Joe Jackson on the Spanish-American War and Trump’s Imperial Ambitions

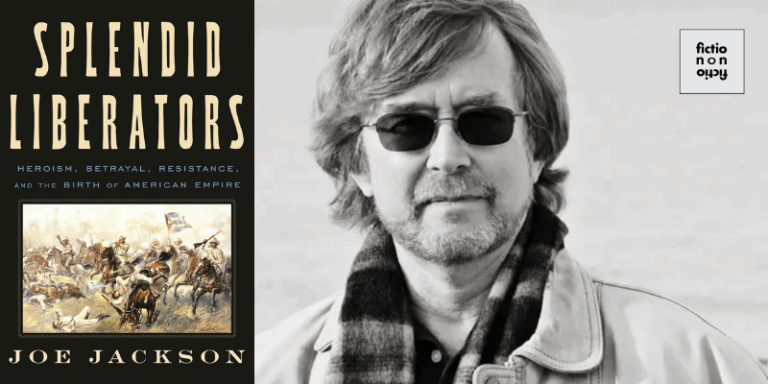

Award-winning nonfiction writer and former investigative journalist Joe Jackson joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about President Trump’s “Don-roe Doctrine” and his imperial ambitions in Venezuela, Cuba, Greenland, and beyond. Jackson, the author of a new book, Splendid Liberators: Heroism, Betrayal, Resistance, and The Birth of American Empire, explains how Trump’s plan relies on the template set by the Spanish-American War, through which the U.S. rose as a world power and ended Spanish rule in the Western Hemisphere. Jackson sheds light on the rhetoric that fueled the war, as well as the violent history of U.S. military interference in Cuba and the Philippines. Jackson takes us through iterations of the Monroe Doctrine and outlines the impact of that philosophy on Trump’s desire for imperial expansion as well as his authoritarian control domestically, in cities like Minneapolis. He discusses how the Spanish-American War served as a turning point for America’s soul, including writers of the time, and how it birthed a culture of war that has continued to impact the nation, its citizens, and the world ever since. Jackson reads from Splendid Liberators.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell.

The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Power, and the Seeds of Empire • Atlantic Fever: Lindbergh, His Competitors, and the Race to Cross the Atlantic • Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary

Other Books:

The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane • The Winning of the West, Volumes 1-4, by Theodore Roosevelt • Carl Sandburg • McTeague by Norris • “The Storytellers of Empire” by Kamila Shamsie – Guernica • Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph by T.E. Lawrence • Jose Marti Reader: Writings on the Americas • Noli mi Tangere (Touch Me Not) by Jose Rizal • On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin • Cuba in Wartime by Richard Harding Davis • The Essential Frank Norris, incl. The Octopus • Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson

Other Links:

Society of American Historians • Western Writers of America • True West Magazine • Monroe Doctrine (1823, archive.gov) • Roosevelt Corollary (19o5, archive.gov) • “Manifest Destiny” by John Fiske, March 1885 Harper’s Magazine Archives (subscription to read) • Trump’s Manifest Destiny – Project Syndicate • Library of Congress: “Remember the Maine!”

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH JOE JACKSON

V.V. Ganeshananthan: You’ve mentioned the writerly paths of many of the figures that you’re describing, who are also politicians or reporters, and you mentioned Stephen Crane. It’s been interesting to watch the press cover Trump’s grabs of power in Venezuela, Greenland ,and elsewhere. What role did the press play in legitimizing American action in the Spanish American War and also bringing it to an end? How was it described, and what kind of path did that lay for American empire?

Joe Jackson: The most famous reporters were in Cuba. They were only there for a very short amount of time, and many of them became quite famous. They were on the ground. They were trying to describe the conditions that the American troops fought under, and they described the charge up San Juan Hill. It was more bloody and more horrible than they had expected. Stephen Crane was already famous because of The Red Badge of Courage but that was all imagination. He had never been under fire.

Whitney Terrell: People often think that he learned to write about war in Cuba for some reason. But no, he made that up beforehand.

JJ: He went there because he wanted to see what it was really like and he was thinking of writing another book based upon his experiences in Cuba. But he died of tuberculosis only about a year after the war. What is interesting, though, is that you have some other Naturalists and some bitter writers coming out of that. Frank Norris was young.

WT: I was surprised to see him in there. He’s a really interesting writer.

JJ: He was. He was writing McTeague at the time that he was there but he radically changed it. He becomes very anti-capitalist. He writes The Octopus afterwards. I think Norris is fascinating, and he writes about just how awful war is. It’s not glorious at all, unlike the way that it is presented in the press. many times. Sherwood Anderson was not part of that group. He was part of the occupation afterwards. But afterwards, he writes Winesburg, Ohio. All of their voices are coarse, they’re not measured. They use language which is considered, at times, obscene compared to the literature beforehand. I think that you’ve got a real change in the way that American letters are presented by this core group of writers who were so prominent during the Spanish American War.

And what’s really interesting is not only does Hemingway cite the Spanish American War writers as an inspiration, but some famous literary, Hard Boiled writers like James and Kane cite those guys as their inspirations. This period changed American letters in many ways. In Cuba, they did extol American bravery, especially during the charge up San Juan Hill. But then they were appalled by the dearth of medical treatment that

these guys were getting. So, they helped end the war early because American soldiers were dying from fevers and other illnesses. In the Philippines, you didn’t have this clutch of famous reporters, and there was a lot more censorship. But the reports that got out focused on the inefficiency of the military, and the atrocities that were done against Filipino soldiers and Filipino civilians by American soldiers. That helped end the war faster.

VVG: One of the things I really appreciated about your book is that you did research in Cuba and the Philippines, and you illuminate some of the lesser-known histories or histories that have been obscured. This is a decolonial, or post-colonial, version of the Spanish American War and contained a lot of interesting character details about the people involved in these conflicts that I didn’t know. Kamila Shamsie wrote an essay that I often think about, published in 2012, called “The Storytellers of Empire” which takes to task American writers today for not really writing about the consequences of American “intervention overseas.” What does it mean? Who does it cost? As I was reading these sections, I was just thinking about this.

Also, I live, as our listeners know, in South Minneapolis. And I couldn’t help, as I was reading, thinking about the ways that this same narrative feels to me like it’s playing out domestically, the ways that the U.S. puts forward justifications for imperialism like the Monroe Doctrine that you’re talking about in the various corollaries. The idea that the U.S. is better, and it is here to save you. We’re going to come in; we’re going to fix it; it’s going to be fast; we’re prepared; no problem; in and out; you’ll be happy about it. That all plays really badly with the people at whom it is aimed. Do you think it’s fair to say that the same justification is now operating for Trump, not only overseas, but also domestically, with actions like the federal occupation of Minneapolis? The idea that “No ICE is here to save you. If you just cooperate and are appropriately grateful, everything will be fine. And those of you who are not cooperating with these extrajudicial murders, you must be corrupt.”

JJ: It’s really interesting that you use the Spanish American War as a metaphor for what’s going on now, and I think you’re right. We’re not talking Manifest Destiny. We’re not talking about taking over Minneapolis or Minnesota, but at the same time,

there’s the idea that “believe in our authority, because we know what we’re doing, and if you don’t believe in our reasoning, then you are corrupt.” That’s something that you saw very much in the Cuban side of the Spanish American War, and especially in the Filipino side of the Spanish American War, because there were so many Filipino civilians and soldiers who were killed in that war. McKinley even said at the beginning of the Philippine invasion that “We’re here to Christianize and civilize you” and his policy was called Benign Assimilation which Philippine scholars still laugh about.

WT: Soft murdering.

JJ: Yeah. It’s “if you don’t agree with us, you are mistaken. And because you’re so mistaken, you’re corrupt.” There’s a moment in my research which I have in the book, the Filipino government came up with a constitution and a government, and many people said that it was on a par with anything you found in the United States or Europe. The fellow who was pretty much the Thomas Paine/Thomas Jefferson of that movement, the fellow who wrote the Constitution, was a guy by the name of Apolinario Mabini. Mabini had been captured and thrown in jail after the war started and there were a series of letters that passed between him and a general by the name of Jay Franklin Bell, who was famous for a giant massacre in the province of Batangas to the south of Luzon, in which Bell basically said that “might is right.” If you’re in a war and you’re losing and there’s no way that you can win because of the overwhelming force of one side, then it is your moral obligation to surrender. And Mabini said, “Most Filipinos would laugh at you, because we don’t like this guerrilla war that we’re engaged in, but it was the only choice we had. And resistance to oppression is the greater indicator of a civilization than might being right.”

This is the philosophy behind these wars of choice that the United States embarks upon. They think that overwhelming force is going to win, but then the insurgency starts up, and it turns into a Forever War. I think ICE underestimated the people in Minneapolis, because they thought that there would be no resistance, but there certainly has been a lot of resistance. The one bright point in all of this is that you’ve got a large amount of resistance, people of all ages getting in the faces of ICE, you’ve got the poor guy who was the V.A. nurse, you’ve got the mother of three, people from all walks of life who are saying, “This is not right, and they’re standing up.” In a little nutshell, you’ve got an example of what was going on in the Philippine War. The outgunned continue to resist.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy.