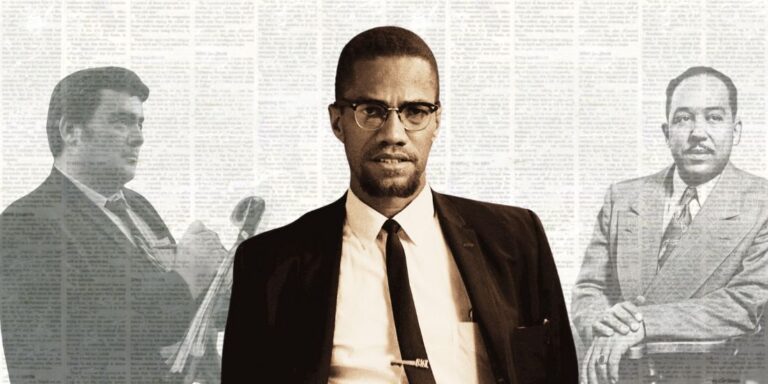

How Two of America’s Biggest Columnists Reacted to the Assassination of Malcolm X

Shortly after 3pm on Sunday, February 21, 1965, a team of assassins gunned down Malcolm X at the Audubon Ballroom in uptown Manhattan. In the aftermath, rivers of ink spilled across New York City’s many newspapers, with two leading literary voices of the 20th century weighing in.

Jimmy Breslin had gained a national reputation in 1963 with his first book Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? a sparkling account of the New York Mets’ pathetic first season. After the assassination of JFK that November, he penned one of his most famous columns.

Titled “It’s an Honor,” Breslin’s short entry provided an unorthodox view of the president’s funeral. Explaining why he was proud to perform his task, African-American undertaker Clifton Pollard assured Breslin that JFK “was a good man.”

As recently explained by Library of America (LoA) editor James Gibbon, Breslin’s choice of perspective spawned the “Gravedigger Theory of Journalism,” spurring reporters to seek out views of major events through unexpected sources. Breslin’s columns during the mid-1960s appeared in the New York Herald Tribune, a paper that provided a home for the era’s new journalism.

The LoA’s 2024 collection of Breslin’s writings includes his story about the X slaying. It does not mention how the Herald Tribune’s editors presented the piece, however. Between the paper’s logo and its large headline about X’s murder read a familiar quote:

“Chickens coming home to roost never did make me sad; they’ve always made me glad!”

–Malcolm X exalting at the assassination of President Kennedy

*

Malcolm denied that he had been “exalting” at JFK’s murder, calling it a media distortion. But the immediate outrage at his comment was so great that Elijah Muhammad suspended X from speaking on behalf of the Nation of Islam. It’s not clear whether Breslin encouraged his editors to run the quote as an epigraph. But it’s not hard to see how the controversial statement influenced the Irish-American liberal writer’s jaundiced view of Malcolm X.

In reality, Malcolm was a 39-year-old renowned world leader, and he had not engaged in underworld activity since leaving prison over a dozen years before his murder.

Breslin began his recap by stating that the Audubon Ballroom audience of over 300 people was “the best crowd that Malcolm has had in a long time.” The pugnacious journalist’s tone turned even crankier when he followed the shooting victim to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.

“The white hands that Malcolm X had preached so much hatred about clawed at his blood-soaked clothes and touched his body,” Breslin wrote regarding the medical staff. The next three sentences also refer to “white hands.” The efforts to save X, Breslin continued, were ultimately “meaningless” because the “bullets had done the job.”

The reporter’s callousness towards a man shot to death in front of his wife and children led him to a jarring set of conclusions. “Malcolm X was a leader without a following of any numbers,” insisted Breslin. “He was a 30-year-old ex-pimp, narcotics pusher and ex-convict who preached violence against the white man but had not raised a hand in violence in years and his reputation came from white newspapermen who built him into an illusion.”

In reality, Malcolm was a 39-year-old renowned world leader, and he had not engaged in underworld activity since leaving prison over a dozen years before his murder. Both FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and CIA Deputy Director Richard Helms closely monitored X’s activities in February 1965, suggesting that Malcolm’s power was much more than an “illusion.”

Alas, Breslin was not finished writing off X’s importance. The columnist declared that Malcolm was a “shallow, uneducated guy” who succeeded by “frightening people” and making white people “nervous.” That Malcolm scared the establishment, white and Black, is not in doubt. But Breslin’s absurd dismissal of X’s rhetorical brilliance is a stain on the former’s legacy.

*

Although only 64, Langston Hughes was in the twilight of his multi-faceted career. Amid World War II, his popular column in the Chicago Defender began recording events of the day as seen from the Harlem barstool of Jess B. Simple, a fictional character who conveyed the views of working-class African Americans.

Hughes appears to suggest that Malcolm and his fellow Black Muslims existed in a world apart from average Black Harlemites.

Five days after Malcolm’s murder, Simple showed up in Hughes’ column in the then-liberal New York Post. At the outset of an entry called “Scars,” Hughes’ character offered two somewhat cryptic observations about X.

Simple tells the narrator (Hughes) that the two should discuss “important” issues, such as “Why Malcolm X changed his name to Malik El-Shabazz before he died. Or how come, if you are a Black Muslim, a man can change his name any time he wants to.”

The column then moves in an unrelated direction, with Simple holding forth about his Cousin Minnie. Simple, it seems, is not particularly torn up by X’s assassination. Hughes appears to suggest that Malcolm and his fellow Black Muslims existed in a world apart from average Black Harlemites.

During the 1930s-40s, Hughes’ circles included Communists. As Black Power began to emerge in the mid-1960s, the writer neither embraced nor denounced the next generation of radicals. Two years after X’s death, Hughes succumbed to cancer.

Sixty years after Malcolm X’s murder, we still do not know many essential details of the event. Yet Malcolm’s status as a global icon has continued to grow, in ways that neither Jimmy Breslin nor Langston Hughes could have envisioned.