“Flatten the Curve”

Anxiety was Deborah’s thing. In fact, it was her friend. Back in January, she’d been anxious about the pandemic before anyone else: she’d stockpiled the baby’s formula, and amber soaps that smelled strongly of Dettol. And when the pandemic had finally shown up, Deborah had felt a strangely pleasing sense of confirmation:

Hello. Here you are.

I’ve been waiting for you. Maybe my whole life.

It turned out the virus was—and had been, as suspected—everywhere: on the baby swing, the button at the traffic lights, on the dog come to slobber moronically over her daughter’s pristine hands.

But when the disease arrived her anxiety oddly lessened. She’d read how neurotics actually became less neurotic during the Blitz because the bombing raids only confirmed what they had suspected all along: the world is frightening; the world is bad.

And: I knew I was right about this, all along.

Never before had Deborah felt as if her vision of the world was in alignment with reality. Now she was just like everyone else. Or—ha-ha!—everyone else had the bad luck to be just like her.

That March, Deborah decided to make their house impenetrable. They only left to go into the garden, or, when the kids were really going cuckoo, Cal took them to a nearby school field. They bathed their groceries. Sprayed the post. All their friends were doing this too. Cal had had pneumonia three years ago. Men like him—late forties, fit enough—were dying in ICUs.

Despite the newness, this withdrawal also felt deeply familiar. Deborah was already an expert in declining pleasures. She could diet for months and instead of reintegrating foods she would take more out: no sugar, then no fruit; no carbs, then no alcohol. More than other people, she could deny herself nice things for longer. She found she just never wanted things as much as other people wanted things.

*

One morning Deborah took the children into the garden. She watched the baby as he poured the flowerpots onto the patio. Two lines marked where he’d wet through his nappy. The baby was loutish and oversize; nothing fit. On her phone she googled “How big is a one-year-old?” and clicked on portable children with slim waistlines. She wondered if she was bored. At first she’d been devoted to their internment, but it was weeks since she’d even put her foot outside the front door.

She heard her neighbor open his gate and soon squares of Andrei’s chestnut curls were visible through the trellised fence. He and his wife were Brazilian. He was on a work call; Andrei was something in marketing. Before lockdown Deborah had seen Andrei almost dance to avoid a dogshit on their road. He’d looked beautiful, agile.

Deborah carried his body in her mind like a souvenir. Really, she couldn’t even remember if she had genuinely found him attractive: maybe she’d made it up, now that her old life had the helpless sexy voodoo of a forgotten dream. Anyway Deborah only ever talked to Andrei from ten feet behind the shared fence, so that his breath could be ventilated away in the breeze.

She wondered if Julia and Andrei ever heard them having sex. Deborah never heard them having sex. Come to think of it, she never heard the neighbors on the other side having sex either. Deborah suspected they had a second home and were swapping between them. She thought lesbians would be more right-on but maybe that was another heteronormative way of thinking. They had hand-drawn pictures of NHS rainbows in the windows, despite the fact they had no children.

“How’s things?” Andrei said, after hanging up. “Oh, you know,” Deborah said. “On it goes.”

The baby gave her a gummy smile, and Deborah stroked his back. “How’s Joey?”

“He’s fine. Now he doesn’t even ask to go out!” “Same with Zara.”

It had been hard work, at first, separating Joey and Zara. It was like the Montagues and the Capulets! But now the kids just gazed at each other through the windows.

“We could play badminton,” Andrei said. “One day, over the fence.”

“Yeah,” Deborah said, as she traced the arc of the pathogenic shuttlecock. “That’d be nice.”

Zara wandered into the garden with her magnifying glass. Lately she’d been pretending to be a spy.

She was wearing a swimsuit, which was dangerous, since the material’s ultrasilkiness seemed to make her giddy. She was an embarrassingly sensual child, prone to erotic dancing in her bedroom window, which Joey would sometimes watch from his trampoline. Deborah wanted to tell her six-year-old to stop but didn’t know if this would make it worse. “Hi, baby,” she said, cupping Zara’s chin, resisting the urge to kiss her, since maybe all the kissing was the problem.

Zara held up the magnifying glass. “I can see you,” she said. “I can see everything.”

Next door the netted walls of the trampoline began to tremble. “Oh,” said Zara. “I didn’t know Joey was there.”

“Zara!” Joey said, his hair mushrooming at the apex of his jump. “ZARA!”

“Do you want a dozen eggs?” Andrei said. “I have several pallets of eggs.”

“I’m here! I’m here!” shouted Joey.

“No,” Deborah said to Andrei. “Thanks.”

“Don’t go, Zara! Don’t go!”

But Zara giggled and wandered off inside, and the baby pulled a plant from the soil, and Deborah thought of expensive hotels, clean and sexy, without history.

*

The weather that April took on a peculiar LA clarity: nothing but blue enameled skies, endless brightness, hot rooms with little mystery. She sensed Cal was bored too, though he was enduring house arrest better: he’d found an exercise regime, the garden bloomed, he spent more time with the kids. The more he flourished—tonally, physically, spiritually—the more it nettled her.

Deborah worked in contract HR. At the start of lockdown her company had been accommodating of her flexible working request, but recently they had tired of it and had asked her to come back full time. Now, she and Cal swapped work and childcare in a terrible cascade of two-hour shifts. Someone was almost constantly trying to put the baby down for a nap.

She thought she would be able to endure this for months, but already she was beginning to fray. Honestly, she’d had her fill of joy and togetherness, and was done with all that. The problem was the autocycle of cleaning, cooking, and caring. The problem was the lack of change: the next calendarless day, there was still nothing to do, even while the sky burnt, a blue tub.

*

Without a haircut, there was a new density to Cal’s beard; he’d started to oil it with clove. He had long hair and dark shamanic eyes. Often people thought he was Arabic. In the sunshine he’d tanned deeply, and his hands had grown rough from gardening. He looked better than ever, but Deborah felt her attraction to him lessen. A friend said she loved lockdown because she and her husband could fuck over their lunch break. Cal and Deborah weren’t doing much fucking. But neither were Julia and Andrei, or the lesbians, who’d mysteriously come back.

“Nine hundred and thirty-one people died yesterday,” Deborah said, over dinner one night. Every evening she told Cal the daily body count.

Deborah always watched the news, because it gunned her toward the fact that they were doing all this for a moral purpose. When she watched the broadcast bar charts she willed herself to grieve for the dead, but it was hard to hold twenty, thirty, forty thousand people in her mind at once. She imagined the dead in buses, in concert halls, in stadia. She felt bad about this too: she wanted to be more horrified, but the more she tried to conceptualize the dead the bigger the metaphor she had to reach for, and the more impossible they were to imagine.

Deborah looked at her dinner: roast leeks, cauliflower, rice. She knew, then, that the vegetables just could not rise to what was needed of them.

Cal was vegan. There was little that could be done about that either.

A sound came from the sky. They hadn’t heard a plane in a while. They lived in the city, but the city was stricken, subdued.

“Do you think the best thing to do is just lie down and take it?”

“Take what?” said Cal.

“Like, stop militating? Be more Buddhist, accept surrender: that wanting things only leads to grief. Etcetera?”

Cal looked at her blankly. “What is it that you want?”

“I don’t know,” she admitted, though she thought: not this.

They didn’t speak for a while as Cal checked WhatsApp. She herself didn’t look at her phone at the table. And anyway, she hated WhatsApp. The constant messages made her feel under siege.

“I spoke to Satomi yesterday,” Deborah said. “She told her husband: ‘Give me the virus! Put it in my veins! I cannot spend another minute with my children!’”

“Isn’t Satomi Buddhist?”

“I don’t know. She might be.”

They carried on eating. They’d used food against the tedium, and now she felt softer, inflated. Deborah looked around the dining room. They’d only just bought their house, and she wondered if it would be renewable, or if it would always remind them of this year’s terror and lassitude. She knew they were the lucky ones: a bedroom for each child, a garden, but reminding herself of her luck didn’t help raise the shelf of her mood. “All of this. Why doesn’t it seem relative? All that shit, I mean”—her voice gathered reverb—“the makeshift morgues, the tiny funerals, why doesn’t all that”—she gestured to the window—“not make this more bearable?”

“This is hard.”

“I always thought I was the queen of this. Endurance.” She thought it would be the same as quitting cigarettes, sugar, booze. “Turns out, I don’t think I am. I’m actually intensely fragile. Weak.”

Cal pulled her onto his lap. She touched his beard and its Death-Star blackness. He was so handsome. She loved him, and yet wanted more of him. It seemed like he was going to say more, but the baby cried out, and instead Deborah went to him.

Upstairs she soothed him easily. He didn’t fight her, and so nothing of the moment had its usual ambivalence. She kissed him while he slept, kissed him so many times she risked waking him, until she persuaded herself to put him back in the cot.

She peeked around the curtain. The window was open, and she saw Andrei, on a call again, speaking Portuguese. She wondered about the type of woman with whom he would have an affair. He looked up at her and smiled.

She put her finger to her lips.

Andrei made a “mea culpa” gesture, sneaking off to the shed, though she hadn’t meant to tell him off. Downstairs she heard Cal doing the dishes while watching skate videos on his phone; she could hear the flame-like crackle of the opening credits, and then the grind of wheels. Sometimes, in the evenings, all they could do was commune with their phones. They wasted the evenings because they had no energy for

them. In the evenings they were done for.

The breeze sucked the blind in and shot the room with light; that must have been what roused the baby. Deborah thought of the time she’d flown fourteen hours, Tokyo to London, and the light from the cabin window had been an endless afternoon. Yes; this drift, this waiting, this negligent eating.

__________________________________

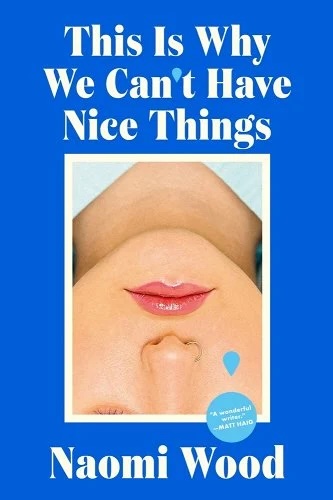

Excerpted from “Flatten the Curve,” This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things by Naomi Wood. Reprinted with permission from Mariner Books, HarperCollins Publishers. © 2024 by Naomi Wood.