How Many Licks? On Tootsie Pops, Desire and the Science of Delayed Gratification

An über-candy, the psychic template for American lollipops. A serious classic, unstoppable, good fresh and good old and good even after having melted in the car, when you have to pull the wrapper off as best you can, then suck until you can remove the last bits of paper, squinting as sunshine strobes through the trees as your mother drives you home from a doctor’s appointment.

This pop was a two-step pleasure. First, the hard candy outside—in cherry or raspberry or slightly disappointing orange, or the rarer grape or chocolate—then the chewy chocolate inside. Was the hard carapace just a prelude or an event unto itself? They were named, after all, for what was inside. The candy’s slogan presented this dilemma as an urgent modern mystery: “How many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop?” Not a catchy sentence, but still a fun game.

In the cartoon ads, a bland little boy took his query to a succession of animals, most memorably an owl, who would try to answer the question—“Wah-unn, two-hooo!, tha-reee”—and then fail, crunching into the candy sphere with his beak as desire overtook him. He wore glasses, his big blue eyeballs filling the round frames, and he was crowned with a mortarboard. He was a professor, a physicist of candy, and even he couldn’t resist messing up the experiment. How many licks? Well, a serious voice would intone, “The world may never know.”

Watching this ad, I and many other thousands of children resolved to find out, to patiently melt down that outside shell in a manner calculable and recorded. Surely we could crack the mysteries that confounded adults and cartoon animals. It seemed a simple task, to lick without biting, to enjoy one pleasure while waiting for another.

Was the sugar more delicious for the children who waited…or for the children who plunged forward and ate the first marshmallow immediately?

It was impossible. I always bit, impatient for the Tootsie Roll nugget inside. That was the part that really made your mouth water, even if it was mostly in response to the sudden shift in texture, the center so yielding and immediately rewarding. The hard-candy outside would shatter into tiny pieces, which melted instantly like snowflakes on the tongue. It was a pleasurable failure, a queer sensation. There were choices to be made, the ego and the id in a delicate dance, but there was wisdom to giving in to desire. As the challenge had been presented, so, too, had the joy of defeat—Mr. Owl was played, after all, by Paul Winchell, also the original voice of Tigger, that purveyor of delightful chaos.

I still crunch into a Tootsie Pop before its hard-candy shell has entirely faded away. This alters my usual rhythm of candy eating, which is characterized by savoring—patient licks, gentle melting, doling out individual pieces to make the experience last as long as possible. What I cannot do is delay the start: if there’s candy in the house, it’s monumentally difficult for me not to eat it. It magnetizes my attention. In the presence of candy, there is no neutral state. There is eating or distraction.

I have always wondered how I would fare (as a child and, if we’re being honest, today) in the infamous Stanford marshmallow experiment, in which researchers imprisoned kids in a bare room with a single marshmallow and told them that if they waited fifteen minutes to eat it, they would earn a second one. Setting aside the question of how this torture got IRB approval, I want to state that marshmallows are one of the least exciting possible candies with which to run this experiment. (Are they even candies? Really more of an ingredient.)

But I get it: they are uniform in shape, plain white, pretty purely just sugar, and resistant to vagaries of personal taste and allergy. Unless you’re vegan. Unless you have issues with corn syrup. (Helen Betya Rubinstein, in her excellent essay “On Not Eating the Marshmallow,” points out that this study could no longer be run at the preschool where it originated, given parental food anxieties.) They tested the kids in the 1970s, then tracked their life success, as measured by all the boring, typical American markers—test performance, thinness, coolness under pressure.

The initial results were published in Science in 1989, when I was eight, and that paper and all later follow-ups asserted the value of delayed gratification: Kids who were able to wait for that second marshmallow had higher SAT scores. They had lower BMIs, were more popular. They were less likely to get divorced. We don’t know if they were kinder, more creative, more likely to feel their lives had purpose.

It’s true that delaying gratification has benefits: if you focus enough to do your homework before going outside to play, day after day, the system will reward you. Or so we thought. Researchers at NYU and UC Irvine recently ran the marshmallow test again, this time with a larger, more diverse group of kids. When the results were adjusted for household income and other factors of privilege, the ability to wait for the second treat had a limited effect on “success.” Poor kids who exerted self-control did no better in life than those who didn’t, and the same went for the rich kids. It was—surprise—the groups’ relative poverty or affluence that made the real difference.

So Mr. Owl was right to chomp, and I was foolish to think myself wiser than a professorial raptor. The recent study even found that affluent kids were better able to wait for that second marshmallow, proving once more that abundance replicates itself. Not only did their backgrounds set them up for high test scores, but their comfort in the world got them more candy in laboratory settings. This aligns with other research that shows that those who struggle financially are more likely to avail themselves of short-term rewards, even those they can’t technically afford, and that poor parents are more likely to give in when their kids ask for sugar.

What the marshmallow experiment, in both its iterations, failed to measure was the children’s enjoyment of the marshmallows. This seems an egregious oversight, for what are all those personal and professional accomplishments worth if our path to attaining them is dull? Numerous studies suggest that effort and anticipation increase happiness and enjoyment. (My favorite is “Waiting for Merlot: Anticipatory Consumption of Experiential and Material Purchases.”) But still, I wonder: was the sugar more delicious for the children who waited—made sweeter not just by the neurological processes of anticipation and reward but by being evidence of that sweetest thing, a fulfilled promise—or for the children who plunged forward and ate the first marshmallow immediately, sharpening their enjoyment with a transgressive edge?

There’s a danger in delaying our gratifications indefinitely. Much has been made of the paradoxical decisions that those who bear the crushing weight of scarcity sometimes make—stories about poor parents buying their kids PlayStations when they can’t afford organic vegetables, or lottery tickets as a “poverty tax,” always get traction. We’re eager to punish those who would seek excess or joy before attending to basic needs, while ignoring how difficult or impossible it might be to ever cover those bills. How long should people wait to live? How big should people be allowed to dream?

Less attention has been paid to those who, raised in poverty, obsessively conserve money and resources, who, after having pulled themselves out of precarity, still feel unsafe, feel intense guilt about small indulgences, who, when they receive that second marshmallow, still sit staring, eating neither of them, who are given a Tootsie Pop at the bank and then carry it in their pocket, saving it for someday, a someday they never allow themselves, never recognize, until it’s sticky and covered in lint.

Struggle is unbearable without hope, and hope, for kids, takes the form of imagination, of magic.

The marshmallow kids who could imagine the two-marshmallow future so vividly that it became more real than the fragrant, glowing single marshmallow before them were the ones who could hold out. They had hope that the researcher would return—they had learned that adults kept promises. Their parents had rarely picked them up late due to car trouble, had rarely failed to buy them a promised gift because the money ran out. The kids who ate the first marshmallow, the thinking goes, had been let down too many times to believe that the second one would appear.

But maybe those kids felt hope, too. Maybe they indulged because they thought there might be more lab days in the future; bought the PlayStation because, sure, they couldn’t afford it now, but things were bound to improve any minute; bit into the Tootsie Pop because there would be countless other chances to run the experiment and beat Mr. Owl.

Struggle is unbearable without hope, and hope, for kids, takes the form of imagination, of magic. Hidden on certain rare Tootsie Pop wrappers, we learned, was a spell: a boy in a headdress drawing an arrow across a bow, pointed at a star. (Tootsie Roll Industries, I think you can retire the magical Native American trope now, as several Indigenous groups have asked you to.) You could save these special wrappers and redeem them for… toys? Free candy? A million dollars? It was never clear. But supposedly, if you handed the wrapper to a benevolent grocery store clerk you would receive a prize, and then all daily magic would be reinforced.

I’ve since learned that this character is no rarer than any other image on the Tootsie Pop toile wrapper, and of course the whole thing was an urban legend. But I saved them, never tried to redeem them. I kept them in a little box with other treasures, signs that I was lucky, that Mom and I were, that maybe someday our weekly lottery tickets would erase all our worries and we would have everything we wanted, whenever we wanted it. In the meantime, Mom let me eat as much candy as I pleased.

__________________________________

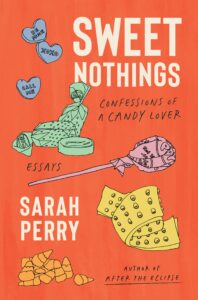

Excerpted from the book Sweet Nothings: Confessions of a Candy Lover by Sarah Perry. Copyright © 2025 by Sarah Perry. Illustrations © 2025 by Forsyth Harmon. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.