Helping Incarcerated Writers Find Their Voices at Parchman Prison

Since my first visit to Parchman to teach writing and literature in 2019, I have come to see prison writing as a unique body of literature that offers a commentary on the conditions that exist broadly in American society, specifically in the Mississippi Delta. The themes of the prison writing I have encountered flow seamlessly between poverty, abuse, education, and mental health, all issues that affect the lives of people in the Delta. As one prisoner wrote, “Poverty comes with an entourage” that includes “tragedy, crime, shame, pain and death. All of which I have gotten to know on a first-name basis.”

The men I have encountered over the years write about their past lives of poverty and deprivation in a way that is clear-eyed and lacking in sentimentality. Along with the bleak violence they are familiar with as part of their daily lives inside prison, they also intimately know the violence that exists outside the prison walls. Getting a group of eight men to write about their memories, both the good and the bad, helped me understand the problems of the Delta and forced me to confront the depth of the issues that live inside and outside prison walls.

Writers sometimes bloom in the darkest of circumstances, even inside the walls of a prison. Although the sun is shining brightly on the day I arrived for the first of my memoir writing classes, it seems the sky has darkened as soon as the prison gates close audibly behind our car. In the driver’s seat is Louis Bourgeois, who runs the Prison Writes Initiative. He tells me that he is no longer aware of the clanging of the gates, since he enters the prison at least twice every week. I remind him that I can never stop hearing the sound that makes me feel as if I am being locked away, even though I know that I will be leaving in two hours.

I learn that the men, regardless of race, had once lived a life of poverty. And crime was seen by each of them as a means of relieving the pain of poverty.

Parchman’s Unit 29 is a gray concrete building surrounded by a tall fence topped with razor wire that rests securely on miles of never-ending flatness and endless sky. Observation towers are placed strategically around the corners of the facility. While the prison grounds have no high fences, the prison units exist as separate fortresses, successors to the long wooden barracks that were once here. The journey from the gates of Parchman to Unit 29 takes the traveler past a mixture of modest brick and white clapboard houses, all of which once housed prison officials and employees. The most decrepit and weather-worn houses appear to be empty, although a few show outward signs that they are occupied.

Each time I arrive it feels as if I am traveling on a town’s main street rather than a road through a prison. That might have been intentional since at one time families of the employees in those houses lived on the grounds of the prison, often with prisoners working as house servants to the families. Generations of children grew up on these grounds. There was even once a grand residence for the prison superintendent that resembled a plantation house, but it is long gone.

Off in the distance, away from the units surrounded by gates and observation towers, a graveyard with a white arched gate sits in the midst of clear blue sky. From a distance it looks like it could be the gates of heaven. As you get closer you can see words just under the arch that say “Parchman Cemetery,” with a cross on each side. Beyond the gate are hundreds of white crosses, marking the graves of Parchman’s long-dead prisoners.

Although I could not find anyone who grew up on Parchman’s main street, I did meet someone who regularly played on the grounds of Parchman as a child. Stacey Sanford grew up in Tupelo but regularly visited her grandparents in Grenada, a town on the edge of the Delta. Her grandfather ran the machine shop at Parchman—one of her uncles worked there as well—and she spent a great deal of time at a place she just knew as “the shop.” “I didn’t even realize I was on the grounds of prison until I was in high school,” Sanford tells me one afternoon at a coffee shop in Oxford, where she now lives. She even still wears a ring an inmate who worked in the shop gave her made from stray bullet casings, as well as an assortment of other gifts. To Sanford, nothing about her regular trips to the grounds of Parchman seemed out of the ordinary.

Sanford’s time playing on the grounds of Parchman fell between the mid-1980s and the early 1990s, when she was between the ages of five and twelve, in the years after Parchman had been subject to a round of court-ordered reforms and before the years of mass incarceration. The men who worked with her grandfather were in vocational training—more than twenty inmates worked in the shop—which had become part of Parchman. Also, the prison had just become all male—before that change, there were roughly two hundred women imprisoned at Parchman—bringing the prison’s population at the time to just under four thousand. Her grandfather and uncle were the last of the almost exclusively white workforce that ran Parchman.

She has no memories of her grandfather’s truck undergoing a vehicle search before entering the prison grounds, as the car I ride in is routinely searched, or of seeing any of the prison facilities off in the distance. That surprises me, as I can see that prison buildings are visible from the machine shop, which I often drive past. Her memories of Parchman as a bucolic place rather than as a prison remind me that the children who grew up on the grounds of Parchman probably saw the place the same way.

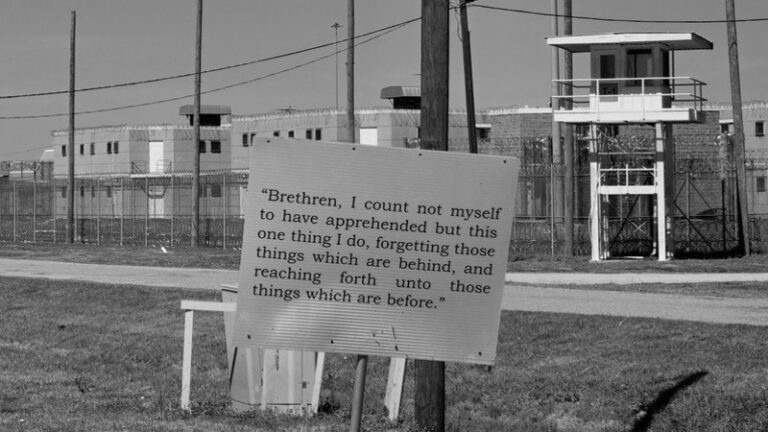

After a drive down what I think of as Parchman’s main street, you zigzag down weathered blacktop roads speckled with filled potholes—the prison roads are a grid that from the air appear as large rectangles—you arrive at Unit 29. Occasionally, men on horseback in prison stripes wander past, a reminder of the old trusty system that once existed here. “Parchman is a praying prison” the sign announces as soon as you get past the security gates. Every room includes a Bible verse prominently placed at eye level. Religion—particularly Christianity—plays an outsized role at Parchman.

Outside the observation tower for Unit 29 is a sign that reads, “Brethren, I could not myself to have apprehended, but this one thing I do, forgetting those things which are behind and reaching forth unto those things which are before.” The verse reappears across the grounds of Parchman. These are words from the apostle Paul, who is looking forward to the day when he will see the face of Christ rather than looking back at his failures. Paul is forgetting everything that was behind him, including the stoning of Saint Stephen the Martyr, who cried out as he was being stoned, “Lord do not hold this sin against them.” It seems an odd and fatalistic choice to place outside a facility that houses men who are in prison for life. Paul gets to do a victory lap; these men never will. Until they die inside this perpetual conflagration built from concrete and barbed wire, their sins will always be held against them.

The biblical references displayed on the grounds of the prison remind me that historian David Oshinsky once remarked that there were two reasons why Parchman exists: one was the desire for profit and the other was racial control. Now that Parchman is no longer a major source of state revenue and the staff is largely Black, religion has become the means of controlling the inmates. Today Parchman is all about sin, since once you enter its gates there is no chance for true redemption.

While there are various courses offered to inmates in Mississippi’s prisons, the only higher education degree available at Parchman is an associate’s or bachelor’s in theology from the New Orleans Baptist Seminary. The program was established to train inmates to be what are known as “inmate religious assistants,” so, unless a prisoner chooses to be a member of the clergy after release, the program is only useful inside prison walls, not outside them. It is also an educational option only for inmates with ten years remaining on their sentence, plus they must have no rule violations and a high school diploma. Half of incarcerated people in Mississippi lack a high school diploma or its equivalent, and many only read at a sixth-grade level.

The eight men who are part of my class all have high school diplomas. In preparation for the class, they have all read an essay by Henry Louis Gates Jr. called “Lifting the Veil,” in which Gates explores the ways he chose to explore the subtext of African American life fully in his memoir Colored People rather than keeping aspects of Black life “behind the veil.” I chose this essay to let them know that when they are writing about their past, they need only lift up the veil covering their past as much as they would like. Initially, the class is made up entirely of Black men, who quickly tell me that the idea of a veil placed over the lives of Black folks is one with which they are familiar.

A week later, two young white men join the class, and they also understand the idea of the veil. For the Black men, the veil is rooted in the racism that marginalized them from a broader society before they came to prison. For the white men, the experience of prison was the veil that now concealed them, rendering them strangers and exiles from the world outside.

Half of the men are from the Delta, and those who are from other parts of the state committed crimes in the Delta that landed them in Parchman. One was born near my father’s hometown in Choctaw County, Alabama, and ended up in the Delta, just as my father briefly did. Lacking the type of education my father had, his life took a different path. Even today, class and education serve as shields from the Delta’s violent culture. But none of these men had enough wealth or social standing to keep them out of prison. Their stories remind me of how violence is baked into the history and culture of the Delta and manifests itself in the prison population.

I think of Heraclitus’s axiom that “geography is destiny,” but I don’t proclaim those words in front this group. What I begin to understand is that geography does not have to be destiny. From each of them I learn that the men, regardless of race, had once lived a life of poverty. And crime was seen by each of them as a means of relieving the pain of poverty.

It doesn’t take long to recognize that they already see the connection between the places they are from and the circumstances that led to life imprisonment. Instead, I begin the class with a writing exercise that I often use: I ask them to find one small detail from their past, then write from the flood of memory for ten minutes and just see where the writing takes them. “Sometimes memories—often the best and the worst—burn inside us for a lifetime,” I tell them, quoting memoirist Mary Karr. “These memories ‘burn inside us for lifetimes, florid, unforgettable, demanding to be set down.’” It sets their writing in motion, their pencils audibly scratching their yellow pads.

After the ten minutes are up, I ask each of them to share what they have written. Most of them go deep into the memory vault of childhood, recalling fishing trips and family gatherings. One man opens his with, “Everything changed when we moved to Foley,” recalling how a childhood move disrupted his life in a way that he feels led to his imprisonment. Another writes, “I remember when I had a fan club,” thinking of his days as a high school football star and trying to understand how he moved from being idolized by his peers to being distanced from them in prison. Yet another remembers that the town where he is from is one of “bright lights and dark corners.” Then he writes that he fell into one of those dark corners, which in turn led him to Parchman.

I wanted to get them to blend the past before prison and the present conflicts inside the prison walls, and begin to recognize how the confluence of those parts of their existence affected their interior life.

At the end of our first two classes—by the second class, we have shrunk from eight to four men though later expand back to eight—I ask them to begin to craft a short memoir essay, one that we will workshop in a future class. Their ideas for their essays are sound and by the second class they lift the veil off their past even more, since they feel they can trust me. As I leave, I realize Dostoyevsky had it right: “Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart.” There is a great deal of intelligence among these men, along with much pain and suffering.

To keep them focused, each week I introduce a piece of writing, ask them to analyze it, and write a passage inspired by it. Reading Kiese Laymon’s essay “World’s Finest Chocolate” helped the men contemplate how they could capture their lives in a voice that felt as authentic as Laymon’s. Another week we read an essay by David Owen called “Scars,” in which the author contemplates the physical scars held on his body and the memories associated with those scars. This prompts one of the men—I’ll call him M.—to contemplate the psychological and physical scars he bears and how he intends to live with them. He writes:

My trials and tribulations have certainly been painful and have left deep psychological scars that have shaped who I am today. As have the years I’ve spent in prison, which have indeed left me with more physical scars than I came in with.

The best thing I can think to do with all these scars—psychological and physical—is to learn to live with them; embrace them; accept them for what they are: Proof that I am human.

What I learned from these discussions about writing and the craft of writing is that each man in the class had a desire to frame the life he led inside Parchman carefully on the page for all the world to see. Still, I kept pushing them to look beyond the vast, flat landscape they inhabited, one they could only view through a high steel fence capped by razor wire. It proved difficult. Their world inside Parchman was defined by regulation of contraband items, the work they were told to do, conflicts with other inmates, and the corruption and neglect of the prison administrators. I wanted to get them to blend the past before prison and the present conflicts inside the prison walls, and begin to recognize how the confluence of those parts of their existence affected their interior life, as well as the ways their life inside prison in some ways mirrored what existed in the world outside Parchman.

In seeking a piece of writing that would get them to begin to think about those ideas, I chose James Baldwin’s “Notes of a Native Son,” an essay that shifts between place and time. Baldwin takes the reader into the evolution of his feelings about his father, from hatred to mourning—the essay revolves around his father’s death—as well as the evolution of his views on racism in America, which move from innocence to a clear-eyed acknowledgment that racism must be confronted. “Notes of a Native Son” is an intimate essay that captures Baldwin’s emotional evolution toward an understanding of his complicated feelings.

What I did not know when I assigned this reading was that Baldwin had visited Unit 29 at Parchman in 1983. Baldwin had come to Mississippi to attend the annual Medgar Evers Homecoming celebration. He had been friends with Medgar Evers, who had served as the first field secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi until he was assassinated outside his home in 1963. Baldwin had visited the Evers’ family home to sign books for them, just months before Medgar Evers was killed. On this trip to Mississippi twenty years later, according to Mississippi state senator John Horhn—who accompanied Baldwin as a twenty-five-year-old employee of the Mississippi Arts Commission—Baldwin sought to honor Evers’s memory by connecting with prisoners at Parchman, first at death row and then at Unit 29.

The men all connected with “Notes of a Native Son,” and not just because Baldwin had visited Parchman. They all felt he understood their lives, which had been shaped by abuse, discrimination, poverty, and oppression just like Baldwin’s. One of the men, like Baldwin, had been a boy preacher. As a young Jehovah’s Witness in a suit and tie, he could sell more copies of The Watchtower than anyone—a boast he made repeatedly to me. By the age of six, this man I will refer to as R. was giving five-minute speeches before his entire congregation. He identified with Baldwin’s conversation with his father when he told him that he would rather write than preach. The two white men who joined the class the day Baldwin was assigned were also moved by the essay; the emotional events Baldwin recounts in his essay—his father’s death, his sister’s birth, and his own birthday, all falling on the same day—mirrored their own emotional lives and made racial discrimination feel real rather than theoretical.

__________________________________

Excerpted from When It’s Darkness on the Delta: How America’s Richest Soil Became Its Poorest Land by W. Ralph Eubanks. Copyright © 2026. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.