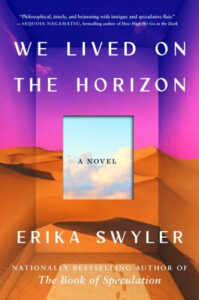

Erika Swyler on Worldbuilding as Set Design

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

As an ex-actor and former set carpenter, I’m befuddled by the book world’s preoccupation with worldbuilding, and how often it’s used to denote genre. Worldbuilding is essential to fiction, no matter what genre, as set design is to theater. Portal fantasies and literary realism both engage in worldbuilding. Black box theater and musical spectaculars both work with set design. A well-built world is a well-designed set.

Genre frequently needs its logic defined, which is perhaps why worldbuilding is often considered a genre-only concern. Within genre, there are myriad worldbuilding frameworks; fantasy alone has near endless definitions. Studying experimental theater (think black box) helped me understand that minimal set or no set is set design; it’s assuming an understanding of reality with an audience in order to expand somewhere else. Productions of Thornton Wilder’s classic Our Town favor the minimal approach because there’s a meta element—the play acknowledges it’s a play, a stage manager explains things, the audience imagines together—there may be chairs and tables, but the focus is the words and emotion. A show within a show with almost no set is a minimalist approach to a pocket universe. It relies on a shared sense of watching theater, and of Americana.

For literary fiction in contemporary or recent time periods, it’s often unnecessary to spend lengthy passages describing world forces; readers come in with real-world reference points. That’s how a concentrated novella like The Old Man and the Sea can feel larger than its size. A shack in Havana, a skiff, the sea, and a reference or two to Joe DiMaggio perfectly situate us.

Though minimalism refers to style—edited to the bone—it’s also a form of worldbuilding, one that shapes a sense of fact through directness. It’s difficult to avoid Raymond Carver when thinking about minimalism. Carver’s black box is an established understanding of 20th-century American pressures, alcoholism, infidelity, and death. His set might be a collection of furniture strewn on a lawn without explanation, as in Why Don’t You Dance? The story’s force isn’t in external pressures, complex logic, political machinations, or a perfectly drawn late 1970s America. That would demand too much space. The focus is interiority, physicality, character interaction, and questioning. From there comes world and life.

However, when worlds get strange, attention to logic, external forces, and design are essential. In set carpentry, that might mean each panel in a rotating set—one built for quick changes—needs a locking mechanism so actors won’t get walloped by spinning walls. Bad set design can kill, fortunately, bad worldbuilding only drags down a novel. It’s good to keep efficiency in mind. In We Lived on the Horizon, I’ve written a city, Bulwark, that’s also a wired consciousness. I’ve imagined Bulwark as both high tech and low tech, which demands reference points. Rickshaws easily roll through scenes, passing by panels that scan a wide array of personal data (a bit of tech that’s almost reality). I needed set pieces that were both quickly recognizable and indicators of broader circumstances.

Worldbuilding is clothing, food, and language choice—each a lock on a spinning panel. Efficiency in these choices, relying on reader knowledge and extrapolating on it, means that when diving into the unfamiliar, perhaps the inside of a giant sentient machine, there’s room for intricate set design and logic.

A production’s set design either adds or detracts. The same applies to worldbuilding.

Maximalism and the ornate also make joy. The absurdly long-running Phantom of the Opera’s elaborate sets worked overtime. Decades after first seeing it, I still recall an over-the-top set piece in an early number—an elephant with opera house workers tucked inside. This brief sight-gag was a world nested inside the main drama and did as much to build Paris as rendering the tunnels beneath.

Yet Phantom’s sets were also constricting, the actors in the elephant literally boxed in. While it would border on criminal to render Paris’s opera house without its grand stairs, when the stairs appeared on stage, they were packed with chorus members squeezed so tightly that they barely moved. It’s visually striking, and from a sound perspective, it’s the closest one could get to an operatic chorus short of being at the opera. The point was the joy of spectacle. A chandelier dropped above the audience. Sewers were created with a motorized boat, fog machines, and rows upon rows of splashy candelabras. It was a world of visual riches.

The deeper you venture into worldbuilding, the more set and logic take focus. Daniel Mason’s North Woods is a literary example of the opulent set. The novel centers on the woods of western Massachusetts and a house, both exquisitely rendered from colonization to present day. It’s centuries of history and ecology through the lens of set—imagine Phantom’s staircase singing a short story about each cast member, while singing about itself. It’s scenery as route to narrative. The woods of North Woods are the story, the characters are windows into it, and it’s an extraordinary feat. It’s worth noting that extensive worldbuilding and opulent sets often sacrifice other things. In the case of Phantom, that’s spectacle over intimacy. A reader going into North Woods searching for a central protagonist other than time, the Anthropocene period, and the woods themselves, will spend a good bit of their read lost.

The majority of novels and theater require something between the spectacle and the black box. A guiding logic or set piece is helpful for shape—in my latest novel, that’s a wall surrounding a city. The wall’s function is to speak to past horrors without subjecting the reader to hundreds of years of history. That history, relevant during drafting, is superfluous when directing reader focus. Yet not describing the wall or its workings would be asking an actor to pantomime leaning on a column rather than providing one. Even in Our Town, actors need tables and chairs. A production’s set design either adds or detracts. The same applies to worldbuilding.

Rita Chang-Eppig’s Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, lives in the sweet spot between the spare and the opulent. As a fantastical exploration of the Chinese pirate queen Shek Yeung, its readers need to have knowledge about ships and the political connections of various clans, which Chang-Eppig provides. If we’d gone into the full history of junks, or the long lineages of those in power, the book would have derailed. Precise choices about information and focus were made, resulting in a nimble set that lets the story and characters play.

When drafting, remember every bit of worldbuilding that makes it to the page—be it magic system or apartment complex—adds to the set, and stage space is limited. Is it essential history, or one too many candelabras? Even within genres, like fantasy, that allow for lengthier books, each worldbuilding addition means slightly less room for characters to move.

Conversely, when none of that work is on the page, characters do more lifting. In lieu of scenery Our Town’s stage manager renders Grover’s Corners via monologue. For myself, I like to remember rotating stages, and how they imply what a static stage often can’t—travelling long distances, passage of time, changing circumstances. Stagecraft and prose craft are conversations about creation, engagement, and the necessary. Ideally, that’s worldbuilding across all genres: designing a set that’s the best vehicle for story.

___________________________________________

We Lived on the Horizon by Erika Swyler is available now via Atria Books.