Erin Steele Isn’t Trying to Look Good in Her Memoir

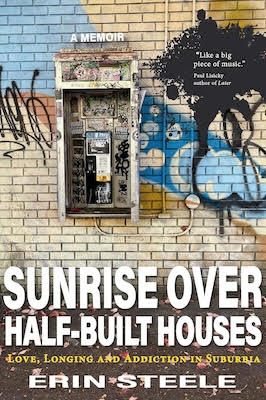

Erin Steele’s memoir, Sunrise Over Half-Built Houses: Love, Longing and Addiction in Suburbia, chronicles the life of an isolated, self-conscious Canadian teenager growing up in middle-class British Columbia to loving parents who are simultaneously present and absent. As young Erin grapples with finding connection and meaning within the suburban sprawl that eventually gives way to dark forest, we become witness to a young queer woman’s intense seeking.

Grasping for anything that might satiate her need for authentic connection, she turns to a range of complicated relationships, drugs and alcohol to find respite from her own loneliness. From the emotional manipulation of a high school classmate so involved as to necessitate police involvement, to anguished nights of self-harm, to months of disappearance, Sunrise Over Half-Built Houses asks us to sit still, listen and feel.

Within the raw honesty of her story, we become inclined to turn the gaze towards ourselves. How do any of us make meaning from the anguished creature living just below the surface of our myriads of addictions? What is it that drives our desires and needs, particularly when we are not at our best? And how can we navigate the parts of ourselves we would prefer to keep hidden? Erin brings these questions and answers to light, not through any kind of telling, but through showing us exactly how it was for her during those long years when that Pacific Northwest rain fell and fell.

It is the pervasiveness of Erin’s unrelenting search for meaning and, more specifically—a cohesive sense of self—that pulls the reader in and holds us there.

Charlie J. Stephens: Throughout the memoir, the reader is put in the position of not being able to turn away from the narrator’s reality, particularly in regards to risk-seeking behaviors. The narrator takes full responsibility for her decisions that I’m sure were difficult to face personally. The scene involving intense manipulation of a high school classmate is one that stands out. What are some of the ways you navigated those moments in writing and having the work published?

Erin Steele: Not to downplay all the self-reckoning that was required for me to put this book out into the world, but being real was simply more important than wanting to appear a certain way. We know flat characters in fiction, and memoir should be no different. Readers can feel when you’re holding back, so I resisted the temptation to scrub away what could make her (read: me) “look bad.”

Besides, the sex, drugs and music make it an engaging read, but it was always intended to be deeper than that.

Had I not faced and taken responsibility for my decisions, I wouldn’t have the perspective that elevates the book above a salacious recounting. That higher perspective is critical, showing up first in lines and short paragraphs, then growing alongside the narrator to ultimately integrate with her current reality.

It’s why one of the opening epigraphs is: “You’re every age you’ve ever been and ever will be,” author unknown.

I wanted to convey how we can get these flashes of insight, even while barrelling downhill. And although these flashes may not change anything in the present, they do exist and attract more flashes.

CS: Those flashes of insight show up in each chapter, and the narrator’s very urgent need is at the center, whether it is for love, affection, or self medication. It is easy to label this as a memoir of addiction, which of course it is, but you are able to capture the living thing underneath addiction. What are your thoughts on how this connects to capitalism and other issues of Western society?

ES: Similar to the narrator herself, there’s an insatiable quality baked into Western capitalistic society. So while it’s totally human and even necessary to want and to need, there’s a lot of power, psychology and societal conditioning behind why one might “need” a drink or drugs or chips or cheese or a cold beer or a run or a HiiT class.

An example is this: say you feel hungry. You may intellectually understand that lentils with spinach and tomatoes would best nurture your body, but you crave a Big Mac. Then you opt for that Big Mac in large part because it’s way more convenient and you’re exhausted and the dopamine receptors in your brain are obsessed with instant gratification.

There’s a lot of power, psychology and societal conditioning behind why one might ‘need’ a drink or drugs or chips or cheese or a run.

The reader experiences the narrator living out an intensely charged version of this—sacrificing basic needs like food, sleep and even her body in pursuit of what she believes will bring her fulfillment.

Whereas many Eastern schools of thought encourage turning inward, Western capitalistic society has no qualms about dangling basically everything in front of our hungry eyes with promises of satiation.

It’s a perpetual loop, and it is in this loop that the narrator is stuck. The romanticism, bright lights, feel-good drugs, sex and even music—it’s all outside her, and of course represents a firefly of happiness that cannot actually be grasped.

Truthfully, that firefly is within each of us always, but that’s not something we’re conditioned to believe in here in the colonial West, so we have to just fumble towards it on our own. That fumbling is what Sunrise over Half-Built Houses is about.

CS: A central struggle in this book is around connecting to your queerness in an environment where even basic self-acceptance was challenging. Can you speak to your current thoughts about the avenues available to isolated, queer youth in these times we find ourselves inhabiting?

ES: It is astounding to me that although my book takes place at the turn of the century, in some ways it feels as though we’ve gone backwards. That said, as horrifying as bigots on the internet can be, it’s also a place to find community. Pop culture today also embraces queer identity far better than it ever has.

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution to helping isolated youth, and society needs to shift far closer to inclusion. But these days, technology does allow people to find their people—or at least know they’re out there.

I recently sang Mayonaise by The Smashing Pumpkins (which features prominently in Sunrise over Half-Built Houses) at a karaoke night frequented in large part by late-teen and twenty-something alternative queer kids. After the line: I just want to be me; when I can, I will—which so encapsulates my character’s drive—all the queer kids randomly erupted into cheers and applause. It felt like a full-circle moment. Our people are always out there, always. Sometimes you just have to hold on.

CS: Wow, I would have just been sitting there singing along and openly weeping: I don’t think karaoke nights get better than that! How beautiful to have everything come together in that way. Speaking of music, you’ve mentioned that the Joni Mitchell lyric some turn to Jesus, some turn to heroin was the seed for this memoir. Can you comment on how it conveys the theme of seeking connection and whether you believe this holds up (or not)?

ES: Those lyrics convey what I’ve come to believe is true and what the narrator experiences in Sunrise over Half-Built Houses: we as humans may turn to seemingly drastically different things, but there’s a shared pull toward comfort and connection.

If what you turn to happens to be deemed acceptable or even revered by society, you’re privileged. But if you turn to, say, heroin, you risk being branded as a ‘moral failure.’

If what you turn to happens to be deemed acceptable by society, you’re privileged. But if you turn to, say, heroin, you’re branded as a ‘moral failure.’

What this lyric really says to me, and what I truly believe, is that we understand each other so much better than we’re often willing to accept.

Sometimes I force myself to dig down past my own disdain, and find kinship even with those whom I most disagree with. There is a simplicity in being alive and aware of it; the shared inevitability of death, the great equalizer. We all get scared and that fear manifests in so many messed up ways. In our society, it gets capitalized and politicized, then perpetuated.

I wish we could shake off all the crap that polarizes us, because that’s not the stuff that really matters. I also know that it’s not that simple. I also believe that it can be.

CS: I believe it can be also. Also I’m interested in your critique of the term “moral failure.” It’s so punitive. I read more, and the original term was “moral distress” which has a much more compassionate connotation. It was coined by ethical philosopher Andrew Jameton in 1984 and gets at the anguish caused by knowing the right thing to do, but then there are institutional or societal barriers that get in the way. It acknowledges that our choices are not always completely our own, back to your criticism of capitalism. Relating to that, throughout the memoir, there is an underlying threat of the act of being “othered” whether it is based in queerness, community, or addiction. Can you comment on how you’ve navigated “othering” within this book, as well as personally and politically?

ES: I care deeply about people stuck in cycles of drug addiction and will endlessly advocate for progressive harm-reduction measures as we figure out how to nurture the thing that causes the behaviour of addiction, which is a reaction to pain. However, when we say “addicts,” it’s easy for people to turn their heads and imagine human beings as “others.”

Yet, we all understand comfort and connection, and the absence of it. Although I label Sunrise over Half-Built Houses as a “queer coming-of-age story” and an “addictions memoir,” what it’s really about is inclusion—the antidote to othering.

When we say ‘addicts,’ it’s easy for people to turn their heads and imagine human beings as ‘others.’

I once attended a protest/counter protest with two clear “sides.” Amidst a lot of yelling and dysregulation, I witnessed two people in opposition have a conversation. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but they were taking turns speaking and really listening to each other.

That’s more of what we need—hearing each other. Then, we inevitably correct the record where it needs correcting (and indeed, it needs a lot of correcting). This is where personal stories have an integral role. Although receptivity is needed, from everyone.

CS: Memoirs provide such an intimate means to witness—and hear—each other. What are some of your favorite memoirs as of late?

ES: Some incredible memoirs I’ve read over the last few years include The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch, Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls by T Kira Madden and Later by Paul Lisicky. All three of these writers take the not-easy route of characterizing versions of themselves with blood and guts, intimately pulling readers into their respective worlds. As a reader, this is a distinction and not soon forgotten. It felt like Yuknavitch, in particular, broke the fourth wall in The Chronology of Water, which felt intimate, delightful and unique—particularly from a memoir.

I also adored It Chooses You by Miranda July and Birds Art Life by Kyo Maclear—both more avant-garde, both profound.

CS: Do you have any new writing projects in the works?

ES: Yes, I’m officially on to my second book project! It’s still early days and materializing slowly, but I can tell you that it’s literary fiction, contemporary, with a subtle touch of magical realism. I’m aiming for this one to not take ten years like Sunrise Over Half-Built Houses!

The post Erin Steele Isn’t Trying to Look Good in Her Memoir appeared first on Electric Literature.