Kayleb Rae Candrilli on the Cyclical Nature of Poetry and Healing

Kayleb Rae Candrilli’s poetry comes from a bedrock of resilience. From a hardscrabble childhood in rural Pennsylvania, as chronicled in the memoir-in-verse What Runs Over, Candrilli has emerged as a fearless voice on behalf of the trans community in particular.

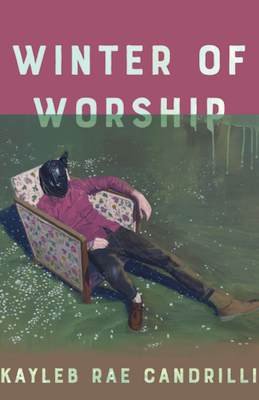

Their new collection, Winter of Worship, extends the threads of community care to the landscape of Philadelphia’s downtown streets. The poems grieve: for friends lost to the opioid crisis, for youth lost to climate change and the pandemic, for queer history lost to the AIDS epidemic. Yet Candrilli sustains a current of hope underneath, finding connection in the smallest gestures of the everyday. They indulge in the healing power of recursive poetic forms, using the repetitions of ghazals and “Marble Runs” to transform their surroundings.

Kayleb Rae Candrilli and I connected via email to discuss invented forms, emotional chronology, bearing witness through grief, and their ever-queer lens.

Skylar Miklus: I want to begin by asking you about the structure of the collection. The way the poems are placed next to one another feels so intentional. Even though the order of poems isn’t chronological, I feel like I can trace a storyline through the book with a cyclical type of movement. Can you tell me more about the overarching logic of the collection, as you see it?

Kayleb Rae Candrilli: When writing Winter of Worship, I wanted to push back against the kneejerk instinct to order narrative poems chronologically. Instead, I was interested in trying to craft an “emotional chronology,” which had its own distinctive arc.

Since an emotional chronology was what I was after, I think that’s why there’s a two steps forward, one step back type of movement to the book, or that “cyclical movement” you reference. Our growth, our grief, our love, hardly ever is, or feels, linear.

Digging into the minutia a little more, I have a rather extensive way of choosing the book’s order. I start by making a word cloud of the entire document. Then, I pull keywords to use as stand ins for the book’s most prevalent themes (usually around six to ten themes). Each theme is assigned a color, and I tag the top of each poem with the three most important themes contained in the book (in descending order of importance). When I lay the color-coded pages on the floor, I am able to see where poems have been thematically clumped, or where I’ve abandoned one of the book’s central themes for too long.

SM: Just as the book overall seems to have a recursive logic, you also employ poetic forms that feature recursive repetitions, like the ghazal. This inclusion of received form seems like a change compared to your earlier books. What drew you toward the ghazal, or toward repetitive form in general?

KRC: I like to joke that I tend toward repetitive forms because it gives me a permission slip to use a (hopefully) good line twice. And though I mostly say that jokingly, there’s some truth to it. So much of my writing feels instructive, but rather than instructive to an audience, it is intended to be instructive to me.

I wanted to push back against the kneejerk instinct to order narrative poems chronologically… to craft an ’emotional chronology,’ which had its own distinctive arc.

When I sink into the recursive or repetitive, I am trying to write myself a kind of mantra or mantras. My poems are written toward the person I want to be, rather than a person that already exists. Hopefully, and I think often, I am able to catch up to the poems.

As for this recursiveness being a departure from previous work, it is certainly a departure from my first two collections (What Runs Over & All the Gay Saints). But in Water I Won’t Touch I rediscovered my love of form with a sestina and a heroic crown of sonnets. I don’t think I’m alone in turning to form for the ways in which constraints can free us. When I started my third book, Water I Won’t Touch, I felt very stuck in the voice and cadence of my previous collection. Turning to form was integral in prodding my poetic voice along.

SM: You invented a new form of repetitive poem in this book, the Marble Run. In the “Notes” at the back of the book, you write about the form’s movement being inspired by a Jacob’s Ladder. Do you want to elaborate at all about how you visualized this formal structure?

KRC: I mentioned the heroic crown in my third collection (titled “Transgender Heroic: All this Ridiculous Flesh”). When I was working on that poem, I thought a lot about the movement of a Jacob’s Ladder, how a single piece of the toy cascades down the ladder in such controlled chaos. The movement of that toy is so like the construction of a crown of sonnets, how the repeated lines fall and reappear throughout the poem.

Visualizations like this are often helpful in my practice—a kind of synesthetic habit that feels very natural to me. When I took to making my own form, I was interested in using another semi-antiquated children’s toy to visualize the poem’s movement. I knew I wanted the form to be recursive, repetitive, like mountain switchbacks—so the marble run was an obvious choice for me in the form’s development and in its naming.

SM: In addition to structure, the other element about this book that really jumps out to me is the sense of place. The terroir of Philadelphia is all over these pages. What does your city mean to you, and how do you see the relationship between placehood and poetics?

KRC: It’s strange to me to have written a book so set in or motivated by Philadelphia, rather than the more rural spaces of my childhood and adolescence. But I suppose that illuminates some of the distance growing between me and where I come from, even if the distance is only time.

As with every place I’ve lived and worked, I am thankful for the ways I’ve been radicalized by routine institutional and governmental failings, and thankful too for the ways in which I have been taught and retaught tenacity by the people who have lived in the space longer than I have. I’ve lived in Appalachia, the American south, and Philadelphia, and in all three disparate spaces the aforementioned pattern remains just the same. Whether surrounded by evergreens, kudzu, or concrete those in power would have us suffer, and those suffering display herculean strength they ought not have to display.

As for the relationship between placehood and poetics, it is so inextricable. I am the product of my environments, and my poetics are the product of my personhood. But perhaps even more important than that, grounding my body in space adds a layer of reality to the work that I hope is important to my readers. I am not just trans and alive, but I am trans and alive at 16th and Wharton in Philadelphia, trans and alive on Thurston Hollow Road in rural PA, on the Amtrak Crescent line cutting through Alabama.

SM: The publisher describes Winter of Worship as a “book of elegy,” but I see the story as somewhat more complicated than that–it’s about both loss and connection. I admire the way the elegies remember both friends and strangers (i.e., the victims of the 2016 Pulse shooting). How do you think about the relationship between the practice of poetry and the work of grieving? Do you see part of the work of poetry as bearing witness in some way?

KRC: I wonder if there’s not much that separates loss from connection. By which I mean I feel so much connection to my lost friends and family. I still have meaningful connections with all my dead, and as often as that may be painful it’s nourishing, too. I don’t know if I’m doing a very articulate job of describing the sensation, but hopefully that makes a bit of sense.

As with every place I’ve lived and worked, I am thankful for the ways I’ve been radicalized by routine institutional and governmental failings.

As for poetry being a part of the work of grieving, it certainly is for me. I think it’s worth harkening back to what I mentioned earlier, about writing myself instructive poems. The poem written is where I want to arrive in my grieving; the poem is my map to get there, rather than an illustration of where I am at the time of writing. Grief, for me, is the messiest and most unstructured emotion. A poem can provide the scaffolding to help hold me up.

I’ve always considered bearing witness to be a crucial prong of poetry. I fall in a long lineage of poets who feel the same. But I often wonder if witnessing, on its own, fulfills what is (or will be) asked of us as poets. I think a poem that witnesses and names can be a successful one. But perhaps the poet’s life should be one more of action. We’ve seen it, we’ve named it, now what? I suppose I’m mainly thinking through this for myself and trying to figure how I might be most useful to the world and those around me.

SM: With respect to connection, I was touched by what I read as a set of love poems to your partner in this book. I love how innately and effervescently queer they feel, without thinking of the cishetero audience. How do you feel about audience—is it something you’re thinking about while writing?

KRC: I have only ever considered my queer audience, I think. I am writing both for and to my queer readers. Nothing could be more of a failure to my intended audience of queers, than considering cishetero comfortability or aesthetics.

This isn’t meant to be alienating in the slightest; in fact, I think most cishetero readers of my work might appreciate that it isn’t written for them—as so much of art and the world is made with them in mind. If they’ve found my work, it’s because they want and perhaps need an experience outside of themselves. And of course, I am so grateful to any and everyone who spends some of their finite time on earth reading my poems. What an incalculable honor.

SM: Overall, it feels to me like this book is cherishing the community you have around you. I was affected by the reference in “Poem for the Start of a New Decade” to the support surrounding you during your top surgery recovery. How does your community influence your artistic practice?

KRC: The line I believe you’re referencing is, “Everyone I know / pitched in to help me remove my breasts / with a scalpel.” More than I think about how my community influences my artistic practice; I think about the ways in which it’s kept me alive to make art at all. It’s community that’s kept many of us alive. It will be community that keeps us alive moving into an even more uncertain future.

SM: To close, please feel free to tell me about any texts that felt like influences or part of the book’s lineage.

KRC: There’s so much music behind this book, especially music of a nostalgic ilk. I put together a playlist you can find here!

And I just wanted to shout out a few things I’ve been spending time with as of late! I’ve recently discovered Sophie Calle’s work, specifically True Stories and Suite Vénitienne. I am so entranced and captivated by her projects.

Gregory Halpern’s photo collection King, Queen, Knave knocked my socks off. And I’ve been doing a deep dive of Jim Jarmusch’s films lately. My favorites so far are Only Lovers Left Alive and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. Lastly, I am rereading the late Aziza (Z) Barnes’ i be, but i ain’t.

The post Kayleb Rae Candrilli on the Cyclical Nature of Poetry and Healing appeared first on Electric Literature.