George Orwell’s Doublethink: How Much Can—Or Should—We Know About Our Literary Idols?

“He felt as though he were wandering in the forests of the sea bottom, lost in a monstrous world where he himself was the monster.”

–George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

*

Craig and I are at our son’s third-grade parent-teacher interview. We sit on the miniature chairs, our knees just fitting under the laminex desks. The classroom is festooned with pictures, paintings, geography and maths projects, hanging from every wall and pegged on strings crisscrossing the air above us. But the central sign hangs in pride of place off the teacher’s desk. From my perch on the low chair it is exactly at eye level, and it is what nine-year-olds most need to know, possibly what we all most need to know: “INTEGRITY: Doing the right thing even when no one is looking.” Eileen O’Shaughnessy, George Orwell’s wife, called it ‘honesty.’ Orwell called it ‘decency.’

And in that moment I see how the concepts of privacy and decency, so fundamental to Orwell, can be opposites in patriarchy. In the privacy of his own home at that time a man was legally entitled to behave in ways that would not be considered decent (or legal) outside it, that would be an affront to his own sense of integrity if he behaved that way to anyone else. He can behave that way, in fact, to women in or out of the home because our silence (enforced, traditionally, by shame) guarantees his privacy.

Doublethink is so effective men can be bewildered by this vast world, invisible to them, which has upheld them.

How can a society live with a concept as contradictory as the decency of the unaccountable private patriarch at its heart? Orwell said it best:

DOUBLETHINK means the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them…The process has to be conscious, or it would not be carried out with sufficient precision, but it also has to be unconscious, or it would bring with it a feeling of falsity and hence of guilt…it is a vast system of mental cheating.

Patriarchy is the doublethink that allows an apparently ‘decent’ man to behave badly to women, in the same way as colonialism and racism are the systems that allow apparently ‘decent’ people to do unspeakable things to other people. In order for men to do their deeds and be innocent of them at the same time, women must be human—but not fully so, or a “sense of falsity and hence of guilt” would set in. So women are said to have the same human rights as men, but our lesser amounts of time and money and status and safety tell us we do not. Women, too must keep two contradictory things in our heads at all times: I am human, but I am also less than human. Our lived experience makes a lie of the rhetoric of the world. We live on the dark side of Doublethink.

Doublethink is so effective men can be bewildered by this vast world, invisible to them, which has upheld them. And so women are more equal than others, when it comes to recognizing it.

How is it Orwell comes to see the world as split between decent and indecent, conscious and unconscious? Perhaps his ability to see both sides comes from experiencing splits in his own life. He passes as posh at Eton, though he’s an outsider noticing the tics and traits of a class he’s not born to. He goes to Burma to enforce colonial rule in a rapacious racist system, but he comes from a mixed-race French/English/Burmese family himself. He chases woman after woman and is homophobic to a degree his friends find remarkable, though his desire, hidden perhaps from himself, may have been for men. Living a split life enables him to see reality as a cover story and go looking for the other one. But it makes it harder to think of himself as the same inside and out or, as he put it, ‘decent.’

We want people to be ‘decent’ and we want our writers to be too. Orwell engaged with this question of good work coming from flawed people. Does it also require doublethink to admire the work and ignore the behavior of the private man? The question arises for him thinking about Dalí, Dickens and Shakespeare—and, tellingly, how they treated their wives. Reading Dalí’s flamboyant autobiography, Orwell calls him a “dirty little scoundrel” who “boasts that he is not homosexual, but otherwise he seems to have as good an outfit of perversions as anyone could wish for.” Orwell is gruesomely appalled by Dalí’s necrophiliac urges, his fascination with excrement and his sadism to his wife. But Dalí, he thinks, is also a great artist. How can he hold these two things in mind at the same time?

In an essay on Dickens, Orwell argues explicitly that an author’s mistreatment of a woman in private life should not affect how we read his work. He dismisses a novel about Dickens as “a merely personal attack; concerned for the most part with Dickens’s treatment of his wife.” “It dealt,” he writes, “with incidents which not one in a thousand of Dickens’s readers would ever hear about,”—nor should they, he implies—”and which no more invalidates his work than the second-best bed invalidates Hamlet.” (Shakespeare willed his ‘second-best bed’ to his wife, a fact which has spawned centuries of agonized—and inconclusive—examination of whether it was an act of testamentary bastardry or something else.)

For Orwell, it is possible to think of Dickens completely separately from his work because “a writer’s literary personality has little or nothing to do with his private character.” A man should be free to write as if he were one person, and behave like someone else altogether. What happens to the woman in the huis clos of his privacy doesn’t count.

Which leaves completely open the question of how much the dark furnace inside Orwell—inside any of us—is the place from which the work comes. No great artwork feels as though its author is unacquainted with this place. After all, it is the invisible world we want art to show us.

But it is a world in which you might be the monster. “The point is,” Orwell writes of Dalí, “that you have here a direct, unmistakable assault on sanity and decency…in his outlook, his character, the bedrock decency of a human being does not exist.”

For Orwell, human decency is the ultimate test of a person. Decency is what will save us from totalitarian and other cruel instincts. It is the quality in the animals of Animal Farm and in the ‘proles’ of Nineteen Eighty-Four that provides the only glimmer of hope. But is it real, or a manhole cover on another life?

Sometimes, as I sign books for people after an event, I channel the novelist Richard Ford. I once heard him explain why he feels he is always, inevitably, a disappointment to readers when they meet him. “I put my best self into my work,” he said, opening out his hands, “and I am not my best work.” In the gap between his hands I saw the gap between an author and their work. This is not an empty space. It’s full of dark matter, matter that holds together the writer, the work and the reader.

Signing queues are a chasm of intimacy. People, not at all unreasonably, would like you to be the person they think you are from your work. You can see in their kind, open faces that these total strangers already know you, as the person they have intuited on the basis of the book. In the intimate, imaginative fusing that is reading they will have brought a lot of themselves to her. So the ‘you’ they want you to be is a hybrid, an amalgam of you both.

Writers pull from themselves things they know and things they don’t, and put them out there for the world to see. At a book signing you are being asked to be worthy of the work you have written by matching yourself to a reader’s imagined version of you, as if you are a key meant to fit into a lock-shaped space in someone else’s mind. If it fits, you will be the guarantee that authenticates the work. And if it doesn’t (I mean, if I don’t), what then?

Any writer could fall into the gap between what a reader imagines of them, and who they think they are. And a woman might live there.

These anxieties of authenticity exist because when words go inside a reader, they make magic. They fizz and pop and conjure. They change minds. Your words may cast a spell on the reader but they cannot be felt to be a con-artist’s trick, for then the reader will feel defrauded. All the reader wants is for the avatar sitting behind the table to match their inner picture. It’s not much to ask, surely—and there they are, standing shyly, patiently, expectantly in line, book in hand, sticky-note marking the spot to sign the deal.

But on the page, as Virginia Woolf put it, “‘I’ is only a convenient term for somebody who has no real being.” That written ‘I’ is flexibly, creatively capacious, outrageous, furious. She evades gender expectations. She owes no one anything. She is not managing the Household List; she is not worried she’ll hurt her husband, or offend her friends, or neglect or shame her children. She is not, in Woolf ’s words, “harassed and distracted with hates and grievances,” legitimate and important as those might be.

That inner ‘I’ is both known and unknown to a writer. She may be similar to the one psychoanalysis tries to recover—remembered or created on the page or in the consulting room. Like the force behind crop circles or the tides, the self leaves traces in other phenomena—our dreams, our writing, our children—but remains out of sight. None of us is who we think we are. None of us may be ‘decent.’

To my mind, a person is not their work, just where it came from. To want the two to be the same, on pain of ‘cancellation,’ is a new kind of tyranny. And from there, no art comes.

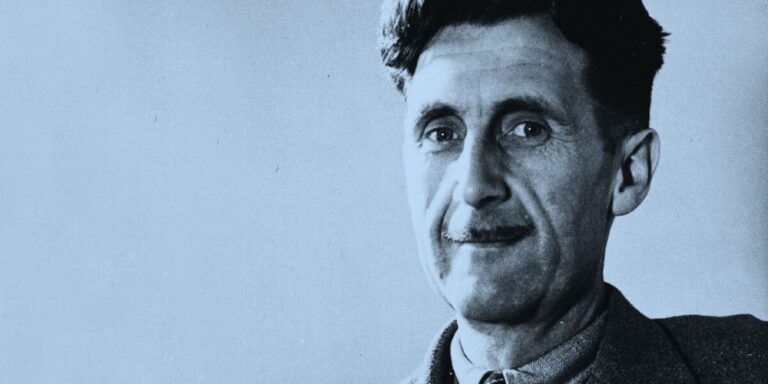

If Orwell were sitting behind a table signing books today, a fan in the queue would see the man they know from the work, who is the man they want to see: a skinny fellow in an ancient, battered sports jacket too short for his arms, chain-smoking roll-ups and coughing, acute blue eyes, high-pitched Etonian drawl, a bit of a stutter. They would see the grand wizard of plainspeaking, of decency, of the underdog. They would see a self-deprecating man who investigated the lives of the poor, who risked his own life to fight fascists in Spain, and who denounced hypocrisy in essay after brilliant essay. A sympathetic mensch who, clearly, from the look of him, had no thought for himself.

And then, if you were a young woman, standing shyly, patiently, expectantly in line, he might ask you, if you could spare the time, though of course you probably have better things to do—cough, cough—to go for a walk in the woods.

Any writer could fall into the gap between what a reader imagines of them, and who they think they are. And a woman might live there.

__________________________________

Adapted from Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder. Copyright © 2023 by Anna Funder. Excerpted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Audio excerpted with permission of Penguin Random House Audio from Wifedom by Anna Funder, read by Arianwen Parkes-Lockwood and Jane Slavin. © Anna Funder ℗ 2023 Penguin Random House, LLC.