Inside James Baldwin’s Fraught Relationship With His Stepfather

Baldwin describes how his father’s illness led to him “hating and fearing every living soul including his children who had betrayed him, too, by reaching towards the world which had despised him.” As my father’s illness took over his brain, he would tell my mother that he was going to kill himself. Slamming the door shut, he wandered out of their flat and into the heart of the market town where they lived. Sometimes he would return, usually with cigarettes, within ten minutes, but there was a period when he took to sitting with the local drinkers and homeless men and women. He wanted to sleep on the streets, he explained to my mother, and he wanted to help these people who had nothing, something which had always concerned both my parents.

“You see that man,” he would say when I was young, pointing carefully to a figure we would often see walking the banks of the River Severn. “He’s a gentleman of the road; the richest man in Shropshire. Everything belongs to him.”

*

James Baldwin was in fact born James Jones. His mother, Berdis, was born in either 1902 or on Christmas Day the following year, on Deal Island off the coast of Maryland, also known as Devil’s Island—a tiny inhospitable isle of around three square miles that is susceptible to flooding. Little is known about Berdis, who first appears on a census in 1940, where her birthplace is listed as Maryland, along with her age (thirty-eight). Softly spoken and reputed to have a brilliant mind and love of poetry, she was so petite that the writer Maya Angelou recalled she would have to stoop down just to kiss her on her forehead. At some point Berdis moved north in search of work, first to Philadelphia and then to New York City, where she gave birth in 1924, out of wedlock, to her first son, whom she called Jimmy.

If Baldwin found peace with his stepfather after his death, then his early writing was an exorcism of sorts.

Baldwin was born as the New Negro Movement—or Harlem Renaissance as it was also known—was gathering momentum, an unprecedented flowering of Black American artistic and cultural production that lasted until the mid- to late 1930s. It was a period, as the writer Langston Hughes recalled, in which the “Negro was in vogue,” during which time Black American writers, artists and musicians, among them Zora Neale Hurston, Alain Locke, Jacob Lawrence and Louis Armstrong, displayed a new vision for African American culture and identity that would pave the way for the Civil Rights Movement.

Baldwin’s arrival during the Harlem Renaissance notwithstanding, he rarely alluded to the cultural achievements of his forebears. Baldwin would often mention that he was moments away from being born in the South, a place that Berdis and so many of her generation fled. In the early twentieth century, after cotton crops were decimated by the boll weevil, an innocuous-looking insect with a long snout that devours cotton, and after biblical floods—as depicted in the “Back-Water Blues,” sung by Bessie Smith, one of Baldwin’s favorite singers—African Americans looked for work in the northern cities of Detroit, Philadelphia, Chicago and New York.

Pockets of northern cities, including Harlem, were populated, as Baldwin would have experienced, by people who had, like Berdis, been born in the South. The North was something of a promised land, where work could be found and where the threat of racial terror, including lynchings, was less pronounced. Berdis was part of the First Great Migration, when around 1.5 million African Americans refused to stay in the South, a land a whisper away from slavery where they endured Jim Crow segregation and relentless poverty.

Baldwin wrote about the American South in one of his earliest essays, “Journey to Atlanta” (1948), which recounts a trip his brother David took as part of a gospel quartet in the mid-1940s, which, expanded and retold, was recast in his last novel, Just Above My Head (1979), in which one member of the singing troupe is murdered in the South, described elsewhere by Baldwin as the “blood-stained land.” In addition to essays such as “Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South” (1959), Dixie rears up in menacing ways in several of his other works, including his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), in which an unnamed Black soldier, a veteran of the Great War, is found beaten and castrated in the Deep South. “The South had always frightened me,” Baldwin states in his essay “A Fly in Buttermilk” (1958), and he writes elsewhere that “I felt as though I had wandered into hell” on his first trip there.

Little is known about Baldwin’s biological father. Of his first few years of family life, he recalled that “I was the only child in the house—or houses—for a while, a halcyon period which memory has quite repudiated.” When Baldwin was two or three years old, his mother met and married David Baldwin, a laborer and preacher from Louisiana who was one generation away from slavery. Baldwin recalls tugging at his mother’s skirts to get her attention, because “I was so terrified of the man we called my father, who did not arrive on my scene, really, until I was more than two years old.” As Baldwin remembers, his stepfather moved in, along with his mother, Barbara, who had been born into slavery, and who was “so old that she never moved from her bed.”

Baldwin’s recollections of his new father are couched in a language of hate, resentment and fear. David’s first appearance in Baldwin’s non-fiction takes place in “Autobiographical Notes,” the opening essay of Notes of a Native Son. His mother, Baldwin recalls, was “delighted” with his early literary experiments, including plays and songs; his father “wasn’t,” Baldwin explains, for “he wanted me to be a preacher.” Baldwin’s brief description of his parents’ responses to his early creative experiments sets the tone for his subsequent writing. Berdis, who “was given to the exasperating and mysterious habit of having babies,” is rarely mentioned. She is there in fleeting memories of his impoverished childhood, where she “fried corned beef, she boiled it, she baked it, she put potatoes in it, she put rice in it, she disguised it in corn bread, she boiled it in soup (!), she wrapped it in cloth…” Years later, when Baldwin was imprisoned for the theft of a bedsheet in Paris, he experienced a recurring nightmare involving his mother’s fried chicken, in which “At the moment I was about to eat it came the rapping at the door.”

Mostly, however, Berdis is present in Baldwin’s writing as a buffer between the aspiring writer and his strict and loveless stepfather. His mother “paid an immense price for standing between us and our father,” Baldwin recalls, adding that David knew how to make Berdis suffer. And while his mother, who outlived her son, held the growing family together, it was David, an embittered evangelical, who looms in Baldwin’s earliest writings. As one of Baldwin’s biographers puts it: “To the people of his house the father’s prophecy took the form of an arbitrary and puritanical discipline and a depressing air of bitter frustration which did nothing to alleviate the pain of poverty and oppression.” Beatings accompanied this “bitter frustration” and his stepfather repeatedly told Baldwin that he was ugly.

By the time he had reached his thirties, Baldwin explained that he understood his father, who “was very religious, very rigid,” much better. “He wanted Negroes to do, in effect, what he imagined White people did,” Baldwin recalls, “that is to have—to own the houses, to own U.S. Steel.” But this frustration, Baldwin states, “in effect, killed him. Because there was something in him which could not bend.” Looking back over his childhood, Baldwin concludes that “My father frightened me so badly, I had to fight him so hard, that nobody has ever frightened me since.”

But if Baldwin found peace with his stepfather after his death, then his early writing was an exorcism of sorts, a way of seizing back control from the man who tyrannized his childhood. Go Tell It on the Mountain took him a decade to write. He lugged the tattered manuscript around during his early years working in New York and New Jersey, and then over to Paris when he flew to France in 1948, completing his debut work of fiction in the small village of Loèche-les-Bains, also known as Leukerbad, which is nestled high in the mountains in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. And while Go Tell It on the Mountain—the title borrowed from a well-known African American gospel—travelled across the Atlantic, surviving cheap Left Bank hotels in Paris and the journey to Switzerland, its subject was very close to home for the aspiring writer.

The story, which draws heavily on Baldwin’s childhood, takes place on a single day, the fourteenth birthday of John Grimes, who, like Baldwin, was expected to become a preacher, like his stepfather. But while the narrative present of the story is March 1935, the story moves back in space and time to the South and to before Baldwin was born. It was a novel, he explained, that “I had to write if I was ever going to write anything else. I had to deal with what hurt me most. I had to deal, above all, with my father. He was my model; I learned a lot from him.”

Baldwin’s explanation of how he had to write Go Tell It on the Mountain is couched in a language of torn emotions. He had to deal with David Baldwin’s cruelty—but he acknowledges that his stepfather, the source of his unhappiness, was also his model. In several essays Baldwin recalls how his stepfather controlled his children’s lives. Jazz and blues music were forbidden by the zealous Baldwin Snr., as they were linked in his mind to a deviation from the path of the Lord. The cinema was viewed with great suspicion and so were white people. David Baldwin warned James “that my white friends in high school were not really my friends and that I would see, when I was older, how white people would do anything to keep a Negro down.”

Baldwin ignored his father’s injunction to avoid befriending white people. At DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he was one of the few Black students in a predominantly Jewish cohort, Baldwin’s classmates included Emile Capouya, who later became literary editor of the Nation, and Sol Stein, a writer and publisher, as well as the renowned photographer Richard Avedon, with whom Baldwin edited the school’s magazine, Magpie. But while he shared artistic pursuits with his non-Black classmates, his experience was distinct. He read voraciously, including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestselling novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, “over and over again,” explaining that “in fact, I read just about everything I could get my hands on—except the Bible, probably because it was the only book I was encouraged to read.” But in contrast to his white friends, even searching out books could be menacing: “Why don’t you niggers stay uptown where you belong?” a police officer mutters to the thirteen-year-old Baldwin on his way to the library.

The simplicity with which the tensions between Baldwin and his stepfather are resolved belies the years of struggle to reach that point.

In “Autobiographical Notes,” Baldwin pegs the King James Bible as one of his influences: his childhood was pulled in the direction of the Word and words. Between the ages of fourteen and seventeen, Baldwin became, as he later put it, a “holly roller” preacher in a Pentecostal church. For his father, Baldwin’s passion for reading and writing was a distraction from the way of the Lord, a tension that culminated in a terse conversation between the two of them when Baldwin was seventeen years old:

My father asked me abruptly, “You’d rather write than preach, wouldn’t you?”

I was astonished at his question—because it was a real question. I answered, “Yes.”

That was all we said. It was awful to remember that that was all we had ever said.

The simplicity with which the tensions between Baldwin and his stepfather are resolved belies the years of struggle to reach that point. “When he was dead I realized that I had hardly ever spoken to him,” Baldwin recalled. “When he had been dead a long time I began to wish I had.” But it is the final two sentences of the above exchange that hit me most, a recollection that Baldwin wrote in the wake of his father’s death: “that was all we had ever said.” My own father, a ghostly presence of a man who was always so present in every room he occupied, is alive, but his memories of me have died. We can sound out words to one another, but we no longer converse beyond stop–start phrases. Each encounter with my father carries for me the burden of recognition when I believe, just for a moment, that he knows who I am, before these fleeting moments wither in the stale air of the care home.

I catch myself talking about my father in the past tense. How he used to delight in reading poetry and chatting to strangers; how he used to love pubs. Sometimes my father is silent, and I hang on every utterance as though he is an oracle emerging from a vow of silence. I lean in closely and notice that his teeth are stained and I wonder who brushes them for him. Is he compliant, like my toddler on a good day, or does he protest and push his carer aside? When he was eight years old, he lost his front two teeth playing cricket when his bat top-edged the ball from an older bowler. My grandmother once told me that he was still smiling through the blood and broken teeth. Now I feed him crisps, one at a time, which he seems to enjoy. When I pause to reach for a plastic cup of water, he continues the motions of eating, delicately placing invisible morsels into his now silent mouth.

I stare into my father’s eyes and hope I can see a flicker of something that has survived the cruel efficiency of Alzheimer’s. He is staring through me, through the walls of the home, and into a space I hope never to go. I am reminded of William S. Burroughs’ description of a junky whose “face wasn’t blank or expressionless. It simply wasn’t there.” But my wife sees sadness in his eyes and I think she’s right. My own eyes fill but I try not to cry, fearing this might upset my father. At one point he murmurs the name of my maternal aunt, who took her own life several years ago.

Many years before, my father told one of my sisters that she should run him over if he suffered from dementia. He speaks a few words in French, takes my hand in his atrophied fingers and kisses the back of it with the delicacy of a courtesan. As we walk with him through the corridors, where Doris and her friends are swaying to an ABBA song, we are hit by the stench of piss and death, but also small moments of joy among the residents, as well as terror. “The next time…” my father says, and I lean in, hungry to take home a nugget of my father’s old self. But words never come, and the incomplete sentence is cast away in the corridors of the home as I ponder the banality of Alzheimer’s. I hug his bony frame and walk out without looking back.

__________________________________

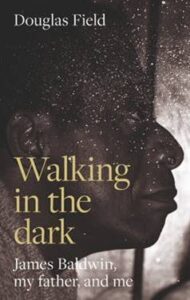

From Walking in the Dark: James Baldwin, My Father, and Me by Douglas Field. Copyright © 2024. Published by Manchester University Press and available from all good bookstores and online.