. If the boarding school setting dramatizes the dichotomy between outsider-insider, Jean is an attempt to push this to its extreme.

Add to this the intensity of puberty. The erotic potential of hormonal teenagers all forced to live, work and sleep together has been exploited in numerous novels—and exploited often by the characters themselves: in Alice Winn’s Preshute, sexual exploits between boys is a regular occurrence; while Robert Musil’s Young Törless, a novel set in an Austrian military academy that documents the protagonist’s sado-masochistic activities, pushes these to abusive extremes. So, too, such events occur at Compton Manor, but this is where Jean differs. His sexuality is a conduit to human connection rather than dominance. But just like Gaunt in Alice Winn’s In Memoriam he must find a way to navigate this powerful desire whilst also grappling with internalized (and external) homophobia. Desire is possibly the most enduring writer’s preoccupation: the boarding school setting allows them to explore the genesis of this in all its beautiful, clumsy, painful glory. Because there is nothing better, and nothing worse, than teenage heartbreak.

At its heart, the boys’ boarding school is about containment and freedom. Despite its abuses of power, it is still, for so many, home.

It’s not just what goes on in boarding schools, but the places themselves that offer writers a perfectly contained structure to work with—and against. Lessons, mealtimes, recreation. Plot is not simply a series of moments that plod one after another, but the knitting together of causally linked events. What the boarding school setting provides is a clear structure against which to map these events. Writing is a series of decisions. From the specific—like, what does my character eat for breakfast?—to the abstract—what does my character think they want? What do they actually want? And, even, what does this say about the meaning of life? Knowing where your character is meant to be, what they are meant to be doing, with whom, and when, removes a swathe of decision making. And, of course, boarding schools themselves can be immensely silly, dominated by boys’ pranks, rebellions, and mishaps. This combination of a clear structure and a license to play lets the writer have fun. Now the character skips lessons. Now he meets someone secretly. Now he falls in love.

The boarding school setting not only provides structure, but it creates depth. Against a background of learning, characters are shaped in situ. Lessons that change a character’s perspective forever—think John Keating, the unconventional English teacher, in Dead Poets Society—sports that make him feel alive, interactions that show him what living is. Away from the bullies and the authoritarian regimes there can be inspiration and epiphanies. Teenagers can be the worst proponents of the monosyllable; they can also be unbelievably pretentious. The boarding school offers a rich background against which both modes can flourish.

The boys’ boarding school is a site of transgression, and this makes it a crucible for narrative escalation: a small pool of characters forced repeatedly to interact inevitably creates drama. At its heart, the boys’ boarding school is about containment and freedom. Despite its abuses of power, it is still, for so many, home. As a writer, I am drawn repeatedly to the memory of my own turbulent adolescence: never have I felt so much rage, never again, so much joy, or such a sense of freedom. It was these extremes I wanted to capture in Jean; and it was through the boarding school setting that I was able to do so. Compton Manor is both a sanctuary and prison. It is here, in this inferno of learning and rebellion, danger and potential, conformity and individuation, where Jean transforms, and it is in that space—between the loss of innocence and the acquiring of knowledge—that the novel takes shape.

__________________________________

Jean by Madeleine Dunnigan is available from W.W. Norton & Company.