Excerpts from The Believer: An Interview with Annie Leibovitz

“When I started working for Rolling Stone, I really thought I was doing journalism. And then I quickly realized I wasn’t, because I had a point of view.”

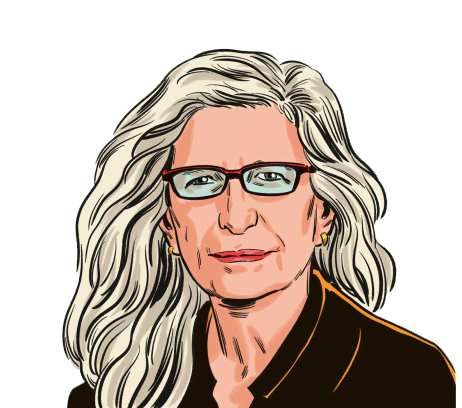

In many ways, I am an unlikely choice of interviewer for a subject like Annie Leibovitz. While I am trained as a photographer and still utilize photography across my work, for the most part I no longer author my own pictures. So I was skeptical when the call came: Were the editors of The Believer sure they wanted me for the job? Wouldn’t the magazine do better with someone more closely aligned with Leibovitz’s work—straddling the art, reportage, and editorial worlds as it does? But deep down I felt this request was tugging on my young self: As a teenager growing up in 1990s Philadelphia, I obsessively collected Leibovitz’s pictures from magazines, taping them up all over my walls, such that the walls, in fact, disappeared under their many layers. Gap ads, Rolling Stone magazine covers, and, most of all, pictures from the “Got Milk?” campaign filled my little room by the hundreds. I was, it might be noted, unaware that these were her pictures. At that point, I didn’t know anything about who made the images I was obsessed with, images I wanted to live with and inside. I had only my teenage desires to guide me. And they propelled me toward her at full tilt.

Almost three decades later, on this occasion, I miraculously got the chance to speak to Leibovitz, the person who had informed my own burgeoning photographic consciousness, curiosity, and ambition. I once heard someone say that we are all born with Beatles lyrics in our heads, so deep is their creative mark on the world. The same might be said for Leibovitz’s pictures (as evidenced by my own teenage image-collecting pursuits): she has been making this work for so many decades, and with such consistency, innovation, and panache, that it feels hard to imagine the cultural landscape without her impression.

Leibovitz grew up in Connecticut in a large Jewish family; her father was in the Air Force, and her mother was engaged in art and dance (Leibovitz herself often refers to photographing as a kind of choreography). After graduating from art school at the now-closed San Francisco Art Institute—and living on a kibbutz in Israel for several months—she quickly became the chief photographer for Rolling Stone in 1973. Leibovitz has photographed at a wild pace ever since, making some of the most iconic portraits of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: from John and Yoko in bed; to incarcerated people in Soledad State Prison hugging family members; to a young Whoopi Goldberg in a bathtub full of milk; to Demi Moore, nude and pregnant, on the cover of Vanity Fair. In addition to regularly shooting covers and features for that magazine and Vogue, Leibovitz has had exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and the National Portrait Gallery.

Our conversation unfolded over Zoom on a warm October morning (I was in the Midwest, and Leibowitz was in New York City), and after a handful of rescheduling emails. It centered on artistic process—sketching, editing, and more—while also delving into her new show at Hauser & Wirth, titled Stream of Consciousness. The show includes seventy images, from throughout her career, and largely centers creative thinkers and makers as subjects. We also discussed my work—a surprise to me!—with regard to my use of archival photography and how we relate to images in relation. We talked about Leibovitz’s decision not to publish pictures of her children, attending synagogue, camera phones, photographing Kamala Harris in the final weeks of the 2024 presidential campaign, and why she feels photojournalism is the most exciting work happening in the field.

—Carmen Winant

I. WEAK IN THE KNEES FOR HOCKNEY

THE BELIEVER: Ready to start?

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ: Let me get some water here. I just drove in at six o’clock this morning from upstate, so I’m a little bit…

BLVR: Tired?

AL: And then I had a call with these publishers; my rabbi, Rabbi [Angela] Buchdahl, needs a photograph, so it was great to have a conversation with her publishers about what they would like to do.

BLVR: What temple do you go to?

AL: Central Synagogue [in New York City]. My three daughters were all bat mitzvahed there.

BLVR: How nice—and that you are photographing your rabbi too.

AL: She is an extraordinary woman. You know, she’s Korean American, actually. Her sermons are quite extraordinary. I mean, the only reason I’m still at this synagogue is because of her. You look forward to her, to what she’s going to say. Where do you live now?

BLVR: I live in Columbus, Ohio.

AL: I read about you, and that was part of the reason I put the interview off. I went, Oh shit. She’s serious. She’s fucking serious.

BLVR: You’re giving me too much credit, I think.

AL: No, no, no. You are a serious artist, and, you know, I crawled into bed the night before and started to do my due diligence, and I called [my studio manager] Karen Mulligan. I said, “I can’t do this tomorrow morning. First of all, she’s too serious.” I mean, I think it’s interesting what you’re doing, the way you’re using photography.

BLVR: I appreciate that. I’ll carry it with me.

AL: Certainly. The older I get, and with the accumulation of the work I have, it is so interesting to see the relationships between the photographs. That’s kind of what I’m interested in in the show I’m having at Hauser & Wirth. The gallery world, it’s such a strange animal, you know?

BLVR: I have questions for you about this, so don’t get too far ahead of me! But first, I want to ask you about photographing such famous subjects. These are people that are used to being photographed; I imagine that makes your job both easier and harder. How does your process differ, if at all, from photographing noncelebrities?

AL: I mean, I’ve been doing this, what, fifty years. It started with journalism. Or what I thought was journalism. I admired the photo story, you know? When I started working for Rolling Stone, I really thought I was doing journalism. And then I quickly realized I wasn’t, because I had a point of view. I found that my work was stronger if I went with that point of view. So the work evolved. It started with these incredible years at Rolling Stone. When I look at that work, I see a young, insane, obsessed photographer. Just, you know, photographing everything in front of me, never going home, really just working all the time. It was a great school for observation and learning and becoming a better photographer. Rolling Stone and I grew up together, and eventually, with the magazine, I began learning how to photograph people. Coming from that place, it was very awkward making portraits at first, because you had an… appointment with someone. It wasn’t as fluid as just being able to be around and watching something evolve or happen.

So what happened? My subjects were sitting for photographs, and I became a little bit more inventive and conceptual. I had a whole slew of very, very conceptual years. Of course, there’s no going back after you start working like that. Now I’m kind of like a dinosaur when it comes to what I do, which is sort of a sitting portrait. I became very aware of what it is I am doing, and feel very responsible to it—to sitting photograph. I’m very interested in it and how to make it work.

As for working with people who are very, very famous and aren’t very famous, I think you’ll see, if you look through all my work, that it’s a mixture. Also, in a lot of the work, I photograph people who aren’t famous yet, and then they’re suddenly famous. When I did Whoopi Goldberg [in 1984], she was unknown. I just went to her apartment in Berkeley and photographed her there. So I’m just saying, these people sometimes become famous after the fact.

BLVR: It’s interesting: The way I set up that initial question was sort of a way to ask, What is it like to photograph famous subjects versus non-famous ones? But what I heard in your answer was a far more interesting distinction: between photojournalism and portraiture.

AL: Yes, yes. The reality is that I love photography—every part of it. There are so many ways to use photography. I mean, it’s so big. I never wanted to be pinned down to one kind of style or work. I have a huge photography book collection. I have a few photographs that I own, Robert Frank and Cartier-Bresson, and people I grew up on whose work I loved.

I just went to a Carrie Mae Weems show up at Bard [College], and I couldn’t believe it. To go through every single room and see how she used photography—it was just stunning to me to see the breadth of her ideas. I remember seeing her very early work, with the kitchen photographs [the Kitchen Table Series, 1990], and thinking, Oh my gosh, here goes art photography, whatever it is. But art photography always has been interesting, quite honestly. Hockney was the first person to do it, when he did his study on perspective. I remember being weak in the knees, thinking, That’s how the eye sees—the way he collaged his pictures together. I was so frustrated with the frame of the camera then—that everything had to be in that frame. We learned with Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank to compose in that rectangle, and to use the whole negative. But now it’s so wide open, and it’s so interesting, and it’s such a great medium. It deserves to be, and it is, now, taken seriously. It is art. It’s great to live through all that.

Read the rest of the interview over at The Believer.