“Endlings”

I started watching the Warrens’ children because my mother’s dead sister was hanging around, giving everyone a hard time. That was how I met the Warrens: my mother’s letter made its way across town to Ed’s desk. Between her many digressions and charmingly articulated grievances, Ed seemed to have discerned its truth: that we were a family troubled, and in desperate need of assistance.

He arrived with Lorraine on a Tuesday in November, in a silk shirt and a brocade-patterned scarf knotted tightly around his throat, and did the entirety of the house walk-through in his sunglasses. Lorraine recorded our conversations with a thoughtful expression, asking my parents probing questions I wished she were asking me. My mother took to her immediately, clinging to her arm and wailing about the situation. We had been respectable, ordinary people until the comet, she said. Now her dead sister was fiddling with the plumbing, spooking the cat, spoiling the canned goods.

My father followed the parade of us silently. I could, with practice, sense his thoughts about my mother’s emotional excesses, and that of women in general. He was embarrassed. Lorraine patted my mother’s arm and assured her that she believed her. The comet had been rustling up quite a lot of supernatural activity where you least expected it. Major cosmic events did that: lifted old patterns like long-sunk bodies from the swamp that’d swallowed them. Distorted time. Made people and animals and, yes, even ghosts act on their strangest impulses. It was possible, she said, that the dead woman didn’t even know she was dead. My mother sobbed at this news. Lorraine took her to the kitchen and made her tea. My mother asked me to follow them, to the room with the women, but I refused; I loved Lorraine’s perfume but my mother never went anywhere interesting. Instead I followed Ed, and my father, deeper into the house.

When we arrived at the most haunted room—mine, nestled in the northwestern corner—Ed removed his sunglasses and examined the furniture in great detail. He searched for my aunt in drawers and shoeboxes. He uncovered my diary and took in a few pages to understand what it was, but quickly hid it again, to prevent my mother from seeing it. He set up a device to measure the many qualities of the room. He also sat down at my desk and interviewed me about the situation. Had I seen my aunt? he asked. The chair creaked under his weight.

I had. I knew when she would arrive; her presence was preceded by a bitter tang on the air, like a fine perfume that had gone rancid in the heat. And I knew she was in the room because she would set up next to my ear and whisper to me all the ways in which I was awful. (I was prideful and arrogant, smug and self-satisfied, pleased with my own intelligence, certain of what I knew.) She sat there, I said, like a frog on a toadstool, telling me that I was a wretched daughter and worse niece; that my parents’ marriage was sinking like a poorly maintained skiff in moderately difficult weather; that my own insufficiencies were like mice chewing at the boat’s infrastructure, not the cause of the sinking but an undeniable factor in the loss. And then she would throw a fit: hurling my underthings into the air, jerking books off my shelves, shocking me whenever I touched the telephone.

“Your mother didn’t mention any of this,” Ed said.

“Well,” I replied, “she’s also killed the hydrangeas.”

“Do you have any idea why your aunt is doing this?” he asked. “Why is she not resting in her heavenly reward?”

I had theories. My aunt had a been a difficult and frankly terrible woman; she had hated me particularly for reasons that were never clear, and she had died in an acutely humiliating way. (An accident whose details my parents withheld from me but which caused my father to excuse himself to the basement to laugh.) If she was in heaven, I said, it was news to me.

Ed took notes as I spoke, in a kind of shorthand that I did not know at the moment but would come to be able to read quite fluently. He watched me from over his glasses. Did I often encounter spirits? he asked. Hear their voices, see their manifestations? Was I ever plagued by memories that were not my own or write things in an unknown hand? Did rocks ever pelt the roof of my house? Was I able to discern the suit of unseen playing cards? Wish things into reality from my own imagination? Move objects with my mind? I told him the truth, or the truth as best as I understood it: I was born under an erratic star at an unknown hour and was fixed in neither this world nor the next. Here, Ed paused. He peered out the bedroom door into the hallway, which was empty. Then he spoke. He did not say, Why do you talk like that? He did not say, Whatever is wrong with you? He did not say, Why this fixation on the darkness?

“Do you like children?” Ed asked. I loved the way the question plucked me from among them, set me apart.

“I do,” I said. “I am very good with children.”

Ed cleared his throat and stood up. He was going to interview my father next, he told me.

Good luck, I said. My father was not the best at paying attention, especially when things did not interest him. He knew much but he could not see. Where my mother had too much texture, my father had far too little.

“You are very honest,” Ed said. He did not sound judgmental. His voice was admiring. “Most people are too overwhelmed with fear or feeling to be honest. But you have great clarity.”

Thank you, I said. I had been waiting for someone to notice.

*

A week after Ed entombed an emblem of my aunt’s spirit in a very tiny glass bottle, he called my mother to ask if I would be permitted to take on a regular babysitting job with some light administrative duties. Their last sitter/secretary, Gerrie, had moved away, gone to–my mother said—“Colombia.”

“The university or the country?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she said. Then she said, “Three children are too many.” When she was a girl, she said, the babysitters had a union. There were rules about the rate per child, about household labor. To take a teenage girl away from her family—especially now, especially with the comet and the changes—you owed a girl at least seventy-five cents an hour. Was his house haunted? she asked. Didn’t they say the comet had rustled up old stories? Who could be more haunted than a ghost hunter? By his logic they should be the most haunted of all. They made the dead deader. She asked my father to weigh in—once, twice, and then so loudly I covered my ears. His voice drifted up from the basement but the words were indistinct. “See?” my mother said.

I went and stood at the top of the stairs, listening for him in the darkness. But whatever he had to say, it was over now.

The Warrens’ house was beautiful—a huge, looming Queen Anne with more personality than my entire family. It sat on a sprawling half acre of dramatic, cinematic vegetation—garden paths that led from one part of the property to the other; stands of trees with tiny stone benches; a shallow pond thick with koi; a tiny, locked shed with a narrow, locked door. Mystery on mystery on mystery. It was as if I’d wandered into one of the novels I loved to read, the kind I imagined writing one day.

The first time I saw Ed with his kids—in his yard, waiting for my arrival—he was overflowing with them, holding them up as if they were nothing. One on his back, one on his shoulders, one in his arms. That, I remember thinking, as the sun struck the lawn and turned it gold, that is how a father is supposed to look.

*

The hours I spent after school at Ed’s desk transcribing their backlog of recordings made me feel like my father, or how I imagined my father was at his job, whatever it was. Is this what it felt like to do business? I loved the efficiency of the typewriter, the slowly building sheaf of papers, the smell of wood and furniture polish, the width of the desk and the depth of the drawers: the stick-and-slide of them and how one of them was locked by a key that sat in Ed’s breast pocket.

And there was nothing more exciting than turning on a tape—which made a cousin sound to the oiled click of the key in the lock—and hearing Ed and Lorraine’s voices spilling into the room. How warm they were, how knowledgeable. How frequently their wisdom was interrupted by anecdotes about their children, about whom they were extraordinarily proud. They talked about them often, in between and during their assessments. A poltergeist made them nostalgic for the older children’s toddler years. A demon reminded them that their children would one day be teenagers, alien and willful. And once, when they encountered La Llorona, Lorraine wept for the spirit’s lost children, even though it was she, La Llorona, who had murdered them. On the tape, her weeping became muffled in Ed’s shirt. I listened for La Llorona but the hiss and crackle of the tape yielded nothing but the grain of the air and Lorraine’s sniffles. Ed apologized, and the tape ended.

“To hear, to understand, to make change, you have to listen with no judgment,” he said to me once. “Keep your emotions in check. Or else you’ll disrupt the ecosystem.” This was what he called all of it—the physical location of the haunting, the haunted, and the haunters, all together. It was like a family, he said. Each member was essential to the matrix.

*

My impression of the Warrens from their exorcism of my family home—that Ed worked the machines and Lorraine managed the personalities of the afflicted—had not been correct. They had simply responded to my family’s unconscious biases, like the best service workers. Lorraine was in fact better with the equipment; she understood it intimately and it responded to her like a seeing eye dog. Sometimes when I arrived for the evening, I would find her standing on the lawn with a machine in her hand, taking a reading of some faint spirit miles from where we stood. It felt like I was watching her man a boat down a river with a blindfold on.

“A restless soldier,” she said one time, by way of explanation. “A regretful witch,” she said another time, lifting the device a little higher. The afternoon of the party, she was pointing it directly at the sky, directly at the comet, which had been glowing brighter and brighter every day. I stood next to her. The lawn was a little overgrown and peppered with dandelions.

“It’s telling me something but I don’t know what,” she said. “Would you like to listen?”

She adjusted something, then lifted the headphones from her own ears and set them on mine. They were warm, and the pleasurable sensation of their warmth curled down my spine and into my body. When I finally found myself listening, the sound was—strange. Wet. It whimpered. A splash. None of it made sense. I knew from school: comets were not wet, they were frozen. Covered in snow. They did not whimper.

When she read my uncertain face, Lorraine took back the headphones. “Odd, isn’t it?” she said. The light crossed her face like an old movie. She was the most elegant woman I’d ever seen.

“Did you want me to do any transcribing tonight?” I asked.

“Oh no. Just the children tonight.” She patted me on the shoulder and walked inside. Her sillage hung in the air. I stood there in her wake, letting it curl around me like smoke.

*

A few months into my employment, the Warrens hired me to spend the night for one of their parties. This was not the first time I had watched the children in this manner; the Warrens were constantly entertaining. Sometimes for other academics—it was both easy to forget and easy to remember that Ed was a full professor at the local university—sometimes for donors whose interest in the super-natural loosened their wallets and their tongues. How many times had I come down to the kitchen for a plate and some unspeakably wealthy man had Lorraine in a corner, telling her about how he would wake up in the night and see a dark figure in the corner of his room and what did it mean? Was it coming for him? Seeking to end his life? Lorraine’s answers were soothing, empathetic, and designed to generate business: A ghost rarely wanted to injure the living but it was just as likely to want to tell you a story, get a bit of payback, or share a beloved recipe that had followed it to the grave. The only way to tell, she said, was to listen. With the right tools. Which they had spent years developing and learning how to use. And they had the room of haunted artifacts to prove it. Sometimes, Ed would bring me down to the basement to show them to me. He would give me a sip of his drink—“Don’t tell Lorraine,” he’d say, though I never knew if he was talking about the drink or the fact that I was handling possessed objects—and ask me if I could sense their aura; I would turn them from side to side and tell him what I felt, or what I imagined I felt.

The Warrens had friends over too. All the time. The other adults who arrived at those parties were mysterious. There was something unctuous and alluring about them. Lorraine set up a futon for me in the children’s room so I could spend the night sleeping next to them; she did not seem to want me to risk leaving around midnight or 2:00 a.m. or any other hour. I would lie there and listen to the house: the steady breathing of the children and groaning of the house making space within itself and the distant laughter of the Warrens and their acquaintances and then deep in the basement my terrible aunt tap-tap-tapping on the inside of that tiny glass bottle, seeking her revenge.

But this party was different. Special. It was a party for the comet, Lorraine said. In honor of the comet. In spite of the comet? Because of the comet. When she asked my parents if I could come, Lorraine told them a filmmaker would be documenting the evening and they needed to sign a waiver for me. I would probably not appear, Lorraine assured them, but there was no need to risk my slipping through the frame, ruining a shot. Was the documentary about the comet then, my mother asked. No: The documentary was about their work in the world of the supernatural—a precursor to cinematic ambitions that Ed had been nursing for years.

At home, my mother squinted at the waiver, trying to discern what exactly they were signing away. As she did every time I desired something, she resisted it as though it would kill her. She had questions. Was I often downstairs when the children were upstairs? Did I expect to be in the camera’s eye? Did I have ambitions of acting or performance? Would I find myself seeking out this filmmaker? Was he known to me? Was this film a sign that the Warrens were planning to expand their operations? Move elsewhere? Did they intend to take me with them? I was hardly around anymore. (This was accusatory.) It was the first time my parents ever acknowledged that the Warrens were famous, and that I, their daughter, oversaw their most precious commodities.

I stared at my mother as she spoke, making my face soft and unjudgmental, like I’d been practicing. But it was hard. I did not like the tone of her voice. I did not like the shape of her face or the feather of her hair. I did not like the cylinder of her torso or the way she wore her shoes. Perhaps I was as hateful as my aunt had said.

“The filmmaker is a woman,” I told her.

My mother threw her hands up in the air like I’d put a curse on her. She asked my father if I’d heard that. “Mmm,” he said, and stood up, like he had somewhere to be.

*

In the kitchen, the caterers were setting up chafing dishes overflowing with goulash and salmon loaf, and the party planner, Lucinda, was chain-smoking Viceroys over the sink. When she saw me she nodded and I felt more warmth move through me. Were we not all just employees of this magnificent enterprise? Comrades? I was no different than this anxious, extinguished woman tapping ash into a coffee mug. “They’re out back,” she said.

I slipped past the man bowling the salad and went into the backyard, where the light was becoming glossy and thick with evening. The children were there, tussling in the grass. Virginia was holding baby Barbara in her arms. She was seven but wanted to be a mother already. Didn’t we all? I mean, I didn’t, but I’d heard that this was why little girls craved their dolls. Walter was frantically digging in the dirt. At nine, he considered himself above a sitter, though he did enjoy showing me objects—rocks, seashells, baseball cards, mousetraps he’d liberated from the attic. Virginia called my name. “Mama says the comet won’t hurt anybody but we still can’t watch,” she said.

“You can see it now,” I said to her, pointing. “I think she means you can’t stay up for the party.” I looked over at Walter. “What are you looking for?” I asked.

“Secret passages,” he said.

“Oh!” I said, with that practiced, measured excitement I reserved for nonsense. “Have you had any luck?”

“Not here,” he said. He looked up from his task and glanced sidelong at his sister. “Virginia cried at school today,” he said. At the accusation, Virginia’s eyes welled with tears. It didn’t take much.

“Only a little,” she said, her voice on the verge of breaking.

“She told Mrs. Esker that she loved her, and Mrs. Esker said she loved all of her students equally.” Walter picked up something out of the soil and held it up.

“That’s called an arrowhead,” I said. “People who used to live here used them to hunt animals. Why did that make you cry, Virginia?”

Virginia tried to smooth Baby Barbara’s cowlick. “Be-because I wanted her to luh-love me the most,” she said. Baby Barbara looked into Virginia’s crumpled face and began to wail. I took the baby and gave Virginia a tissue from my pocket. I can’t explain it, but when she dabbed her face she looked like someone else. Like a beauty queen. Or a bride.

The back door opened and a woman with long, straight red hair emerged from the house. Her face was wide and open, like you could tell her anything at all. She held a camera in her arms the way I was holding Baby Barbara. She wasn’t filming anything, though the lens cap was missing. I saw its outline in her pocket.

“I’m Nancy,” she said. “I’m the filmmaker. They told you I was coming, right?”

I nodded.

“You’re watching the children tonight?”

I nodded again. I stared into the dark, liquid eye of the camera. It was like a well with no bottom. It was like every celestial event that wasn’t happening above us: black hole, wormhole, solar eclipse. Virginia pressed the damp, crumpled tissue back into my hand and took Baby Barbara out of my arms again. Walter found another arrowhead and dropped it with a click onto the other.

“What’s your name?” Nancy said.

I looked down at the camera. Even though she wasn’t holding it like people did, I felt nervous. Like it could see me. She followed my gaze and then set the camera down, making a show of putting the lens cap on and tilting the blinded creature toward the house.

“I’m not tricking you, I promise,” she said. “I told the Warrens I wouldn’t film you or the children intentionally. But I would like to ask you some questions, if that’s all right?”

“Yes,” I said.

“So, what’s your name?”

I told her. I told her I watched Virginia and Walter and the baby, and had since last November.

“You’re hardly more than a baby yourself, honey,” she said. The last word felt warm as a penny in the sun.

“I’m fifteen,” I said. I wasn’t; I would be fourteen in two weeks. But how would she know? I was old enough to be sent to strangers’ houses. Fifteen years old, though. They could marry.

“Can you tell me about the house?” I swallowed.

“Ed’s office is upstairs. There’s a darkroom in the basement, where Lorraine makes the photos. It’s near their collection room, where they store artifacts from their cases.” Somewhere in that room was a fingernail clipping from the guest room where my aunt had stayed; it bore her distinct shade of polish. Ed had declared it a tie to her spirit; something that had to be contained or else her torment of me would never cease. My mother asked how much it would cost to store it. No charge, Ed said.

“What about out here?”

“There’s a pond, a shed. There used to be a sandbox but it got infested with spiders so they took it away.” The grass had been dead underneath. It was still dead.

“What’s in the shed?”

“I don’t know. It’s locked.”

“It’s not for children,” said Virginia. “It’s dangerous,” said Walter.

“Do you know much about the party?” Nancy asked. “I know it’s for the comet,” I said.

“Do you know that people used to have parties when there were comets in the sky? It’s an old tradition.” She dug around in her pocket and pulled out a brooch—a soft white pearl surrounded by tiny diamonds and trailed by a shower of semiprecious stones. “People even wore comet jewelry.” She took hold of my shirt and before I could move had darted the pin through the fabric. I reached up and touched it; counted, quickly, every stone. She smiled, and the smile was genuine. Baby Barbara shrieked with delight, and I jumped; I’d forgotten the children were there.

“What can you tell me about the Warrens?” she said. I looked down at the brooch.

“It’s yours, honey.”

The back door opened, and there was Lorraine. She was dressed in a shimmery, silky dress, with a circular hairnet of stones. A comet, I realized. She was dressed like a comet. No wonder Ed loved her more than anything in this world or the next.

“The guests are going to arrive soon,” she said. “Let’s gather the children inside and we’ll send you all upstairs with a plate?”

When I called for the children, they arrived from nowhere. “Can I show you something?” Walter asked. I cleaned a streak of dirt from his forehead with my spit.

*

In the bathroom, all three Warren children splashed around in the tub. Virginia delicately washed Baby Barbara’s sparse pate with baby shampoo; Walter crashed a tin fire truck over and over into the tile. The last time he did it, Baby Barbara started; her eyes filled with tears.

“Be gentle with your sister,” I said. “You are lucky to have her.”

Walter handed me the fire truck and lifted a rubber duck into her line of sight. Barbara laughed.

“Like that,” I said. “You should always stick together. That’s what brothers and sisters do.”

Downstairs, someone took off a record and put on another.

With studied gentleness, Virginia turned her hand into a protective tiara and tipped a plastic cup over Barbara’s head. Her fine hair swelled with water.

“Miriam,” said Virginia.

“Yes, Virginia,” I said.

“Do you love me?”

“Yes, very much.”

“Do you love me the most?”

I worried a bar of soap against a washcloth and handed it wordlessly to Walter, who diligently began to clean his pits.

“I love you all the same amount but in different ways,” I said. “I think that’s what your teacher meant too. When you have many children, you can’t pick one you love the most.”

“But if you have one child, then you can.”

“Yes,” I said. “I suppose that’s true.”

Virginia contemplated this so deeply that when Barbara began to tip to the side she didn’t budge. I reached for the baby—her fat, slippery limbs made me feel like I was manhandling a raw chicken. For a moment, I imagined her descent, her tiny features under an inch of water. How easily the accident could happen. How I would have to come stay with the older children while the Warrens nursed their loss. How Ed and Lorraine would beg me to help them locate the spirit of the baby, and how when I found her (inexplicably crawling incorporeal through the rafters) they would tell my parents, Her perception. Her many gifts. We could not have gone on without her. I lifted the baby up, wrapped her in a towel. When the others climbed out of the tub, they stood there like a group of feral children emerging from a deep wilderness.

I handed them towels to wrap around their bodies. I stormed a towel around Virginia’s hair until she began to giggle.

I opened the bathroom door, checked for adults, and then began to lead them to their room.

When Ed came up the stairs, it felt inevitable, like he’d been waiting for us to emerge. I felt a twinge of annoyance; it would be hard to get them down when their beloved was nearby. Walter ran into his father’s arms. His father rubbed stray drops of water off his son’s ears.

“When you’ve gotten them to bed,” he said, “come join me in my study?”

We filed into the room like soldiers.

*

As I snapped the romper around Baby Barbara’s legs I could hear Virginia and Walter talking in hushed voices. When I turned to them, after putting the baby in her crib, they pulled apart and stared at me with purpose.

“Are you going to go to Columbia?” Virginia asked.

“I’m too young to go to college,” I said. “Are you worried I’ll leave, like Gerrie?”

“Gerrie went to Columbia.”

“The college or the country?”

Virginia was quiet. Walter climbed into his bed. “Are you going to be here tomorrow?” he asked.

“I don’t think so, honey.” I liked that word. I liked taking it from Nancy and putting it in my mouth.

“If you were going to be here tomorrow, I could show you what I found.”

“You can show me now.”

“It’s not in here,” Virginia said.

“What is it?”

“I’ll tell you,” she said. “But it’s a secret.”

I leaned down patiently, to receive her whisper. “We found a portal to the ocean.”

“Ah,” I said. “You’re using your imagination.” From downstairs, we could all hear someone switch one record for another. Then, a peal of laughter that rippled from one side of the house to the other. “When I was little,” I said, “and I had to go to bed during my parents’ parties, I would imagine that my room was the ocean and my bed was a boat and I was riding across the water and all I had was what was in my bed. Sometimes I would lie there and imagine all the sea creatures swimming below me.”

“That doesn’t make any sense,” Walter said. “Where did the ocean come from?”

I took a deep breath. I felt a thousand years old. I felt like they were my own children, and they had finally asked too many questions. Being a mother was exhausting, I thought, and even though I was thinking of myself, I imagined my own tired mother. I imagined her imagining me so still and quiet.

“It was just a game,” I said, “and now, it is time for bed.” I kissed them both on the forehead.

“I’ll check on you later,” I said. “If you’re still awake, you can show me the portal to the ocean.” They would not be awake.

“Do you promise?” said Walter. “Of course.”

They didn’t say anything else. Beneath the silence, I could hear Virginia’s compliance and Walter’s resistance, as if they were animals with their own distinct calls.

Before leaving, I checked on Baby Barbara one more time. (This is the part of the story I remember the most clearly. This is the part that one day I would tell with absolute clarity.) I leaned over her in her crib, and we held silent communion with each other. She wiggled her limbs but made no sound. There was mystery between us: a memory she would never remember, a memory I would never forget.

*

I went to the study and stood in the doorway. For a moment I felt floaty, strange. Like I was watching myself from over my own shoulder. Ed turned to me and held up the file he was shuffling through. “Some people over in Bridgeport think they have a ghost in their boathouse,” he said, almost bored. He handed me the file and it felt soft and warm as a hand. It was thick, for something he didn’t seem to be taking seriously. A long, detailed letter from the homeowner. Photos. Diagrams of some kind. “She thinks the comet is making things worse,” he said. His words, I noticed, were a little soft. Like he was trying to get his mouth around a big bite, and failing.

“Is it?” I asked.

“Maybe.” He rocked back in his chair. It bent sweet and sour against its own hinges. It could barely contain him.

“Tell me something,” he said, “that you’ve never told anyone else.”

I did not know what to say. I did not know what it was about that evening that made every adult who crossed my path ask me questions I did not want to answer. I thought of the biggest secret I knew: that my terrible aunt was gone because of me. That during her last visit she said I was a spoiled brat and an ungrateful horror and a monster with no redeeming qualities, so I stole her fingernail polish and painted it on my own nails and did a spell in the bathroom where I wished her calamity and she’d been dead within a matter of weeks. That my own parents didn’t notice the polish or the way I peeled it from my own fingernails during the funeral. That I didn’t feel guilt exactly, more comforted by the warmth of my power.

“When I was a child, I cut my mother’s hair with a pair of scissors while she was sleeping.”

Ed took a deep sip of his drink.

“That isn’t true,” he said. I do not know how he knew. “I wanted to,” I said. That was true.

“Are you in love with anyone? Do you let boys—do you know them?”

“Boys?”

“You’re not interested in boys?”

I didn’t understand the question. Boys were not interesting. “The first moment I saw Lorraine I knew I loved her. Her voice. I just knew.”

Ed reached into his pocket and pulled out the key to the locked drawer, which was where he kept the cash he used to pay me. He opened the drawer, as he had many times before. I had a peculiar thought in that moment: that a door had suddenly appeared in the air, where there’d been none before.

As the thought faded, Ed withdrew a sheet of tickets, almost like you’d see at a carnival. Each one was printed with an image of Solo 9—its distinct tail and the twinkling flare from its head.

“Destiny,” he said, “has a sound.”

I didn’t know what he was talking about. I wondered if I should go home. Ed was, I think, too drunk to take me. I thought about the walk. I thought about calling my parents. I wondered if I should curl up in the children’s room, wait for dawn to come.

“Would you like to feel good?” Ed asked. When I opened my mouth to answer, he tore one of the tickets from the others. “No, not good. Would you like to feel everything?”

He was placing the square of paper on my tongue when Nancy passed by the doorway. Ed was facing away from her; he did not see. But Nancy looked at me with an expression that I would remember into adulthood. I flooded with something. I flooded with a flood. In that moment, it’s the only word I knew.

*

Many years later—after the lawsuits were exhausted—Nancy’s documentary miniseries about the Warrens aired on television. Every week, I sat in my dark living room and invited them in, as they had once invited me.

I’d watched Nancy’s other projects over the years—seen her narrative voice roaming over stories about cults and serial murderers, animal extinction and environmental degradation, all lush shadows and finely honed darkness—and wondered if she remembered me. When I got old enough, I realized if she did, it was with the ache of pity. She did not reminisce about my insights or my opinions. She probably saw me fixed in time, altered and strange and desperate with longing. Just as I thought of her as she’d been back then, as if she had not aged one minute since our meeting. I thought about sending her my book, once, but in the post office I took the package back from the clerk and put it in the trunk of my car. I could not bear the thought of her opening it and wondering, even for a split second, who had sent her such a thing.

By the time they began advertising the series about the Warrens—the terrifying true stories behind the legendary film franchise—I’d almost started wondering if I’d imagined her there that night. But then there she was. Well, not her exactly. Not her face. But her camera. Her eyes.

I watched as the Warrens met, as they discovered their shared obsession. Their first case, then their second and third, and others too plentiful for ordinal numbers. Casting out a demon haunting a navy veteran. Relieving the pain of a ghost who refused to leave a swimming pool. Solving the mystery of a poltergeist who would lift and toss objects down an endless pit at a local quarry. Quieting a spirit that lured children away from their homes with whispers about their hearts’ desire. It was in this episode where we saw Virginia and Walter for the first time. In the next episode, the baby. Her birth had been hard, I learned from the narration. After Barbara, she could have no more children. I hadn’t realized. Lorraine had never said.

The second-to-last episode was about the party. Some of it—most of it—I remembered. I remembered it the way you remember a story you’ve heard over and over. Sometimes the camera would pass over some detail that gave me a tiny jolt of memory or nostalgia. A photo of the family on the mantel. The patterns on the dishware. The sight of the party planner’s brand of cigarette stubbed out in a saucer. Lorraine gleaming in her dress. Women with comets sewn in their teased hair.

But there were a few shots that surprised me, ones that I did not remember being taken. The first is one of Ed, his hand on my shoulder. It looks like he’s giving me instructions for taking care of the children, though of course by the time he’s talking to me the children are already in bed. He hands me something, which I put in my pocket. There’s a shot of me in the living room, my pupils dilated like a cartoon. A colleague of Ed’s—a professor of economics, or perhaps it was history—is explaining to me, with great earnestness, the properties of the Borromean knot, even though I look like I am blind and deaf and waiting for a bus. The last shot is of me and Lorraine on the front lawn. The sun is still up. The fat headphones on her ears, the sensitive organ of the machine directed into the sky. Then she lifts the headphones off her own head and puts them on mine. We listen to something we don’t yet understand. No one could have known, a talking head says in a somber voice.

When the credits began to flash across the screen, I sat there in the darkness, waiting for sensation to come back into my limbs.

In the darkened corner of the room, shadows stirred but did not come toward me. They tended to avoid the glow of the television. They were always trying to tell me something I could not hear.

How Ed filled the room! How thick his voice and soft his mustache, how handsome his problems. While Nancy was in the kitchen he touched me. We were in a room full of party people and he touched my face. He told me he gave the bears a way into the woods. He told me that there were fewer ghosts than people realized. The air was full of music but I couldn’t understand it. The words alit on top of my brain but did not go through. I saw my parents drift through, so quickly I could not catch them. (I wanted to tell them something but I didn’t know what.) I saw every ghost that filled the room in the basement, crisscrossing the room like they were performing a very elaborate dance. From across the room Lorraine saw me, tried to move toward me. But a woman in a costume like Barbarella took her hand, spun her, brought a glass to her lips. Lorraine danced with the woman. Ed danced with me. I could see the blood under their skin. I wanted it to be mine. I thought of a story I’d read in a book once, about fairies. You should not eat their bread. You should not partake of their wine.

In the middle of all of it, I saw Virginia and Walter at the top of the stairs. Virginia held the baby in her arms. They were still, like a tableau from an old story, faded on the paper. As I watched, a warm wind ran through them, ruffling the pages. Then, they were gone.

*

I don’t remember getting to the collection room. But there I was, I was among the dolls and the nuns’ habits and the statuary and costume jewelry. The space fairly hummed with an energy I could not name. I went and found the tiny glass vial that held my nail and the shellac of my aunt’s polish. In my hand it throbbed with a delicate warmth, like a mouse. I felt her then. Saw her too, forming out of the air as if she’d always been there, waiting. My aunt, my terrible aunt, come to finish the job she’d started. She floated there with her face and her mouth and opened her mouth and said something I couldn’t make out. A reminder of a promise.

From behind me, there was a sound. A step. I whirled to meet it. One of those horrible possessed dolls, I thought. But it was Nancy. She let the camera take in the room, and then made a show of turning it off, dropping it to her side. How old was she? I would know, one day, but here she simply felt like she existed somewhere else, in a land of adulthood I trudged toward every day. Her skin pulsed rhythmically, as though a song were moving under it.

“Honey,” she said. “How long has that been going on?”

I looked at her. I didn’t know what expression she could see.

“Childhood is a precious thing,” she said.

“I’m a good babysitter,” I told her. “I take care of the children.” “I mean yours,” she said. “Just because a man is a father does not mean he is a good man.”

I thought of my own father. It was hard, though. When I pictured him in my mind he shrank into the corner of the room, like he was trying to get away from me.

“We repeat our problems our whole lives,” she said. “The least you can do is try and not start those patterns early.”

I backed away from her and into an empty birdcage, which clattered to the ground. The clatter continued, and grew, and overwhelmed me. Above our heads, distantly, small animals left their burrows.

“This was one of the first cases I transcribed,” I said. “The last passenger pigeon and the last Carolina parakeet that ever existed died in the same cage in the same zoo. In Cincinnati. Only four years apart from each other. The zookeepers kept hearing them decades after they died, even though the cage was empty. They kept talking to each other. Like they had a secret.”

My stomach began to warm. I could feel it moving like an animal against the inside of me. Like a friendly outdoor cat, looping through my bones. Nancy moved toward me, like she wanted to hug me.

“Be careful,” I said. “You can’t even begin to imagine what’s in here.”

She led me up the stairs by the hand.

*

In the yard it wasn’t warm or cold; the air was the temperature of my skin. Nancy helped me sit down and handed me a glass of water. I took a sip of it and let the rest go down my face and chest. I sat there on the ocean of grass, wondering if evolving things would climb out of the flood into my lap. If they did, I would hold them. I would watch over them closely as they became who they were. I would hold onto them through their extinction. Sweet things. No one loved them like me.

I should check on the children, I thought, just before I thought again about the passenger pigeon, the Carolina parakeet. The end of their line. They were the last for so long. You can be the last long before you realize it.

Nancy was still next to me. I had forgotten she was there.

“I would let them be my parents,” I said. Somewhere, elsewhere, a door opened where there was no door.

“Do you want to help me film the comet?” she asked. I must have nodded because she turned the camera on and pointed it at the sky. She gestured toward the eyepiece. I looked through it but I did not see. I must have said this out loud because then she told me to listen instead. She slipped the headphones over my ears, and pointed the microphone at the sky, and I heard the last true thing I would ever hear.

*

I woke up, alone and cold, on the lawn. It was almost dawn. The tide had receded back. The sprinklers chit-chit-chitted around me like insects. The comet had disappeared over the horizon. The living room was dark and full of sleeping bodies.

Upstairs, the children’s room was empty. The beds were cold. The baby’s crib too. The last altered thought I had was that the baby’s crib looked like an empty rib cage, or birdcage, or both.

How do I explain it, I wondered, as I tried to find Nancy or Lorraine or Ed or anyone. How do I explain the emptiness of their beds? It wouldn’t have mattered, the policeman told my mother that afternoon, if they’d found the children sooner. They would have drowned within minutes, in the middle of the night. Old wells were dangerous things. It was good that it had been concealed in that old shed but a pity they’d found a way in. They must have been working at those loose boards for so long, creating a new entrance to defy the locked door.

But the baby, my mother said, the baby.

All of them, the policeman said. They could carry a baby. They were clever and bright. They adored each other. They adored adventure. What a tragedy, he said. They were so very loved.

*

When the school year was over, my mother took me to the grocery store and we ran into Gerrie. She was not at Columbia or in Colombia; she was a bag girl at the Kash n’ Karry. She did not seem to know who I was. I cried so hard my mother lifted me—now, fully, fourteen—into her arms and carried me into the parking lot. I did not know she still had that kind of strength. I hiccuped into her blouse.

My parents would eventually divorce. The ghost of my terrible aunt had been right. But in the car on that afternoon, as my mother buckled my seat belt like I was a child, we were still a kind of a family.

“They died alone,” I said to her.

“They died together,” she said.

I couldn’t explain it but both things were true.

__________________________________

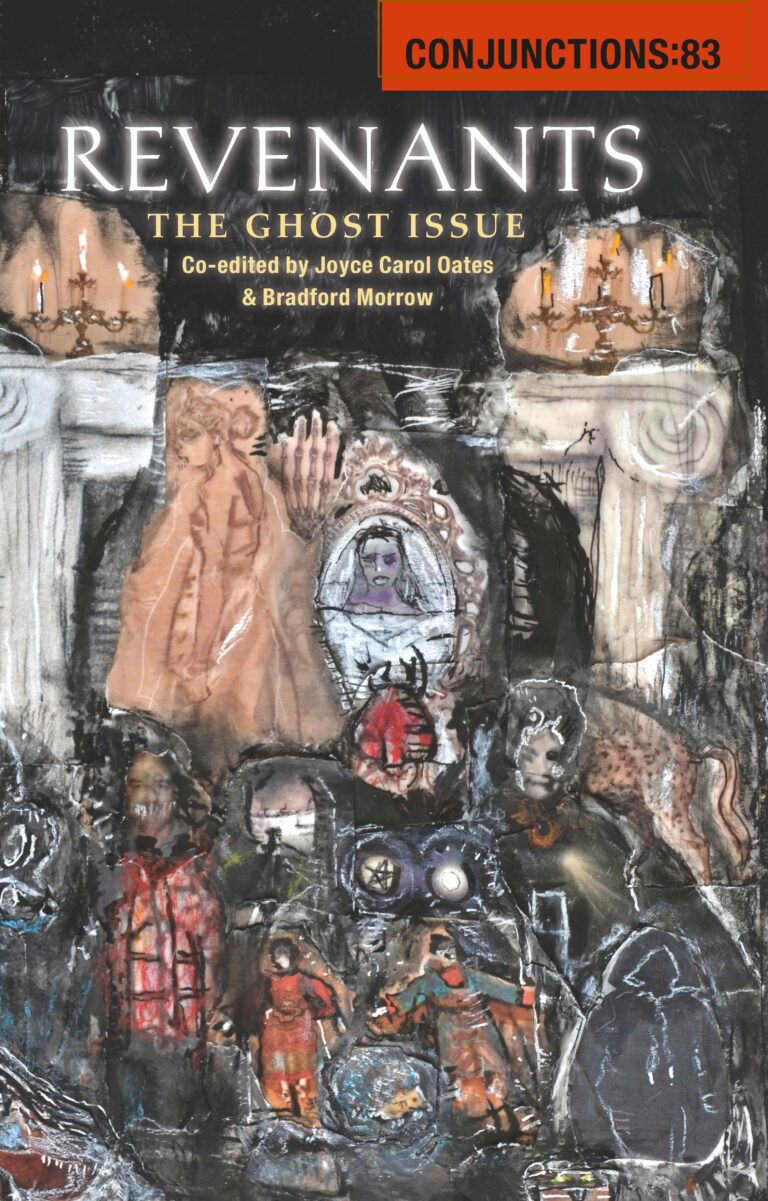

From the new issue of Conjunctions:83, Revenants, The Ghost Issue. Used with permission of Conjunctions. Copyright © 2024 by Carmen Maria Machado.