From Princely Regalia to Women’s Underwear: The Evolution of the Color Pink

He was a prince whom all of Europe nicknamed “the pink prince” (der rosarote Prinz): Charles Joseph de Ligne (1735–1814), marshal of the army of the Holy Roman Empire, diplomat, thinker, writer, scholar, and a great ladies’ man.

His courtly manner, wit, elegance, and gaiety charmed all the European courts. His nickname came from the traditional livery of his house along with his personal taste for pink, notably in clothing and furnishings, but also from his optimism and good humor. Hence we have proof that in the late seventeenth century, the color pink, symbolically, already evoked joie de vivre, pleasure, and lightheartedness, a pink that was not pale and delicate, but strong and saturated, closer to a light, vivid red.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Charles Claude de Flahaut, Comte d’Angiviller, 1763, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Charles Claude de Flahaut, Comte d’Angiviller, 1763, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The example of the prince of Ligne remains the exception, however, and comes somewhat late. During the French Revolution, masculine pink was clearly less common, and in the first years of the nineteenth century, pink became almost exclusively feminine. Around 1820, in the midst of Romantic ferment, men no longer wore pink except for shock value. Nevertheless, this was not a matter of the color signaling masculine homosexuality.

Here again, it would be anachronistic to see a sign of homosexuality or effeminate behavior in the wearing of pink by men in the second half of the eighteenth century or first years of the nineteenth century. Furthermore, it would be absurd. The prince of Ligne himself, who happily wore this color for many decades, had sixteen children by his wife and multiple affairs with women throughout Europe. All women found him charming. In 1808, when he was seventy-three years old and hosted Germaine de Staël at his home in Vienna, she wrote to her dear friend Juliette Récamier, “This man, the nicest man on earth, treats me like a daughter. Like his daughter . . . , alas!”

In addition, with the end of the ancien régime along with the disappearance or transformation of life at court, men’s use of makeup and powder declined. It was still the custom in France at the end of Louis XV’s reign, yet less so during the following reign. Elsewhere in Europe, notably in Protestant countries, men rarely wore powder and makeup.

Gradually makeup once again became the business of women. In the same period, the dramatic reds women used excessively in the mid-eighteenth century became more discreet, giving way to more delicate tones on cheeks and lips, in keeping with the new codes of society. Pinks—all pinks—held a place of honor and would continue to do so for a long time. Of course, red did not disappear from makeup practices, but it was limited to the lips alone, at least among those who were then called “honest women.”

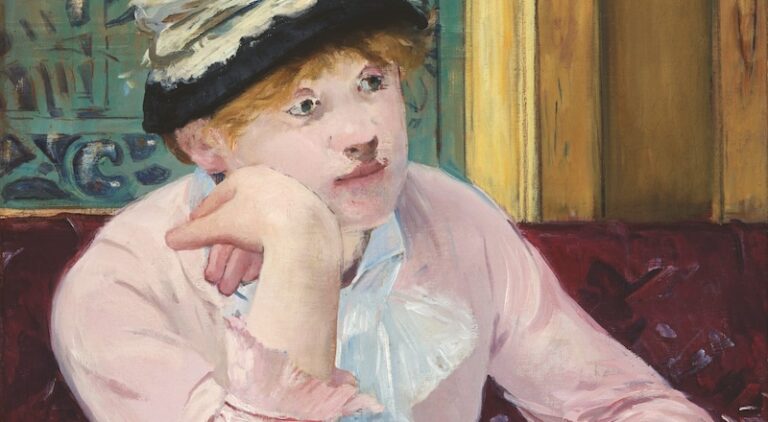

Beginning in the years 1860 to 1880 and until World War II, only those women who made a profession of debauchery and a few who wanted to make a scene continued to paint their faces red. Many great painters, fascinated by those living at the margins of the social order, left us some famous images of them. These include Édouard Manet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Kees van Dongen, Amedeo Modigliani, Otto Dix, and others. Women of polite society were more discreet, but did not give up using red for the lips. In fact, after World War I, its use became more democratic, and lipstick became an object of true mass consumption. Now sold in tubes with a turning mechanism, it was available in a great many shades. These were given names having less and less to do with the color, whether it was red or pink.

In the past, words like cherry, strawberry, or poppy, perhaps accompanied by a simple adjective (light, dark, matte, or glossy), sufficed. Now red shades were designated by phrases meant to be poetic or catchy, without the least attempt to name the precise color, but rather to surprise, intrigue, or conjure dreams: Morning Peony, Andrinople Beauty, Midsummer Night, and Opera Festival. Brands competed in their inventiveness, captivating women not only with the vast array of shades and the quality of their new products but also with the originality of their names. At the same time, many makeup testers were made available to serve as guides or for advertising. They constituted veritable little lexicons of red and pink; no other color, in any other domain, offered anything like this.

Édouard Manet, La Prune, 1877 ou 1878. Washington, National Gallery of Art. © Bridgeman Images.

Édouard Manet, La Prune, 1877 ou 1878. Washington, National Gallery of Art. © Bridgeman Images.

But let us go back once more to the moment when the fashion for romantic pink was in decline, and then displaced and transgressed. Following that, in the second half of the nineteenth century, came a certain discrediting of the color in clothing as in furnishings and the decorative arts. Pink became sentimental, petit bourgeois, and old-fashioned, if not insipid. Elegant ladies in high society henceforth relegated it to women of the middle classes, or even to shopgirls and lowly seamstresses. As for men, they mistakenly believed this color to still be in fashion when it had long been passé, or they complacently saw the future as rosy when dark days lay ahead. About 1900, many authors turned to irony in the face of so much naivete or foolishness:

The bourgeois man must have pink, that is his color. His daughters dress in pink and so does his wife, until she is over sixty. He himself is rosy and joyful as a young pig when business is good. He insists on seeing everything through rose-colored glasses and wants everything to be in the pink…………………………. Following so many poets, he alone still dares to speak of “the rosy fingers of dawn.”

This discrediting of pink explains why, at the turn of the century, it starts to be hidden, passing from women’s outer garments to their undergarments. The first half of the twentieth century was indeed the time of pink underclothes, and not an enticing or exciting pink but instead a discreet, dull, slightly beige pink meant to more or less evoke the color of Caucasian skin tones. Corsets, pantalets, stockings, garters, and then, later, underpants, slips, and bras increasingly adopted this distinctly unseductive but serviceable shade, abandoning white to young women of the upper class and red and black to professional women prostitutes.

Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, this beige pink gave way to pastel shades of different colors (sky blue, pale yellow, and sea green), before white made its big return, followed by that of more vivid colors. Today, according to statistics, it is black that prevails. Not only is there absolutely nothing erotic or provocative about it, but for synthetic fabrics, it is the color that stands up longest to repeated machine washings.

_____________________________________________

From Pink: The History of a Color by Michel Pastoureau. Copyright © 2025. Available from Princeton University Press.