George Saunders on Denial and the End

First Draft: A Dialogue of Writing is a weekly show featuring in-depth interviews with fiction, nonfiction, essay writers, and poets, highlighting the voices of writers as they discuss their work, their craft, and the literary arts. Hosted by Mitzi Rapkin, First Draft celebrates creative writing and the individuals who are dedicated to bringing their carefully chosen words to print as well as the impact writers have on the world we live in.

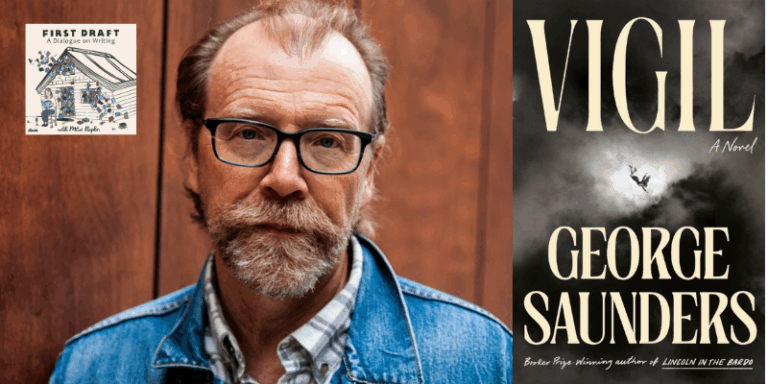

In this episode, Mitzi talks to George Saunders about his new novel, Vigil.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

From the episode:

Mitzi Rapkin: There’s several big questions that your novel asks and leaves a reader with. One that I thought about a lot is for someone like your main character, the oil executive, KJ Boone, who was so powerful and basically could do whatever he wanted, he could manipulate science. And at the end, no matter how strong you are, of course you don’t always get to choose your death experience. For instance, your other character Jill was blown up. She didn’t have time to think about her life. She couldn’t have had the benefit of someone like her [an angel] coming to her. But KJ Boone has the benefit of that. And at the end, because he has a brain tumor, he thinks about how his body is reduced and people are changing his diapers, and he’s just weak. In a death like this, you are just reduced to a body, in a way. And I guess it is our choice what we want to do with a spiritual side to our lives and to our deaths. We don’t have to embrace it. And denial is a choice. And I’m just curious about that big question in the book.

George Saunders: It’s a big one. And I mean my instinct is that, you know, we all have that fantasy of the good death, you know, like you just gather everyone around you, and then just smile and thank everybody and then, boom, you’re gone. But I don’t think that happens all that often from what I can anecdotally hear. I know when I have a flu, I’m a big pain in the ass, you know, like, I mean, all my high-minded ideas are just gone, you know, I’m just a big whining baby. So, I’m guessing that even that part of it is not in your control. But that might be I’m guessing why you would want to have a spiritual life, because then when you get into that position you’ve got some foundations or maybe habits of clear thought or positive thought, or whatever your spiritual life gives you. It’s sort of like if someone said, you have to run a marathon. I’m like, okay, I’ll figure out when I get there. Okay, but you know, you’re going to be hurting by mile two, whereas if you trained your whole life, then you could do it. So, I think that’s the thing. And with Boone, I think one of the late revel revelations of the book was that he had, really – he’s a very powerful guy with very strong mental habits – and so, you know, I thought, Well, was there ever in the history of mankind, has there ever been someone whose habits of denial and self-reification are so powerful that they don’t relent even at the moment of death? And I’m like, well, yeah, I’m sure that happens all the time, you know, or somebody who got through their life with a certain set of ideas, some of which might not be true, but they really believed them. And I could certainly see that in that we can state you might double down, you know. Part of the fun of a book like this, is that there are precedent books, you know, like A Christmas Carol and some Tolstoy stories, Master and Man and The Death of Ivan Ilyich. And those books lay out certain possibilities of in those three cases of redemption. But I was kind of thinking, well, there must be some version of Scrooge that doesn’t take the bait, you know, some version of Scrooge who’s even more damaged and hurt than Scrooge, the Scrooge that we know. And that guy’s like, no, fuck you. I’m not being changed. So, that was just one of the possibilities I wanted to leave open. And then, of course, the way you figure out that is to just write the book, you know, and revise, revise, revise. And then by the time you get to that moment, you know him really well and you don’t want him to do something out of character, because that would be a cheap shot. So, the beauty of writing is that you try to tell the truth all the way up to page, you know, 106 or whatever, and then in 107 the possibilities have been reduced. No matter what your intention is or your politics are, or your morality, you can’t just make it up. It has to come out of the context that you yourself have set up. So, then a work of fiction becomes a very specific meditation. It’s not a meditation on death; it’s a meditation on this one guy’s death under these conditions on this particular night. And then, then somehow, if you do it right, it has the feeling of being universal, which is another mystery for us to solve today.

***

George Saunders is the author of twelve books, including Lincoln in the Bardo, which won the 2017 Man Booker Prize for best work of fiction in English, and was a finalist for the Golden Man Booker, in which one Booker winner was selected to represent each decade, from the fifty years since the Prize’s inception. His stories have appeared regularly in The New Yorker since 1992. The short story collection Tenth of December was a finalist for the National Book Award and won the inaugural Folio Prize in 2013 (for the best work of fiction in English) and the Story Prize (best short story collection).