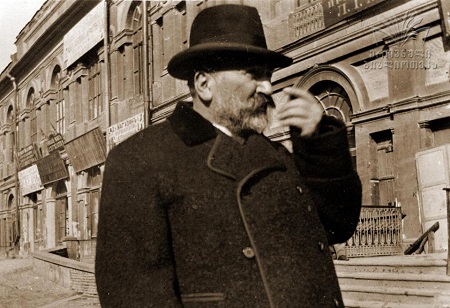

Ilia Chavchavadze – Autobiography

I was born on October 27 (o. s.) 1837 in the village of Kwareli (*1), in the district of Telavi, in the province of Tiflis in the region comprising also the district of Signakh, called Cakheti. My father (Grigol) was a man of some education, he served as an officer in the Nizhegorod dragoons and had a good knowledge of the Russian language.

My mother was remarkable for her intimate acquaintance with the Georgian literature of her day, she knew almost by heart nearly all the poetry and all the ancient tales and stories then to be found in manuscript and print. She loved to read in the evenings to us her children stories and tales, and after reading would tell them over again in her own words and in the next evening whoever of us repeated best what he had heard the night before was rewarded by her praise, which we greatly prized.

I began my studies by learning my native Georgian language with the deacon of the parish at the age of eight. This deacon was distinguished for his knowledge of Georgian; he was famous as a good reader of the holy books and was especially gifted with the fascination of a splendid narrator. His stories, suited to the childish comprehension in form and substance, dealt with separate episodes of the religious, but more particularly the civic history of our country and consisted of narrations of various heroic exploits in defence of the faith and fatherland. Many of these tales left an impression on my memory and served me many years afterwards as subjects for a poem, “Dimitri the Self-sacrificing” and a short Christmas story. Some passages in my Story of a Beggar exhibitmarks of this influence. I learned my lessons at the deacon’s with the peasant children of my native village, of whom there were only five or six as far as I recollect. We all lived at home and only came from morning till midday. So far as I remember we only spent an hour a day learning to read and write, and all the rest of the time till noon was spent in games under the supervision and guidance of the deacon, and especially, in listening to his alluring stories.

In my eleventh year my father took me to Tiflis and sent me to Raevski and Hacke’s boarding-school, then the best of all the private schools in Tiflis. I was fifteen when from this Boarding-school I proceeded to the fourth class in the Tiflis Grammar School, still remaining as a boarder in the former house, which was now managed by Hacke alone.

Hacke was a German, a thoroughly educated man in every way. He had been engaged from Germany by Neidhart, who was at that time commander of the detached Caucasian Corps, for the education of his children, and after the termination of his engagement with Neidhart he opened a boarding school with Raevski who had been previously engaged in educational work in Tiflis. Hacke, though, strict and exacting, was so paternally attentive to his pupils, so painstaking and anxious for their moral and intellectual development, that he devoted to then nearly all, his time after school hours, conversing with them, diverting them with music, giving them improvised concerts on the pianoforte, which he played to perfection.

Having gone through the eighth class of the Grammar School and not passed the final examination in 1857 I entered the University of St. Petersburg as a student of the then-existing cameral section of the Faculty of Jurisprudence, and in 1861, when I was in my fourth year of residence, I left the University in consequence of the so-called “Student Affair” (political) of that period.

In 1863 I founded the journal “Sakarthvelos Moambe” (Georgia’s Messenger) which only lasted a year. In the same year 1863 I married Princess Olga Guramishvili.

At the beginning of 1864, when the reform for the liberation of the peasants in the district of the Viceroy of the Caucasus was planned, I was sent to act in the province of Kutais as official private Secretary to the Governor General of Kutais, in order to determine the nature of the mutual relations between landlords and peasants arising from the servile dependence of the latter on the former.

In November of the same year, 1864, the liberation of the peasants from servile dependence had already been effected in the province of Tiflis and I was appointed Arbitrator of the Peace in the Dushet district of the province of Tiflis and in that office I remained down to the year 1868, when upon the introduction of the new judicial organization in the Caucasus I was given the office of Justice of the Peace in the same district of Dushet. In this latter office I remained till 1874.1 think it may not be superfluous to remark here that the nobility of the province of Tiflis, having received on the abolition of servile dependence an imperial grant for the personal liberation of the peasants, a part of this grant was allotted for the establishment of a credit institution, capable of meeting the need for a regularly organized system of credit, and especially with the proviso that its profits should be exclusively devoted to the education and instruction of the children of the nobility of the province of Tiflis. After much hesitation in this search for a suitable form of credit institution, the nobility in 1874, on my advice, decided upon the establishment of a Land Bank and entrusted a special Committee, of which I was elected a member, to draw up the statute .The statute formulated by the committee in accordance with the models supplied by the Government for their guidance and passed in the same year 1874 by the nobility differs from all other statutes of land banks in this noteworthy peculiarity, that all the profits of the Bank, excluding the obligatory deductions on account of sundry capital sums, are applied to the satisfaction of the common needs not only of the landowning nobility but of the agricultural population of the province of Tiflis. Thus, the Land Bank of the Tiflis Nobility is probably the only agrarian credit institution in all the Russian Empire whose statute entirely eliminates the personal interest of gain for the sake of attaining aims of a social character.

In the same year 1874 the nobility commissioned me to proceed to St. Petersburg and procure the confirmation of the statute they had passed and in consequence of this I retired from the Government Service.

The statute with the above mentioned peculiarity was confirmed by Government in 1875, From that year the Bank began its operations and from a founder’s capital of. only 240 000 roubles ( £ 24 000) it has now (1902) reached such a position that it yields a yearly profit of over 360 000 roubles (£ 36 000), in spite of the fact that all the founder’s capital subscribed by noblemen, has already been paid back to the nobility. From the day of the opening of the Bank down to the present time I have been President of the Board of the Bank. This office is elective and tenable for a term of three years.(*2)

In 1877 I founded a weekly Georgian newspaper “Iveria”, which afterwards became a monthly magazine, and from 1885 a daily political and literary paper. In 1902 I handed over the paper to another person who now edits it.

Of my works in translations by various hands there are in Russian only some short verses and one poem “The Hermit” in Mr. Tkhorzewsky’s version. The Russian translations of my verses are partly comprised in a separate collection published in Tiflis, and partly appeared in “Russkaya Mysl”, “Zhivopisnoe Obozrenie” “Viestnik Evropy” and I forget where else.

My poem “The Hermit” was translated into English (verse) by Miss Marjory Wardrop and also into French (prose).German translations of some of my short pieces in verse were put into the collection first published at Leipzig in 1886 by Arthur Leist under the title “Georgesche Dichter” and re-issued at Dresden in 1900. Critical notices duly appeared in the local Russian newspapers “Kavkaz” and “Novoe Obozrenie”, and as well as I can recollect, in the metropolitan journals “Russkaya Mysl” and “Zhivopisnoe Obozrenie”, also in another Moscow periodical the name of which, to my regret I have forgotten.

Abroad, criticisms were inserted in some German periodicals including, the “Litterarisches Echo” and in the “Academy” and the Italian review “Nuova Antologia” No. VI of 1900 Notices with reference to my public and literary work are found in “Le Caucase Illustre”, Tiflis 1902.

In 1877 I was elected Vice President of the Imperial Agricultural Society and held that office for some time, and I was elected President of the Georgian Dramatic Society from 1881 to 1884. I am President of the Society for the Propagation of Literacy among the Georgians since 1886, I was member of the committe of the Society of the Nobility of the province of Tiflis for the Assistance of Necessitous Scholars. I have taken part, whether by invitation or election, in almost all committees charged with the …

My literary labours began in 1857 with the printing in the magazine “Tziscari” (The Dawn) of short verses, then my works appeared in the newspaper “Droeba” (Time), “Crebuli” (the Garner), in “Sakartvelos Moambe” (Georgian Messenger) and “Iveria” both of which I founded) and partly in the now-existing magazine “Moambe”.

In addition to shorter verses, I have written some poems: “Episodes from the Life of a Brigand”, “The Vision”, “Dimitri the Self Sacrificing’; “The Hermit” and a dramatic sketch “Mother and Son”. Of my tales I may mention: 1) “Katzia Adamiani?!” (Is that a man?!) printed in 1863 in “Georgia’s Messenger” and afterwards published in Petersburg by the Society of Georgian students, 2) “The Story of a Beggar” printed in the same journal and in the same year, which also appeared as a separate work; 3) Scenes from the early days “of the emancipation of the peasants”, printed in 1865 in “Crebuli” and afterwards published separately. 4) “Letters of a Traveller” printed in 1864, also in “Crebuli”, 5) “The Widow of the House of Otar” 1888; 6) “A Strange story” printed in “Moambe”, 7) “A Christmas Story” 8) “The Four Gibbets” in “Iveria”.

I translated Pushkin’s “Propheth” Lermontov’s “Prophet”, “Hadji Abrek” and “Mary” and Turgeniev’s “Verses in Prose” and some verses of Heine and Goethe. I also translated, in collaboration with Prince Ivane Machabeli, Shakespeare’s “King Lear”. I took part in the restoration of the original text of the famous Georgian poem “The Man in the Panther’s Skin”, also in editing: a) the poems of Prince Alexandre Chavchavadze, b) the poems of Vakhtang Orbeliani”, for which I wrote a preface, c) The ancient Georgian story of “Vis and Ramin”.

In addition to these literary works I have written many short articles of political journalistic, critical and polemical character, also articles on educational questions. Among the most bulky of the journalistic publications may be mentioned “The Khizan Question”, “Life and Law”, “Concerning Brigandage in Transcaucasia”. Of the critical and polemical articles may be mentioned two which were printed as feuilletons in “Iveria”: “And You Call that History?!” (on Rustaveli) and “Armenian Savants and Outcrying Stones” the last of these recently appeared in a ussian translation and caused much ado in the local Armenian press.

Of the edition of my complete collected works undertaken by the local Georgian Publishing Society, so far 4 volumes have appeared out of the proposed 10 or 12 volumes. The volumes already published include verses, tales, stories and dramatic sketches.

(*1) The translator’s style and spelling of Georgian and Russian names are preserved intact.

(*2) By 1907 a private Grammar school was supported from the profits of the Bank, with a boarding – house for children of the poorest among the nobility and a day school for children of all classes; also an agricultural school for children of all classes.

Ilia Chavchavadze

Works

Translated by Marjory and Oliver Wardrops

Ganatleba Publishers

Tbilisi 1987

The book features some works of Ilia Chavchavadze translated into English by brother and sister Oliver and Marjory Wardrop. The translations have not lost their literary value to the present day. The publication is intended as a gift to the Georgian reader in connection with the 150th anniversary celebrations of the birth of the outstanding Georgian writer and public figure. Text prepared for publication, with a preface and notes by Ia Popkhadze. Edited by Dr. Guram Sharadze.

PREFACE

The special interest shown by, Marjory and Oliver Wardrop for Georgian spiritual culture is well known. By translating a number of literary works they gave the versatile English reader an idea of Georgian literature with its centuries — old tradition.

The spiritual affinity of the Wardrops with Ilia Chavchavadze, a great son of Georgia, was not accidental. Their genuine sympathy was confirmed by the translation of the eminent Georgian writer’s literary works, which they did with affection and reverence.

Hitherto the reading public was aware only of Marjory Wardrop’s English translation of Ilia’s “The Hermit” (London 1895). In recent years (1981, 1984) Prof. Guram Sharadze has discovered some other translations in the Wardrop collection of the Bodleian Library, at Oxford pointing to a broader scale of the translational activity of the Wardrops. Apart from “The Hermit”, the following renderings of Ilia’s prose are presented for the first time here: “Notes of a Journey from Vladikavkaz to Tiflis”, “Is that a Man?!” (fragments), “The Sportsman’s story” (several chapters),” Autobiography”.

Chavchavadze’s poetic heritage is represented by these titles: “Spring”, “The Sleeping Maid”, “Elegy”, “Ah!… She — to whom My Dear Desires…” an extract from the poem “The Vision” (“O our Aragva”), “Bazalethi’s Lake” (abridged).

The texts of these translations were prepared for publication according to the autographs preserved at Oxford, the xeroxed copies of which were brought from England by Prof. Sharadze and kindly transferred to the present writer for publication. The text of “The Hermit” is published according to the London edition of 1895, the latter now being a rare book.

Today the greatest merit of these translations would seem to lie in the inner warmth and affection with which they were done, which will always be remembered by the grateful Georgian people.

IA POPKHADZESearch …