Honor Among Sportsmen by Richard Connell

“On week-days truffle hunting was confined to professionals; on Sunday, after church, all Montpont hunted truffles.”

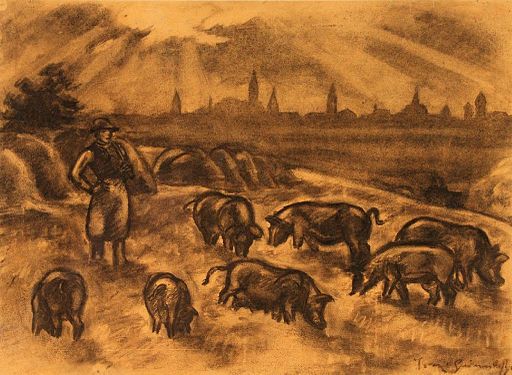

Each with his favorite hunting pig on a stout string, a band of the leading citizens of Montpont moved in dignified procession down the Rue Victor Hugo in the direction of the hunting preserve.

It was a mild, delicious Sunday, cool and tranquil as a pool in a woodland glade. To Perigord alone come such days. Peace was in the air, and the murmur of voices of men intent on a mission of moment. The men of Montpont were going forth to hunt truffles.

As Brillat-Savarin points out in his “Physiology of Taste”–“All France is inordinately truffliferous, and the province of Perigord particularly so.” On week-days the hunting of that succulent subterranean fungus was a business, indeed, a vast commercial enterprise, for were there not thousands of Perigord pies to be made, and uncounted tins of pâté de foie gras to be given the last exquisite touch by the addition of a bit of truffle?

But on Sunday it became a sport, the chief, the only sport of the citizens of Montpont. A preserve, rich in beech, oak and chestnut trees in whose shade the shy truffle thrives, had been set apart and here the truffle was never hunted for mercenary motives but for sport and sport alone. On week-days truffle hunting was confined to professionals; on Sunday, after church, all Montpont hunted truffles. Even the sub-prefect maintained a stable of notable pigs for the purpose. For the pig is as necessary to truffle-hunting as the beagle is to beagling.

A pig, by dint of patient training, can be taught to scent the buried truffle with his sensitive snout, and to point to its hiding place, as immobile as a cast-iron setter on a profiteer’s lawn, until its proud owner exhumes the prize. An experienced pointing pig, with a creditable record, brings an enormous price in the markets of Montpont.

At the head of the procession that kindly Sunday marched Monsieur Bonticu and Monsieur Pantan, with the decisive but leisurely tread of men of affairs. They spoke to each other with an elaborate, ceremonial politeness, for on this day, at least, they were rivals. On other days they were bosom friends. To-day was the last of the fall hunting season, and they were tied, with a score of some two hundred truffles each, for the championship of Montpont, an honor beside which winning the Derby is nothing and the Grand Prix de Rome a mere bauble in the eyes of all Perigord. To-day was to tell whether the laurels would rest on the round pink brow of Monsieur Bonticu or the oval olive brow of Monsieur Pantan.

Monsieur Bonticu was the leading undertaker of Montpont, and in his stately appearance he satisfied the traditions of his calling. He was a large man of forty or so, and in his special hunting suit of jade-hued cloth he looked, from a distance, to be an enormous green pepper. His face was vast and many chinned and his eyes had been set at the bottom of wells sunk deep in his pink face; it was said that even on a bright noon he could see the stars, as ordinary folk can by peering up from the bottom of a mine-shaft. They were small and cunning, his eyes, and a little diffident. In Montpont, he was popular. Even had his heart not been as large as it undoubtedly was, his prowess as a hunter of truffles and his complete devotion to that art–he insisted it was an art–would have endeared him to all right-thinking Montpontians. He was a bachelor, and said, more than once, as he sipped his old Anjou in the Café de l’Univers, “I marry? Bonticu marry? That is a cause of laughter, my friends. I have my little house, a good cook, and my Anastasie. What more could mortal ask? Certainly not an Eve in his paradise. I marry? I be dad to a collection of squealing, wiggling cabbages? I laugh at the idea.”

Anastasie was his pig, a prodigy at detecting truffles, and his most priceless treasure. He once said, at a truffle-hunters’ dinner, “I have but two passions, my comrades. The pursuit of the truffle and the flight from the female.”

Monsieur Pantan had applauded this sentiment heartily. He, too, was a bachelor. He combined, lucratively, the offices of town veterinarian and apothecary, and had written an authoritative book, “The Science of Truffle Hunting.” To him it was a science, the first of sciences. He was a fierce-looking little man, with bellicose eyes and bristling moustachio, and quick, nervous hands that always seemed to be rolling endless thousands of pills. He was given to fits of temper, but that is rather expected of a man in the south of France. His devotion to his pig, Clotilde, atoned, in the eyes of Montpont, for a slightly irascible nature.

The party, by now, had reached the hunting preserve, and with eager, serious faces, they lengthened the leashes on their pigs, and urged them to their task. By the laws of the chase, the choicest area had been left for Monsieur Bonticu and Monsieur Pantan, and excited galleries followed each of the two leading contestants. Bets were freely made.

* * * * *

In a scant nine minutes by the watch, Anastasie was seen to freeze and point. Monsieur Bonticu plunged to his plump knees, whipped out his trowel, dug like a badger, and in another minute brought to light a handsome truffle, the size of a small potato, blackish-gray as the best truffles are, and studded with warts. With a gesture of triumph, he exhibited it to the umpire, and popped it into his bag. He rewarded Anastasie with a bit of cheese, and urged her to new conquests. But a few seconds later, Monsieur Pantan gave a short hop, skip and jump, and all eyes were fastened on Clotilde, who had grown motionless, save for the tip of her snout which quivered gently. Monsieur Pantan dug feverishly and soon brandished aloft a well-developed truffle. So the battle waged.

At one time, by a series of successes, Monsieur Bonticu was three up on his rival, but Clotilde, by a bit of brilliant work beneath a chestnut tree, brought to light a nest of four truffles and sent the Pantan colors to the van.

The sun was setting; time was nearly up. The other hunters had long since stopped and were clustered about the two chief contestants, who, pale but collected, bent all their skill to the hunt. Practically every square inch of ground had been covered. But one propitious spot remained, the shadow of a giant oak, and, moved by a common impulse, the stout Bonticu and the slender Pantan simultaneously directed their pigs toward it. But a little minute of time now remained. The gallery held its breath. Then a great shout made the leaves shake and rustle. Like two perfectly synchronized machines, Anastasie and Clotilde had frozen and were pointing. They were pointing to the same spot.

Monsieur Pantan, more active than his rival, had darted to his knees, his trowel poised for action. But a large hand was laid on his shoulder, politely, and the silky voice of Monsieur Bonticu said, “If Monsieur will pardon me, may I have the honor of informing him that this is my find?”

Monsieur Pantan, trowel in mid-air, bowed as best a kneeling man can.

“I trust,” he said, coolly, “that Monsieur will not consider it an impertinence if I continue to dig up what my Clotilde has, beyond peradventure, discovered, and I hope Monsieur will not take it amiss if I suggest that he step out of the light as his shadow is not exactly that of a sapling.”

Monsieur Bonticu was trembling, but controlled.

“With profoundest respect,” he said from deep in his chest, “I beg to be allowed to inform Monsieur that he is, if I may say so, in error. I must ask Monsieur, as a sportsman, to step back and permit me to take what is justly mine.”

Monsieur Pantan’s face was terrible to see, but his voice was icily formal.

“I regret,” he said, “that I cannot admit Monsieur’s contention. In the name of sport, and his own honor, I call upon Monsieur to retire from his position.”

“That,” said Monsieur Bonticu, “I will never do.”

They both turned faces of appeal to the umpire. That official was bewildered.

“It is not in the rules, Messieurs,” he got out, confusedly. “In my forty years as an umpire, such a thing has not happened. It is a matter to be settled between you, personally.”

As he said the words, Monsieur Pantan commenced to dig furiously. Monsieur Bonticu dropped to his knees and also dug, like some great, green, panic-stricken beaver. Mounds of dirt flew up. At the same second they spied the truffle, a monster of its tribe. At the same second the plump fingers of Monsieur Bonticu and the thin fingers of Monsieur Pantan closed on it. Cries of dismay rose from the gallery.

“It is the largest of truffles,” called voices. “Don’t break it. Broken ones don’t count.” But it was too late. Monsieur Bonticu tugged violently; as violently tugged Monsieur Pantan. The truffle, indeed a giant of its species, burst asunder. The two men stood, each with his half, each glaring.

“I trust,” said Monsieur Bonticu, in his hollowest death-room voice, “that Monsieur is satisfied. I have my opinion of Monsieur as a sportsman, a gentleman and a Frenchman.”

“For my part,” returned Monsieur Pantan, with rising passion, “it is impossible for me to consider Monsieur as any of the three.”

“What’s that you say?” cried Monsieur Bonticu, his big face suddenly flamingly red.

“Monsieur, in addition to the defects in his sense of honor is not also deficient in his sense of hearing,” returned the smoldering Pantan.

“Monsieur is insulting.”

“That is his hope.”

Monsieur Bonticu was aflame with a great, seething wrath, but he had sufficient control of his sense of insult to jerk at the leash of Anastasie and say, in a tone all Montpont could hear:

“Come, Anastasie. I once did Monsieur Pantan the honor of considering him your equal. I must revise my estimate. He is not your sort of pig at all.”

Monsieur Pantan’s eyes were blazing dangerously, but he retained a slipping grip on his emotions long enough to say:

“Come, Clotilde. Do not demean yourself by breathing the same air as Monsieur and Madame Bonticu.”

The eyes of Monsieur Bonticu, ordinarily so peaceful, now shot forth sparks. Turning a livid face to his antagonist, he cried aloud:

“Monsieur Pantan, in my opinion you are a puff-ball!”

This was too much. For to call a truffle-hunter a puff-ball is to call him a thing unspeakably vile. In the eyes of a true lover of truffles a puff-ball is a noisome, obscene thing; it is a false truffle. In truffledom it is a fighting word. With a scream of rage Monsieur Pantan advanced on the bulky Bonticu.

“By the thumbs of St. Front,” he cried, “you shall pay for that, Monsieur Aristide Gontran Louis Bonticu. Here and now, before all Montpont, before all Perigord, before all France, I challenge you to a duel to the death.”

Words rattled and jostled in his throat, so great was his anger. Monsieur Bonticu stood motionless; his full-moon face had gone white; the half of truffle slipped from his fingers. For he knew, as they all knew, that the dueling code of Perigord is inexorable. It is seldom nowadays that the Perigordians, even in their hottest moments, say the fighting word, for once a challenge has passed, retirement is impossible, and a duel is a most serious matter. By rigid rule, the challenger and challenged must meet at daybreak in mortal combat. At twenty paces they must each discharge two horse-pistols; then they must close on each other with sabers; should these fail to settle the issue, each man is provided with a poniard for the most intimate stages of the combat. Such duels are seldom bloodless. Monsieur Bonticu’s lips formed some syllables. They were:

“You are aware of the consequences of your words, Monsieur Pantan?”

“Perfectly.”

“You do not wish to withdraw them?” Monsieur Bonticu despite himself injected a hopeful note into his query.

“I withdraw? Never in this life. On the contrary, not only do I not withdraw, I reiterate,” bridled Monsieur Pantan.

In a requiescat in pace voice, Monsieur Bonticu said:

“So be it. You have sealed your own doom, Monsieur. I shall prepare to attend you first in the capacity of an opponent, and shortly thereafter in my professional capacity.”

Monsieur Pantan sneered openly.

“Monsieur the undertaker had better consider in his remaining hours whether it is feasible to embalm himself or have a stranger do it.”

With this thunderbolt of defiance, the little man turned on his heel, and stumped from the field.

Monsieur Bonticu followed at last. But he walked as one whose knees have turned to meringue glace. He went slowly to his little shop and sat down among the coffins. For the first time in his life their presence made him uneasy. A big new one had just come from the factory. For a long time he gazed at it; then he surveyed his own full-blown physique with a measuring eye. He shuddered. The light fell on the silver plate on the lid, and his eyes seemed to see engraved there:

MONSIEUR ARISTIDE GONTRAN LOUIS BONTICU

Died in the forty-first year of his life on the field of honor.

“He was without peer as a hunter of truffles.”

MAY HE REST IN PEACE.

With almost a smile, he reflected that this inscription would make Monsieur Pantan very angry; yes, he would insist on it. He looked down at his fat fists and sighed profoundly, and shook his big head. They had never pulled a trigger or gripped a sword-hilt; the knife, the peaceful table knife, the fork, and the leash of Anastasie–those had occupied them. Anastasie! A globular tear rose slowly from the wells in which his eyes were set, and unchecked, wandered gently down the folds of his face. Who would care for Anastasie? With another sigh that seemed to start in the caverns of his soul, he reached out and took a dusty book from a case, and bent over it. It contained the time-honored dueling code of ancient Perigord. Suddenly, as he read, his eyes brightened, and he ceased to sigh. He snapped the book shut, took from a peg his best hat, dusted it with his elbow, and stepped out into the starry Perigord night.

* * * * *

At high noon, three days later, as duly decreed by the dueling code, Monsieur Pantan, in full evening dress, appeared at the shop of Monsieur Bonticu, accompanied by two solemn-visaged seconds, to make final arrangements for the affair of honor. They found Monsieur Bonticu sitting comfortably among his coffins. He greeted them with a serene smile. Monsieur Pantan frowned portentously.

“We have come,” announced the chief second, Monsieur Duffon, the town butcher, “as the representatives of this grossly insulted gentleman to demand satisfaction. The weapons and conditions are, of course, fixed by the code. It remains only to set the date. Would Friday at dawn in the truffle preserve be entirely convenient for Monsieur?”

Monsieur Bonticu’s shrug contained more regret than a hundred words could convey.

“Alas, it will be impossible, Messieurs,” he said, with a deep bow.

“Impossible?”

“But yes. I assure Messieurs that nothing would give me more exquisite pleasure than to grant this gentleman”–he stressed this word–“the satisfaction that his honor”–he also stressed this word–“appears to demand. However, it is impossible.”

The seconds and Monsieur Pantan looked at Monsieur Bonticu and at each other.

“But this is monstrous,” exclaimed the chief second. “Is it that Monsieur refuses to fight?”

Monsieur Bonticu’s slowly shaken head indicated most poignant regret.

“But no, Messieurs,” he said. “I do not refuse. Is it not a question of honor? Am I not a sportsman? But, alas, I am forbidden to fight.”

“Forbidden.”

“Alas, yes.”

“But why?”

“Because,” said Monsieur Bonticu, “I am a married man.”

The eyes of the three men widened; they appeared stunned by surprise. Monsieur Pantan spoke first.

“You married?” he demanded.

“But certainly.”

“When?”

“Only yesterday.”

“To whom? I demand proof.”

“To Madame Aubison of Barbaste.”

“The widow of Sergeant Aubison?”

“The same.”

“I do not believe it,” declared Monsieur Pantan.

Monsieur Bonticu smiled, raised his voice and called.

“Angelique! Angelique, my dove. Will you come here a little moment?”

“What? And leave the lentil soup to burn?” came an undoubtedly feminine voice from the depths of the house.

“Yes, my treasure.”

“What a pest you are, Aristide,” said the voice, and its owner, an ample woman of perhaps thirty, appeared in the doorway. Monsieur Bonticu waved a fat hand toward her.

“My wife, Messieurs,” he said.

She bowed stiffly. The three men bowed. They said nothing. They gaped at her. She spoke to her husband.

“Is it that you take me for a Punch and Judy show, Aristide?”

“Ah, never, my rosebud,” cried Monsieur Bonticu, with a placating smile. “You see, my own, these gentlemen wished