From the Wakefield Twins to Claudia Kishi: How We See and Don’t See Ourselves in What We Read

My early reading journey pulled me away from my parents and culture, until one day, it brought us back together and into the story.

I have a dreamlike memory of a time, before I gained the power to read and write, when my parents would speak to me in Mandarin. This wasn’t the language popularized in movies and shows, the harsh guttural consonants and painful twangy vowels. No, the language I first remember was soft and sweet, melodious coos and soothing reassurances that would forever remind me of safety and home.

Not long after I grew accustomed to this comforting language—this linguistic security blanket—it was stripped away. My parents decided it was crucial for me and my younger brother to speak flawless English with not even a trace of an accent. They were convinced this would be the key to our eventual membership in this new English-speaking world. Our acceptance.

I was too enthralled by the Wakefield twins and their world to realize how much these books were “othering” me in my own mind.

Our belonging.

We never discussed what pushed them to this conclusion, whether it was the lack of diversity in our community, or whether it was the times people shouted at my parents to learn English or yelled at all of us to “go back to China.” (“Is she going to buy my plane ticket?” I remember my dad’s friend muttering in response.)

Whatever the reason, from then on, my parents refused to speak to me or my brother in Mandarin. They enrolled us in public speaking and acting classes at the nearby college, which we attended weekly. The only problem was—as I grew older and perfected my spoken English, and as I read hungrily and fell in love with writing, reading, and all parts of the English language—I drifted further and further from my parents, leaving them behind on their own linguistic island.

The first set of chapter books I remember owning was a nine-book starter pack from the Sweet Valley Twins series, a middle grade spinoff of the young adult series Sweet Valley High. My mom had purchased these books for me through the Scholastic Book Fair order form when I was seven, ticking the little boxes and returning the form in my backpack with a crumpled check. How did she select these from the sea of English-language books that must have been as foreign to her as cold weather and Western food? Was it the twinkle of happiness and security in the pretty twins’ eyes as they stared out from the covers? Was it the image of these well-adjusted American girls who, no matter what they did, always belonged?

I read these books one quiet afternoon, curled up on the couch, the books in an orderly pile at my feet. “Read” is probably the wrong word. I consumed them, inhaling and absorbing them as thoroughly as I could. I was riveted by this foreign world filled with beautiful Californian kids and their witty parents who always cracked the right jokes. I followed along hungrily, safe in the knowledge that no matter what scrapes and misadventures the twins fell into, they would always come out as winners.

The Wakefield twins were flawless, in appearance and mannerisms. To the extent they had weaknesses, those weaknesses were charming and benign (“oh no! Jessica can be disorganized, and Elizabeth studies too much!”). Even now, I can recall some of the opening lines that appeared in every book, always introducing the girls by appearance first: “slender, with silky blond hair and eyes the blue-green of the Pacific Ocean.”

I was too enthralled by the Wakefield twins and their world to realize how much these books were “othering” me in my own mind. It never occurred to my seven-year-old self to notice the lack of diversity among the characters. To wonder why there wasn’t a single Asian character, despite being set in Southern California.

It’s possible I didn’t notice the lack of diversity because it mirrored what I was experiencing in my predominantly white neighborhood. As the only Asian girl in my grade for most of my elementary school years, and then one of only three Asian girls in my grade during middle school, I had grown used to the strange dichotomy of staring at a sea of white faces only to be shocked when I glanced in the mirror and was confronted by my own Asian features. My three best friends, all of whom had names that started with “J” (Jaime, Jessica, and Jennifer), had the same blond hair and blue-green eyes as the Wakefield twins.

As I got older, I expanded my reading selection and discovered fascinating stories of other worlds that existed outside of Sweet Valley (the sisterhood in Little Women, the swashbuckling adventures in The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle, the existential crisis in Tuck Everlasting, and the survival story in Homecoming), but Sweet Valley Twins was like a comfort food I returned to whenever I needed a literary hug. I could never imagine myself in their world—where would I fit in?—but that was okay. It was enough to be a spectator.

Except something strange started to happen. As I returned to these books over time, I also began to notice my parents’ broken English and lilting Chinese accents more and more. They weren’t like the parents of the Wakefield twins in Sweet Valley, the ones who joked with their kids’ friends and fit in so perfectly. My parents spoke to me in their own brand of English, but it wasn’t long before I was translating for them—idioms, slang, nuanced expressions. As I drew close to my teen years, during a time when communication between parents and kids is complex enough, I found myself dealing with an additional linguistic barrier, and I resented it.

The worst was when we argued. When they became flustered and emotional, their English faltered even more severely. Hearing their misspoken words made me feel so helplessly angry—why were we such foreigners in this place where I was born and should have comfortably belonged? Why couldn’t our family be insiders, our communication frictionless, like the families in Sweet Valley?

I was desperate to fit in. Now I believed, as my parents had, that my English fluency was my membership card. My best friend once called me on the phone with her friend, a girl I had never met named Jackie (another “J” name). We chatted amiably, and a few days later, I met Jackie in person. My best friend told me later that Jackie said, in a voice full of awe, “I didn’t realize she was Asian! From her voice on the phone, I thought she was from here.” I knew what she meant—she had thought I was white.

Far from feeling offended, the words sparked a glow of pride, and I rushed home to record the comment in my diary, verbatim and underlined. I was starved of acceptance and willing to devour even the crumbs of inclusion. I was also aware that admission to this new club did not extend to my parents, and the unfairness of it broke my heart.

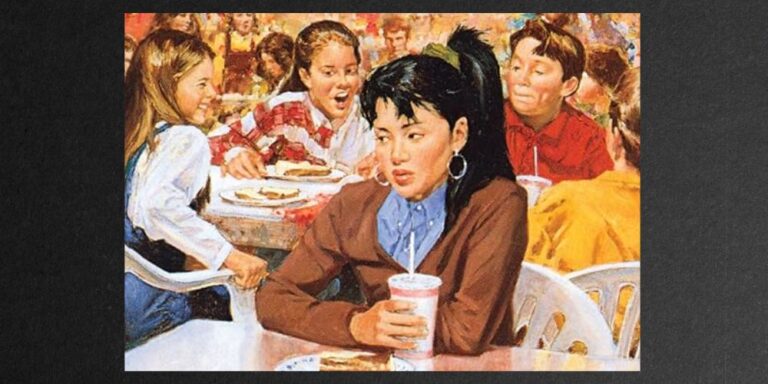

My journey to understanding my parents was also facilitated by characters like Claudia Kishi and books like The Babysitters Club.

Then, at some point, I was introduced to another middle grade book series: The Babysitters Club. The cast of characters in the Babysitters Club was as diverse as Sweet Valley was homogeneous. One of the characters—Claudia Kishi—was nothing short of a groundbreaking revelation to me. A Japanese-American girl living in Connecticut, she was popular, fashionable, artistic, loved junk food, and struggled with math. She shattered every existing Asian stereotype I had come across.

More importantly, she spoke flawless, unaccented English as her first language, and she had immigrant parents who spoke broken English as their second. She normalized Asian individuality and Asian family dynamics. In her, I finally saw someone like me existing as part of the story.

Claudia, and the portrayal of her family, helped spark an epiphany about my own parents. Their broken, flawed, accented English—the English I’d always chafed against—that was their additional language. They could speak two languages when I could only speak one. I began to speak to them—really speak to them, beyond everyday discussions about homework and chores, and I learned they had arrived in America with one suitcase and no real friends or connections in order to build a new life for us. They endured freezing cold weather and freezing cold discrimination, and they fought against language barriers as they worked to create a life completely separate from their families and the only home they had known. They could not have imagined all that effort and sacrifice would result in their daughter one day looking down on their English.

It can be so jarring to read books where no one looks like you, and no family resembles your own. Claudia Kishi changed things—she showed me there was a world beyond Sweet Valley.

Part of my newfound understanding and admiration for my parents was driven by simply growing up, moving out of the egocentric childhood phase and seeing things from other points of view. However, my journey to understanding my parents was also facilitated by characters like Claudia Kishi and books like The Babysitters Club. The ability to find a character like me, with a family like mine, truly opened my mind. Seeing someone who was living my experience was so inspirational. It validated the idea that I—and my parents—could also be part of the story.

__________________________________

Kaya of the Ocean by Gloria L. Huang is available from Holiday House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.