How Shirley Jackson Exposed the Darker, Uncanny Side of Everyday Life

In August 1950, a story by Shirley Jackson created a sensation. No, not “The Lottery,” although that one was met with an uproar immediately upon its publication two years earlier in The New Yorker—it sparked the most letters the magazine had ever received about a work of fiction, with some readers going so far as to cancel their subscriptions in protest. This was a sensation of a different kind. Jackson and her husband, literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, were featured speakers at a writing conference recently started by John Farrar, her editor at the publishing firm then known as Farrar, Straus. Jackson almost never taught writing in an academic setting, but she loved the intimate atmosphere of a conference. “I read a story and answer questions…it is three days of being treated like somebody important,” she wrote in a letter to her parents, with whom she corresponded regularly throughout her life.

For her reading, Jackson chose a new story, “only just finished and never published.” At the end, she looked up and saw that Farrar was crying, along with everyone else in the room. (Everyone, that is, “except Stanley, who had heard the story before.”) As usual, Farrar invited questions. “A guy in the front row got up and said flatly that it was not possible to ask any questions or to discuss this story in any way,” suggesting that “everyone tiptoe out peacefully,” Jackson reported in her letter. “All the rest of the time we were there people kept coming up to me tearfully and pressing my hand and going away again.”

Men aren’t simply devils—the dark heart of Jackson’s fiction beats with a more complex rhythm than that. Women are capable of losing their grasp on their own.

The story was “A Visit,” which I was delighted to find included in this volume. Though Jackson was known to improve on reality in her letters, I wouldn’t be surprised if it really did reduce a room to tears. It’s one of my personal favorites among Jackson’s stories‚ as well as one of her own favorites. In my biography of Jackson, I didn’t devote much analysis to it, as it is “so mysterious and uncanny that to paraphrase it ruins the effect.” This seemed like the perfect opportunity to examine it in greater detail. But when I sat down to read it again, I found myself as hopelessly and wordlessly under its spell as the conference attendees who were the first to hear it seventy-five years ago. Sometimes Jackson’s stories just have that effect.

*

Shirley Jackson’s career was too brief—she died in 1965 at the age of forty-eight—but prolific and wide-ranging: she completed six novels as well as dozens of short stories and two comic memoirs about her household, which included four children, an ever-evolving assortment of pets, and her absentminded-professor husband. In Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, I argued back against critics who had pigeonholed her as a horror writer, pointing to the diversity of her output as well as to her understated use of the supernatural. The majority of Jackson’s stories are grounded in realistic characters and situations: the isolated woman in a society where marriage was essential for social acceptance, the town busybody who meddles disruptively in the lives of others, the tensions between husbands and wives.

All those themes are present in this volume. But—as the work gathered here demonstrates—even Jackson’s most domestic stories often need only the slightest push to take a turn into the uncanny. In “The Beautiful Stranger,” another of my favorites, a young wife picks up her husband from the train station and discovers him subtly, unmistakably changed. The title character of “The Missing Girl” disappears from summer camp: has she run away or been abducted, or has something weirder and more sinister taken place?

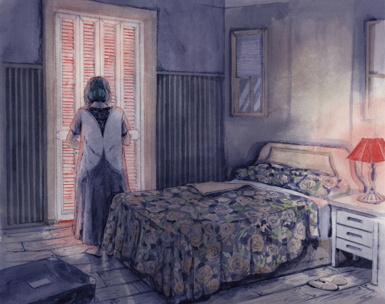

Sometimes the reader is privy to the mystery, as in “All She Said Was Yes,” in which a determinedly literal woman takes in a neighbor’s daughter after her parents are killed in an accident and is unable to hear what the girl tries to tell her. (An early title for this story was “Cassandra.”) But more often we’re not. In “The Daemon Lover”—which is, next to “The Lottery,” perhaps the best-known story in this collection of less frequently seen work—a New York City woman, no longer young (“You’re thirty-four years old after all, she told herself cruelly in the bathroom mirror”), waits for her fiancé to pick her up for their City Hall wedding. She dresses carefully, makes up her face, changes the bedsheets and towels, drinks a cup of coffee. As the morning turns into afternoon and he doesn’t appear, her mental state fractures. Eventually she takes to the streets, asking everyone he might have passed—the newsdealer, the florist, a policeman—if they have seen a man in a blue suit. When she finally finds his apartment, it’s abandoned.

The only clue that this might be something other than a broken engagement is the man’s name: James Harris. Here we see Jackson’s trademark technique of putting a modern spin on an old fable. “The Lottery” takes the symbol of the scapegoat, which appears in the mythology of many pre-modern cultures, and places it in a setting that looks very much like a New England village in the 1940s. “The Daemon Lover” updates a British legend about a man sometimes calling himself James Harris who presents himself as a sailor, promising to swoop a married woman off to a beautiful land far away from the drudgery of her life. Once aboard his ship, she discovers he is the devil in disguise, taking her to the snowy mountain of Hell. In a sequence of stories that appeared in her 1949 collection, The Lottery—its original subtitle was “The Adventures of James Harris”—this figure walks the streets of New York, bringing women to the point of disintegration.

Judging from the stories gathered here, the woman in “The Daemon Lover” may have gotten off easy. In “The Honeymoon of Mrs. Smith” and “The Good Wife,” marriage spells disaster for a woman; in “What a Thought,” the wife is the instigator of violence. But men aren’t simply devils—the dark heart of Jackson’s fiction beats with a more complex rhythm than that. Women are capable of losing their grasp on their own.

In “Louisa, Please Come Home,” one of Jackson’s most deeply affecting stories, a girl on the cusp of womanhood runs away from home and disappears into a new life in a new city, where she finds a room in a boarding house and a job in a stationery store. Jackson’s agent, who judged it “a powerful and brilliant horror story,” quibbled with her decision to leave the character’s motive unexplained, but it’s clear that Louisa doesn’t need a reason to run away. She wants simply to disappear, to begin a new life untethered from the old, even if that means giving up everything. But it can be easier to leave home than to find your way back again. Louisa’s reinvention turns out to be so effective that when she ultimately does return home, her family fails to recognize her. Louisa sees that it is hopeless to argue. “I hope your daughter comes back someday,” she tells her own parents.

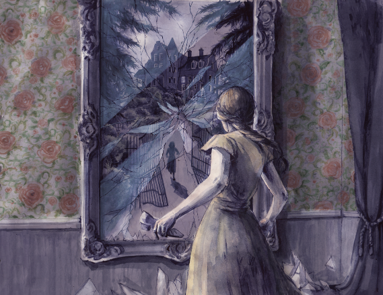

Jackson’s writing process could be difficult and protracted: multiple versions, sometimes very different, exist for some of the stories here. In the initial version of “Louisa, Please Come Home,” the main character is a grifter who tries to impersonate a runaway girl, fooling her parents but not her sister. Similarly, readers who know The Haunting of Hill House will notice that at least two of the stories here initiate themes that Jackson would bring to fruition in that sublime novel. “The Story We Used to Tell” likely dates to Jackson’s college days or shortly thereafter: its structure, in which a first-person narrator has adventures with a female friend identified by the initial ‘Y,’ corresponds to others Jackson wrote very early in her career. (‘Y’ was her nickname for a friend from the University of Rochester, which she attended for two years before transferring to Syracuse University.) Here, the narrator visits Y, a young widow, in the old house that has been her family home for generations, where they discover that a painting of the house opens up a portal to another world.

Even if characters are not physically alone, they are existentially isolated: entrapped inside their home, stuck outside of it unable to get in, ostracized from their community.

“A Visit,” sometimes subtitled “The Lovely House,” offers another fantasy of escape that ends in entrapment. A young woman named Margaret visits a friend who lives in a storybook mansion surrounded by a river and hills, with stone sculptures and tapestry-bedecked walls and a room with a mosaic depicting a girl’s face with the text, “Here was Margaret, who died for love.” Soon a man arrives who charms and seduces Margaret, taking her on picnics and telling her the history of the house. Driven by curiosity about the mysterious tower room, Margaret enters it and finds the castle’s resident madwoman, a great-aunt hidden away: her name, too, is Margaret. “All is lost,” ghostly echoes whisper in a house whose repeating patterns—in life as well as in architecture—ultimately turn into an unending series of reflections. Jackson’s dialogue is so subtle and the story unspooled so carefully that its final twist lands no less violently than the ending of “The Lottery.” Like all the best reversals, it leads the reader back to question everything that came before, including the nature of reality itself.

*

In The Haunting of Hill House, four people gather to investigate paranormal activity in a legendary haunted house. Early in the novel, they try to define fear, and their answers, while phrased differently, are essentially the same. “I think we are only afraid of ourselves,” suggests Dr. Montague, the organizer of the investigation. “Of seeing ourselves clearly and without disguise,” suggests another. “Of knowing what we really want,” says the third. Only Eleanor, the novel’s protagonist, who will ultimately break apart under the pressure of the house, responds in the first-person singular. “I am always afraid of being alone,” she says.

How might Shirley Jackson have answered this question? If the stories in this volume are any indication, Eleanor might be speaking for her. The terrible pain of loneliness is a constant. “Being lonely is worse than anything in the world,” muses the protagonist of “The Beautiful Stranger,” who is so desperately alone within her own marriage that she welcomes the stranger who has apparently replaced her husband. Even if characters are not physically alone, they are existentially isolated: entrapped inside their home, stuck outside of it unable to get in, ostracized from their community. It’s not always other people who are the villains—these figures may be victims of their own blinkered mentality. (“I feel sort of like we belong here,” Mrs. Allison says innocently of the town where she and her husband vacation in “The Summer People,” ignoring all the signs that they definitely do not.) But many of their journeys end with the realization of their profound aloneness.

A reader unfamiliar with Shirley Jackson’s work will find many of its famous pleasures here—foremost “The Lottery,” which still retains its power to shock. But her other gifts are also amply on display, especially her sense of humor. (“It’s a lovely house,” Ethel thinks in “Home,” shortly before ghosts hijack her car.) Perhaps more than anything else, these stories demonstrate Jackson’s extraordinary ability to create and sustain a mood. Whether they’re read aloud in a room full of admirers or at home alone on a dark night, they are among the most beguiling works of literature I know.

__________________________________

From The Lottery and Other Dark Tales by Shirley Jackson, illustrated by Angie Hoffmeister. Copyright © 2025. Available from The Folio Society.