How Benjamin Franklin’s Cold Feet Led to a Revolutionary American Invention

Maybe some odd drift in the smoke above the chimney gave it away. But otherwise, a historic laboratory in a private home at 131 Market Street, Philadelphia, was invisible from the outside. The building is long gone, no plaque commemorates what was discovered there, but this was where Benjamin Franklin investigated his first atmosphere.

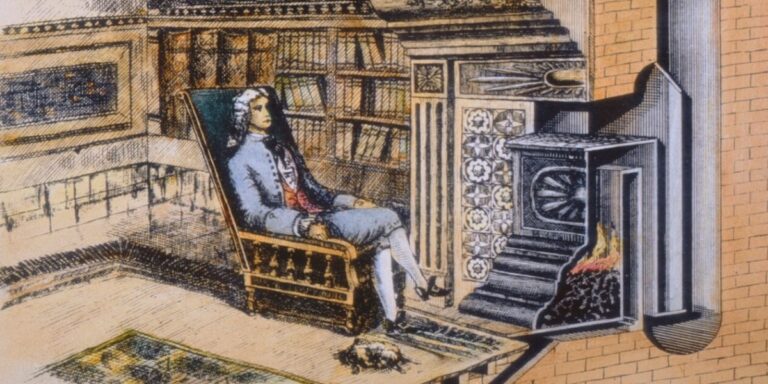

Later portrayed as a godlike master of nature—thunder, lightning, ocean currents—he began it all with experiments in heating his family’s sitting room, starting in the late 1730s, trying to minimize both fuel use and emission of smoke, right as the weather got colder (yet again) in the 1740s. The result was Franklin’s first invention, the Pennsylvanian fireplace, a metal insert for a hearth with a chimney, starting with the one in his parlor on Market Street.

Franklin’s fireplace may have conserved wood, but it used a lot of paper. Printed accounts of the worsening winters and of the newly invented fireplace made paper media part of ongoing adaptation to climate change, no less than the stoves. Franklin did so much reporting about cold weather that his work as a printer was, intentionally or not, the foundation for his new heating system. He established himself as a weather expert, a reliable source of information about how bad the cold might be, and yet how it wasn’t as bad as elsewhere, all of which made him a reassuring guide to some of Pennsylvania’s coldest intervals, for which he proposed a scientific solution.

This particular winter, icy midwife to the Franklin stove, raises questions about how people experience and respond to climate change.

His project was conservationist, an energy regime to slow the loss of woodlands that already troubled Britain and was beginning to plague Philadelphia and its environs. The connections to greater atmospheric phenomena would come later—Pennsylvania’s social and material atmosphere was the immediate context for Franklin’s initial work. The parlor on Market Street was the microcosm, the colony the macrocosm; functionally interdependent, neither could have existed without the other, with everyday heating the measure of Pennsylvania’s opportunities, inequities, comforts—starting with the discomforts of yet more bad winters.

*

In The Pennsylvania Gazette for March 5, 1741, Franklin related how “Accounts from all Parts of the Country are fill’d with Complaints of the Severity of the Winter, no one remembering the like. The Cattle are daily dying for want of Fodder; many Deer are found dead in the Woods, and some come tamely to the Plantations and feed on Hay with other Creatures.” By spring, the weather was better but the damage more apparent. On April 9, the paper reported that some colonists had resorted to eating the dead deer. And, Franklin said, Natives warned that wild animals might be “scarce for many Years.” This Indigenous testimony, from past experience, identified an unexpected hazard of clearing away natural resources. Poor Richard’s Almanack for 1742 further noted, in January, that, with the freezing of waterways, “Foot, Horse, and Waggons, now cross Rivers, dry, / And Ships unmov’d, the boistrous Winds defy.” Everything was strange, “by Snow disguis’d.” Bad news for everyone unless the trend reversed. Which it did not.

The winter of late 1740 to early 1741, with its deadly white landscape, was a turning point. It stood out, not as the worst winter of the eighteenth century, but as the memorable first of a sequence, all occurring within colonists’ living memory and documented in multiple accounts. A rival Philadelphia printer, Franklin’s former employer Andrew Bradford, gave an extended account of the winter in his American Magazine, North America’s first magazine, launched on February 13, 1741—three days before Franklin’s own attempt, The General Magazine. Bradford’s magazine lasted only three issues, and Franklin’s, six, but while they appeared, they gave the city’s snowbound readers very welcome reading material.

The American Magazine offered a weather diary for “this last hard winter”—snow, ice, frozen roads, more snow, more ice, roads thawing into icy mud—from October 27, 1740, to April 19, 1741. The account concludes that it would be “a great Apple Year, but few Peaches,” foreign trees marking the colony’s natural fortunes. Scooped by Bradford, Franklin frostily ignored the ongoing weather in his 1741 magazine, but commemorated it later, in his almanac for 1749. In the calendar notes for March, he reminded readers that, “on the 13th of this month, 1741, the river Delaware became navigable again, having been fast froze up to that day, from the 19th of December in the preceding year.” So far, he said, 1740–1741 had offered “the longest and hardest winter remembred here.”

That winter was also the first time Philadelphia’s officials considered subsidizing firewood for poor white people who, in this wealth- and credit-starved era, struggled to scrape together money for anything. Franklin indicated his support with some foreign news: as in Pennsylvania, “the Winter has been excessively severe in England, beyond any thing in the Memory of Man, by which the Poor have suffer’d extreamly, notwithstanding vast Sums of Money, and Quantities of Coals, Bread, &c. distributed among them in Charity.” One way or another, in harsh winters, someone had to pay for heat.

This particular winter, icy midwife to the Franklin stove, raises questions about how people experience and respond to climate change. Historians have studied the winter of 1740–1741 in Europe, where its shortening of the growing season caused famine in several places. In Ireland, as much as one-fifth of the population died, a toll possibly higher than during the better-known Great Famine of 1845–1852; the disaster triggered notable out-migration (including to Pennsylvania). And yet climate scientists cannot identify proxy data for a significant temperature variation.

This indicates weather’s complex relation to other material circumstances (in Europe, the cold interacted with drought and disease), and that human accounts of weather events may document not just natural conditions but cultural expectations. The new demand for greater indoor comfort may have made colonists into more sensitive weather instruments—and into pickier consumers with a greater sense of entitlement. Toughing out a bad winter was less acceptable. By the 1740s, people expected to be able to make artificial atmospheres indoors, as Franklin did.

In case a little schadenfreude cheered up anyone in Pennsylvania, things were even worse elsewhere in North America. In his Poor Richard of 1748, under January, Franklin would note that “we complain sometimes of hard Winters in this Country; but our Winters will appear as Summers” compared to those in “Hudson’s Bay.” Franklin supplied several detailed pages about this place where, in winter, everything existed in various states of ice. “And now, my tender Reader, thou that shudderest when the Wind blows a little at N-West, and criest ‘Tis extrrrrrream cohohold!’…what dost thou think of removing to that delightful Country?”

New England remained Franklin’s main point of comparison for any harsh weather. On February 11, 1752, The Pennsylvania Gazette reported that, on January 6 in Boston, it had “been observed by Gentlemen who keep Thermometers, that for several Days last Week, it was colder by 7 or 8 Degrees, than it has been for many Years past.” Mail from England was delayed. Meanwhile, Boston Harbor froze so hard that, by sled or on foot, an “abundance of People pass daily from the Town to Castle William, and the Islands.” Only with much heroic chopping of ice from the harbor’s channel could ships depart.

Even after Franklin retired from his printing business in 1748, his printer contacts and his newspaper (edited by his business partner) would monitor the weather. The winter of 1764–1765 set more records, as The Pennsylvania Gazette reported multiple times: three feet of snow between December 25, 1764, and January 14, 1765; a two-day blizzard in March that deposited another two and a half feet of snow; and the freezing over of the Delaware River, which closed Philadelphia’s port and delayed all traffic, including postal service.

In January, Franklin’s protégé James Parker, public printer in New York and eventual postmaster in New Haven, sent word to Franklin (at that point in London) of the dire conditions. Snow had begun to fall hard on Christmas Day and didn’t stop until it lay three to six feet deep; the Delaware and Brunswick Rivers froze and were closed to navigation. “It is thought by most,” Parker wrote on January 14, “that from the 25th Decem. to this Day, the Weather has exceeded the hard Winter of 1740.”

The “new world” turned out not to be a wondrously refilling cornucopia. Its resources were finite, too.

The solution, winter after winter, was to try to keep warm at home, a running joke (at best) on the human condition in the northern colonies. A Massachusetts almanac for 1777 would admit, for example, that fireplaces could smoke up a house, making people cough and dredging their furnishings and clothing in soot. “How to hinder a House from smoaking?” The obvious answer was to “KEEP no fire in it; if a fire is already made, throw a sufficient quantity of water on to quench it, and the smoak will soon depart.” (This is indeed foolproof.) Another Boston almanac for the same year joked about finding anything to burn in the first place.

Almanacs often supplied recipes and this one obliged with a “Recipe to keep one’s self warm a whole Winter with a single billet of Wood,” meaning one large, reusable chunk. Just carry this remarkable source of heat upstairs, at top speed, throw it out the window into the yard below, then race downstairs to fetch it up again. “This renew as often as Occasion shall require.” Again, there’s an undeniable logic to it.

Logical, except the solution simply swaps one fuel for another, food in the belly for wood on the hearth, giving a person the strength to douse a smoky fire or thunder up and down the stairs. Food wasn’t necessarily cheaper than firewood. And, therefore, all jokes aside, the real problem with fireplaces was securing wood to burn in them in the first place, rather than being cold while listening to the wind moan in the chimney.

The cost of keeping warm fell unevenly, with the richest suffering the least—a transhistorical constant. For James Logan, who built Pennsylvania’s grandest house, Stenton (completed in 1730), money was no object: smack in the front hall he had a huge open fireplace, the most ostentatious and wasteful heating choice. This despite a complex ventilation system in Stenton’s dining room, indicating Logan’s familiarity with Nicolas Gauger, whose book on heat and fuel efficiency he had in his grand and expensive library. He knew about minimizing fuel use; he didn’t need to bother with it, except to show off his book learning about it.

But for an ordinary colonial family in the early eighteenth century, fuel represented 9 percent of a typical household budget—in a typical year. (In comparison: the average energy burden for non-low-income US households in 2024 was 2 percent, though for low-income households it was 6 percent.) In the Little Ice Age, unusual cold persistently raised the price of keeping warm. For poorer people, that meant decisions that affected health if not life. Things were even worse for enslaved people, dependent on provisions of clothing and food that were barely adequate in any winter, and, if they lived outside a town, often tasked with getting their own firewood. All this was exacerbated by rising fuel costs. By the 1730s, seaport towns in British America had cut down their nearest woods. They had to import fuel from farther away, transport costs adding to the expense. In Philadelphia, a cord of wood ran from 8 to 10 shillings between 1700 and 1735, then from 10 to 13 shillings between 1736 and 1750.

Within a scant two generations, English colonists along the coast of North America had replicated conditions that, in Europe, dated back to the Middle Ages. The “new world” turned out not to be a wondrously refilling cornucopia. Its resources were finite, too. Unless some burnable treasure lay buried within it? In his Winter Meditations, Cotton Mather had noted that God’s creation included “Numberless Fossils in the Bowels of the Globe, which probably contains above Ten Thousand Millions of Cubic German Leagues.” Probably. If true, then huge amounts of mineral wealth, including coal, remained to be discovered, probably. Only, in the meantime, it was not just probable but obvious that North America’s trees were vanishing.

__________________________________

From The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution by Joyce E. Chaplin. Copyright © 2025. Available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan, Inc.