Lit Hub Asks: 5 Authors, 7 Questions, No Wrong Answers

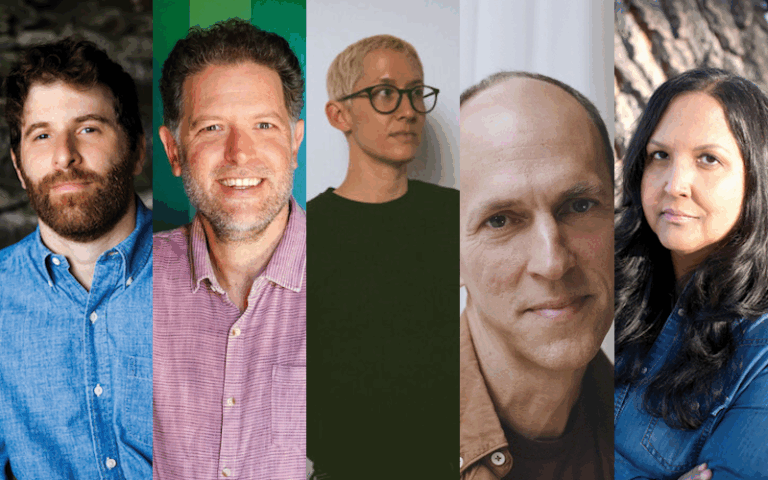

The Lit Hub Author Questionnaire is a monthly interview featuring seven questions for five authors with new books. This month we talk to:

Jonathan Bernstein (What Do You Do When You’re Lonesome The Authorized Biography of Justin Townes Earle)

Stefan Merrill Block (Homeschooled: A Memoir)

Davey Davis (Casanova 20: Or, Hot World)

Ben Markovits (The Rest of Our Lives)

Nina McConigley (How to Commit a Postcolonial Murder)

*

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Ben Markovits: The desire to lead a secret life. The desire to not lead a secret life.

Davey Davis: The dark side of pretty privilege and the loneliness of self-actualization.

Jonathan Bernstein: The stories we tell ourselves about the relationship between art, creativity, suffering, and self-destruction. And what it was like to have grown up in a specific two-mile radius of Nashville—south of downtown—in the Nineties.

Stefan Merrill Block: Mom, childhood, loneliness, escapes both imagined and real, inherited trauma, Harriet the hamster, the wide blind spots in homeschool law, puberty, family, ’90s nostalgia, Mom.

Nina McConigley: Murder. Postcolonialism. Girlhood. Language. Sisters. Partition. Wyoming and the American West. A 1980s version of *Little House on the Prairie* if Ma were brown.

*

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Nina McConigley: Seventeen magazine. The Royal Family. The Challenger explosion. Sleepaway camp. Esperanto. Antifreeze. Halley’s Comet. Hands Across America. Chernobyl. Ouija boards and Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board. And the British.

Jonathan Bernstein: My wife’s work as an editor. My father’s love of music. My mom’s and sister’s work as social workers. The music of Billie Holiday and Great Grandpa’s *Patience, Moonbeam*. Newspapers.com.

Davey Davis: Casanova 70 (1965) is an Italian comedy about a man who can’t get it up unless his life is in danger. It stars the gorgeous Marcello Mastroianni as a lover whose masculinity is so successful that it almost ungenders him. How could I not write a book about this?

Ben Markovits: Road-tripping, middle-aged friends, middle age. Kids leaving home.

Stefan Merrill Block: My wife and my daughters. My father and my brother. “The Sunset Tree” by The Mountain Goats. Therapy. Older Spielberg films, especially those with lonely child heroes. Seeing my kids at their schools. Mom.

*

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Jonathan Bernstein: Wedding planning, first year of marriage, all my friends getting married, working at my day job, trying to find time for everything and everyone.

Ben Markovits: Road-tripping. Sickness. Basketball podcasts.

Stefan Merrill Block: Early fatherhood, grief, moving upstate, purchasing a roller rink with friends, fixing temperamental arcade machines, changing ten thousand diapers (an actual estimate I just made with a calculator).

Davey Davis: When you finally have a reason to live. Everything becomes about death.

Nina McConigley: IVF. A pandemic. Lockdown with a newborn. New motherhood. A move to Colorado. Writing a play. Slogging to tenure.

*

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Stefan Merrill Block: With my second and third books, people took me to task for my frequent use of high-vocab words and elaborate sentence structure (“wordy” was the common diagnosis), which especially irritated me because I read that as a more general accusation of pretentiousness. But then I look back at the writer of those books, typing away his twenties and early thirties in his Brooklyn solitude, and actually his pretension annoys me too.

Nina McConigley: Immigrant narrative. Quiet storyteller. Goodreads says I have too many confusing (non-American) names.

Davey Davis: I get pretty pissy about the identity words used to market and discuss my fiction. I’m not nonbinary, and nor are any of my main characters, but that one gets thrown around a lot. I don’t mind “queer” in and of itself, but I hate its use as an adjective, as in, “This book is very queer.”

Jonathan Bernstein: As a first-time author, I can’t wait to find out!

Ben Markovits: I don’t know if there’s a word, but maybe a tendency. At my first book event for my first novel, The Syme Papers, I sat in a small room in front of an audience of five people: my wife, a friend, my publicist, and two actual punters, as the English say. I read them a scene where my narrator drives home to clear out his family house in San Diego after his father’s death. One of the punters raised his hand and said, “I watched my mother die. I watched my father die. Why should I pay to watch your father die?” His mobile rang while I was answering, and he took the call. I was trying to explain to him: my dad is fine.

*

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Davey Davis: I have a day job already, but I think I would do well as a mail carrier or psychoanalyst. I’m also great with old people.

Jonathan Bernstein: Irrespective of talent? Backup point guard for the Knicks, retired by 40.

Ben Markovits: Basketball reporter. I’m actually still waiting for the call…

Nina McConigley: Gin distiller or Episcopal priest. Both tend to the spirit.

Stefan Merrill Block: I wish I had at least semi-seriously dabbled in archaeology. I never even took an archaeology class! Which is a shame because ever since early childhood, nothing gets me more excited than tromping around through ruins, feeling so close but also so far from the hands that built the place. I sometimes get a little hit of that same thrill at garage sales.

*

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Nina McConigley: I love the first person. And I am amused by punny names. Being biracial, I have learned to see both sides of things since I was little, which has helped my writing. Still working on plot. Every time I read an *Agatha Christie* novel, I think: damn, she could plot.

Stefan Merrill Block: I feel most comfortable when I’m channeling any character who is not quite myself—or at least not myself in my current, middle-aged version. After four books, I’m still learning that I need to trust the reader, that I don’t need to open a story with a PowerPoint presentation on who each character is and what they’re after.

Davey Davis: On my better days, I fancy myself a stylist. I’m not so good with plot, especially endings.

Jonathan Bernstein: Going into this process, I felt most confident about my ability to pull off the hard journalism skills—researching, reporting, corroborating, getting multiple sources whenever possible, making judgment calls about attribution—that I use in my day job as a researcher and fact-checker. I felt least confident, and would most like to get better at, the actual, uh, writing part: structure, voice, rhythm, narrative, character development, all the things that make great nonfiction writing. I strive to get better at all of those things!

Ben Markovits: The kind of quiet realism I try to write sometimes makes people seem unhappier than they really are. I’d like to get better at writing happiness. That seems like a craft issue—how to build plots around happiness.

*

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Jonathan Bernstein: If only I had such hubris to contend with! If I did, I’d counter it by focusing on the interest readers might have in the subjects I write about, rather than my own writing in a vacuum.

Davey Davis: Writing is my way of being with other people, so I don’t see anything inherently hubristic about that. I also think taking pride in one’s work is healthy. Sexy, too. Why shouldn’t people—some of them, anyway—be interested in what I have to say? I’m interested in them. That’s the point.

Ben Markovits: It doesn’t worry me much when I’m writing, on some rainy Tuesday morning, when I’m alone in the house, because the prospect of being read seems far away. But afterward, when the book comes out, I contend with this feeling mostly just by feeling bad about it.

Nina McConigley: Because so few people write about Wyoming. Is it even real?

Stefan Merrill Block: Honestly, I try not to expect that anyone will be (or should be) interested in what I write. I once spent years on a novel that I couldn’t find a publisher for—a hard experience, but it also showed me that regardless of how my work is received, I’m just going to keep on writing because it feels necessary for me. If people decide what I write has value in the world at the moment, of course that’s great news, but I do my best to separate my writing from the expectation that other people will necessarily be interested.