“Local Specialty”

The fog is unreasonable—thick and too chilly for summer—on my morning bike ride to Bertha’s Breakfast Buffet, where I’m lead server and manager. When I cross the bridge to town, it feels like I’m about to roll right off the edge of the map. I edge closer to the center of the lane.

A car swings out of the fog. By the time I see it, it’s honking and swerving, clipping my backpack.

I screech to the side. I flip off the car, but it’s already sunk back into the gray.

Then a much deeper honking, baritone, comes up from underneath me, like the earth is honking back at that Lexus asshole, taking my side. The sound shakes the bridge.

A tanker—close.

The big ship slinks out from the fog. It’s like a cathedral has snuck up next to me: a building bigger than any in town. Massive, wide, tall, and red, with condensation rolling down its immense facade. The tanker is so big it fills my field of vision. There’s some foreign script that makes me think of Cyrillic, almost.

I stop pedaling to stare. I’ve always liked the tankers.

They come from so far away—Panama, the Marshall Islands, Liberia—farther away than I’ve ever been. I scan the rusty castle of the tanker, looking for someone to wave to. There—on a deck so high it’s almost lost in the fog—a few skinny sailors are waving back. I can’t make out their expressions, but they are swinging their arms in perfect unison, so perfect it almost looks like a dance. Maybe they are all listening to the same song; only I don’t hear any music.

Swish, swish, swish.

I match their cadence; it’s easy. In fact, it’s almost irresistible. I don’t speak their language, so this feels like the least I can do. Swish, swish, swish: You’re stuck in your dead-end job, and I’m stuck in mine, halfway around the world. But for a moment, we acknowledge each other.

The tanker turns into the narrow channel leading to the port, and disappears again. The sailors are still waving as I lose sight of them.

I’ve lingered too long already. I kick off.

*

I aim to get to Bertha’s first, lock my bike, unlock the door, punch in the alarm code, and start three pots of coffee brewing. From 6:00 a.m. to 7:00—the hour before customers—is my favorite part of each day. Cesar, our high school–aged cook, says I am a misanthrope. He’s probably right. The restaurant without people in it is so lovely. It will spend the rest of the day devolving into ruin: syrup on the floors, home-fries grime under my fingernails, running out of raspberries.

I refill the ketchup bottles and pickles from our supply in the basement. I pull the butter tabs out of the freezer to defrost on the counter. I’m twenty-six, and I don’t remember when but my life has become pocket-size: just something I carry with me on my routines, shrunk down by wage labor and rising rent. I peek at it every once in a while before tucking it away again. Back to work. Maybe I should find my way onto a tanker, stow away, and reinvent myself in the Southern Hemisphere.

Cesar arrives at 6:50. He nods to me without taking off his massive headphones, lights the griddle, and makes me a breakfast sandwich just how I like it: Canadian bacon, charred English muffin, melted American cheese. “It takes three nations to make your perfect sandwich,” he joked once. It took me a minute.

Cesar is smart. He has a favorite poet, and he remembers every regular’s order. He invented a new dish: Eggs Cesar, which is poached eggs over basil and green peppers and cornmeal cakes. He never gets flustered by a rush—he enjoys the puzzle of negotiating twelve orders at once, all with different cook times. He’s working at Bertha’s to save up for his freshman year at UNH. I’m glad he has a plan: someone like Cesar shouldn’t get stuck here.

Cesar puts my sandwich in the window and rings the bell, even though it’s just us.

It’s 7:00. While I’ve been going through my routines, the coffee’s finished brewing. Three dark crystal balls are swirling and simmering. I have to unlock the doors.

Jules and his husband, Cristian, are waiting in the alley. No surprises there. They spend their summers here; seasonal regulars. Jules and Cristian aren’t even that much older than me, but they’re in Brooks Brothers while I’m in a washed-thin Siouxsie and the Banshees T-shirt.

“Did you hear? Literally or figuratively?” Jules asks me. He’s an adjunct professor at one of the Boston schools. He and Cesar would have a lot to talk about, if Cesar could ever get out of the kitchen.

“What?” I ask.

“A tanker hit, ran up on the rocks in the fog. We heard the boom from our rental.”

My tanker, my sailors. I picture them waving. I hope they are okay.

“They suspect a spill,” says Cristian.

“A spill of what?” I ask.

They give me a funny look. Probably this is a dumb question. Fuel, right? But I read a story once of a molasses spill, and another where a container ship dumped Nikes all over the coast of Washington. I could use a new pair of shoes.

Jules shrugs. “I guess we’ll find out. Coffees?”

“Coming up.”

Soon, the 9:00 a.m. rush shoves aside my thoughts of the tanker. The other staff clock in and get to work. I’m taking orders and clearing dishes and wiping spills and refilling coffees and brewing more and running back to the window every time Cesar rings the bell. All smiling: at the end of the day, my cheeks will be sore.

Bertha’s vibe is small-town and quaint, like a place frozen in time. Except that we’ve changed immensely. Now that tourists from Boston and beyond have discovered the town, we charge them as much as we can get away with for muffins and scrambles. No one local comes anymore. The tourists take photos with the lobster traps on the ceiling.

Our hollandaise is made from a powder. I’ve sworn Cesar to secrecy.

The owner lives out of town—cheaper for him that way—and only comes by every month or so to check on things.

I tried a few other things, driving deliveries and dinghy tours of the port. But, with tips, I make as much as my friend who teaches elementary school, and she has student debt and a master’s. With rents going up, Bertha’s is enough to keep me afloat, barely.

Around 10:00 a.m., we hear sirens and see red flashing lights through Bertha’s big front glass windows. Everyone pauses for a moment to watch, forks hovering over their plates. Then we go back to our roles. I laugh at the tourists’ jokes and give them directions from their Airbnb to the beach access.

“No lobster?” The customer at table eight gestures past me with his menu, toward the specials chalkboard. He sounds affronted.

“Sorry, all out,” I say. What I don’t say is that our coast is one of the fastest warming places on the planet. Tourists don’t want to hear all that. It’s a downer. We’d love to serve lobster, but locally caught are rare and expensive. I can’t even remember the last time I had a lobster roll. It’d be like eating dollar bills. Nothing tastes that good. “But our special benedict today is fiddleheads.”

“Fiddleheads? What’s that?”

“Local specialty!” I say. “Imagine asparagus. Delicious. Seasonal and grown locally.”

“Organic?”

“Of course.”

On the specials board I’ve drawn fiddleheads as little green swirls, like the tentacles of a sea monster.

“Sure. Why not?” He leans into his wife. “Something exotic.”

I smile. I hope he thinks I’m laughing with him.

Fiddleheads are a fern. They look fancy. I think they taste nasty: bitter and slimy. But they make for a great Instagram photo: green swirl peeking out from underneath a yellow yolk. Proof someone went on a trip.

In season we can get fiddleheads for cheap, fifteen dollars a pound, then drizzle some hollandaise and smoked paprika on them and charge that much for a single plate. No local would pay that much for a fiddlehead; they’d laugh in your face. Fiddleheads are a shibboleth; Cesar taught me that word last week. He’s studying for his SATs.

“Is Bertha around?” the customer asks.

“She’s out today!” I say. “Just missed her!”

As far as I know, there never was a Bertha. The closest thing we have is the mascot hanging on our wooden sign above the door: a crusty mermaid holding a carved spatula, flipping some bacon. Her paint is chipping.

*

Bertha’s closes at three. I want to go see the tanker, but an exasperating party walks in the door around 2:50. They take their time; they order mimosas. I’m finally rid of them around four. Half an hour later I split the tips and wave bye to Cesar. “See you here tomorrow.” Same thing over again.

By the time I’m finally free to bike over to the wreck, most everyone has left. The tanker is still in the water, a little off-kilter, a little too nestled in the rocks. There are wide, thin nets trying to keep in— what? Some contaminants I can’t see. It smells like cinnamon and paint thinner.

Next to me a seagull coughs. I didn’t know they could do that. Everything is poisoned, probably: the rocks, the air, the water. Sayonara to the few lobsters that are left. That seagull’s days are numbered.

There’s the WMUR News 9 van, filming some footage for the evening news. I get a funny idea and I swing my bike and my body into their shot, between the camera and the tanker in the background. I start waving my arms in the same slow rhythm of the sailors from earlier that morning. Swish, swish, swish. I don’t know why I do this. Just—I have this idea that the sailors might be watching. I picture them in the ER, wrapped in those thin silver blankets they give marathoners and bombing victims, here in this cruel foreign country where no one speaks their language. I want them to know that I remember them, that I’m worried about them.

While I’m waving, I hear the reporter mention the yacht.

“A yacht in the shipping lane.” He says the tanker swerved to avoid the yacht, and BOOM. That’s what caused the wreck and the spill of Lord knows what. A fucking yacht.

Just a playground to the tourists. But we live here. It’s our livelihood and our home. Most of my friends from high school have already been priced out. I’m barely hanging on.

I get jittery with anger. But what am I gonna do? There’s no bad guy to fight. I just keep waving. Up and down, up and down. The reporter tries to scare me away, but I bike a little farther and keep waving, swish, swish, swish. I won’t let them get a clean shot. They’ll have to use what they got.

*

Soon the tanker is towed away. On TV, local marine biologists are concerned and local environmental activists are enraged, but mostly, life goes back to normal. “We won’t know the long term effects till . . .” The news stories slow. I add the yacht and the crash and the spill to my register of simmering offenses. I go back to my routines.

Except on one of my morning rides into Bertha’s, I do see something along the ocean road. Around 5:20, a black van with no windows is parked with its back to the water. A couple of men on walkie-talkies are standing next to the van with their ties blowing into their faces. They are watching scuba divers in fancy all-black gear walk backward into the water, step, step, step, carefully over the slippery rocks.

I keep biking, no time to stop. But I glance over at them. The divers sink under. I’m happy—someone is going to do something to fight the spill. To look after the waters.

As I pass right by them I can see into the van, a little, just for a second. I see a speargun, as tall as me. The image lodges in my brain like a splinter, but I can’t be late. I’m the one with the keys to Bertha’s, and there’s no way I’ll leave Cesar waiting for me in the alley.

*

Every once in a while, as summer’s beachcombers turn to fall’s leaf peepers, I think again of the tanker and the spill and the sailors and the strange van. But it’s not till winter, when the town empties out and business turns slow, that Cesar and I go to the shore together.

All Cesar’s studying paid off. He got a scholarship to UNH. But every weekend day he’s still at Bertha’s frying eggs. He’s got to save up for books and food and housing.

One of those weekend days is so unbelievably slow that we’ve already sent the dishwasher home. We make pyramids out of the red plastic cups; up to six levels high before they tumble down. I wash the front windows and Cesar cleans behind the stove—all the bottom-of-the-list tasks. Cesar films us taking shots of hot sauce and horseradish, and we stand in the kitchen counting the likes and reading the comments to each other. Still no customers.

“Can we get out of here?” Cesar asks.

Well, why not? We’re not making any real money today.

I write, “Gone fishing,” on the back of a paper placemat and tape it to the front door. We grab our jackets.

Cesar stands on the back of my bike; it’s not far to the shore. At first I was embarrassed to tell him I didn’t have a car, but he’s always been cool about it. “Very eco-conscious of you,” he said.

We find a cove to hide us from the road and settle in to watch the lapping waves against the rocks and smoke blunts for a while. It is overcast and chilly, but that means no one else is around. Our cove shields us from the wind.

I sit far away enough from Cesar to make it clear that I’m not hitting on him or trying to get him too high or anything. I’ve met enough creeps in my life to be wary of acting like them. Cesar’s clever enough, I hope, to avoid the traps I fell into, to get out of this town, clever enough that if he’s choosing to spend this free day in my company, then maybe I’m not so bad after all.

The weed is kicking in and I’m having all these nice syrupy thoughts. Despite the cold, it is cozy, nestled into the rocks. I’m thinking that the way Cesar trusts me makes me want to earn that trust, to be a better type of person. Cesar doesn’t think I’m a fuckup. I’m getting dangerously close to saying this corny shit out loud to Cesar, so I look out at the water instead.

“Hold up,” Cesar says. He points over my shoulder.

I turn around. It’s just a lobster, on the rock above and behind me. “Little buddy must be stoned too,” I say.

That makes Cesar laugh.

It’s not normal to see one so close, or so far away from the tide.

“Hey, there’s another.” I point to a rock in the distance. A lobster is waving its antennae around and looking a little lost.

Like one of those Magic Eye pictures, now that I’ve seen two, I see them everywhere. What I notice first is all the antennae, each attached to its own lobster, tapping out the same beat, like a metronome, up and down, in sync. There must be twenty, no, forty—more. We are surrounded. Some are between us and the bike, which I left back up near the road. Some are near and some are far. Every third rock or so has a lobster on it. Blue-black and chunky, gnarled. The same color and slickness as the rocks around them. And those antennae: bouncing along to some beat they can hear that we don’t, some lobster frequency.

“I thought the ones that were left had died off after the spill,” Cesar says. He is staring out at them and frowning. He starts rubbing his hands, like to warm them, in the same rhythm as the antennae. Does he notice?

“Not these ones,” I say.

“I guess not.”

“Maybe they’re special. Hey, man, don’t fuck with it,” I tell Cesar, but he is already bending down to pick up the closest one by the tail. Maybe I’m high; maybe I’m paranoid—but my stomach clenches. Cesar is smart, but I have this feeling that is a real dumb idea.

“I just want a closer look,” he says.

The lobster Cesar is reaching for is just sitting there twitching. Then it scurries, but not away—toward Cesar.

Wrong again. Something is wrong.

On every rock, the lobsters start moving at the same time. One single lobster crawling on a rock barely makes a sound. But all of them, at once, is loud: close and fast.

Next thing I know, my pants and sleeves are heavy, and wet. I stand up and lobsters are swinging from my clothes by their pincers. I’m kicking and shaking while I scramble on the rocks toward Cesar. I don’t want them to touch my bare hands or my face.

Cesar is a step ahead of me, rushing out of the cove and back toward the bike. In his rushing he missteps. He catches himself with his hands against the rocks; doesn’t hit his head, but the lobsters crawl onto his arms from all sides, over each other. I slap one off his shoulder; I hoist him back on his feet. Another one is climbing up his leg. Fuck. I grab it by its tail and fling it back toward the water.

We’ve got to get away; we can’t keep swatting at them. There’s too many. For every one we fight off, three more crawl up behind it. We have to run.

“Go!” I yell to Cesar. If we can make it to the bike, we’ll be out of here. We can’t stop moving, even to shrug them off. They’re acting like a swarm, like ants or bees. Coordinated attack. Their carapaces crunch, sturdy under my sneakers. From a distance we must look mad; high-stepping and kicking and flailing our arms, trying to shake them off, wave after wave. Thank god for the bike. When I throw one leg over, there are still some lobsters hanging off of me, but I start pushing my weight into the pedals.

“Get on!”

Cesar doesn’t need convincing. He’s on, hugging my shoulders and panting.

We take off, still hauling a half dozen lobsters, clinging to us like ugly brooches.

I push us into the cold wind, away from that cove. I don’t look back. But Cesar does.

“They’re still coming.”

“For real?”

“They won’t catch us, but they’re coming.”

None of this is how lobsters act.

As soon as the cove and swarm are out of sight, I pull over under some bare trees. I rip off my jacket. It’s frigid and my arms and legs are wet, but I can’t stand to have those things on me one more second.

“Fuck was that?” Cesar asks me.

We’re still on the bicycle. My jacket is squirming on the ground where they—two of them—are trapped in the folds. I step off the bike, willing myself to go toward them. I raise my boot to stomp the whole situation, but Cesar says:

“Wait.”

“What?”

“Just a minute.”

So I wait. The jacket and what’s inside it twitch on the ground. A clueless car rips past.

We catch our breath.

*

Cesar convinces me to bring the bundle of freak lobsters and jacket back to Bertha’s. For a “test.”

“They’re weird, right?” he says.

“Yeah. But I don’t want to touch them.”

“I’ll hold them,” he says, and he does, cradling my wet jacket the whole way back, tight.

Back at Bertha’s, Cesar sets up these experiments while I brew coffee.

We dump one in a cardboard box and another in a trash bin, a room apart. When he kicks the trash can, the one in the box shudders. Some strange solidarity. Cesar’s looking at it like a scientist, but I’m staring at the lobster in the box, on the floor of our kitchen, and a different idea comes to me.

“What do you think it tastes like?” I ask. “What, are you gonna try some?” Cesar says.

“No—not me.” We’ve bested them once. We could do it again. Cesar is frowning, thinking.

I fill the quiet: “The brunch crowd. It won’t hurt anybody. Probably.”

Finally, Cesar says, “These lobsters are doing fine. Better even, than before.”

“Right.”

“Like super lobster.”

“A health food!”

*

It takes us a few weeks, but we figure it out.

We go back to the cove. I’ve never seen them anywhere else, but we find them at the cove every time. We try the lobster traps from the ceiling, once, but that doesn’t work without a boat. Eventually we figure out a way to swoop a dozen of them on a single trip. We use my bike and some gear from Bertha’s—milk crate, kitchen trash bag, broom. Cesar hangs off the back of my bike. He holds tight to the trash bag, which squirms with a sickly rhythm, like one big heartbeat.

At Bertha’s we store them in the basement, each in its own bucket of cold water, each with something heavy on top: a crate of tomatoes or a sack of potatoes.

By summer we’ve got it down to a routine. A new routine. One that makes the world seem bigger, not smaller. Lobster’s back on the menu at Bertha’s.

I slip down into the basement to pull one from its bucket. All of them snap at me in lazy unison, their mystical beat.

Upstairs I pass it to Cesar; he stabs it in the middle of the forehead. Once it’s cooked, white and pink and covered in butter and hollandaise, you’d never know it was any different.

I sprinkle some parsley on top and head out onto the floor. It’s only 10:30. We’ve already sold fourteen plates of the lobster benedict, at $19.99 a plate before any tip, and we aren’t paying a cent for the meat.

We are making a killing, pure profit, under the table. We’re catching the lobsters ourselves. The owner doesn’t know a thing about it; we’re pocketing the profit: Cesar’s idea. He said to me, “Those things you want for me, I want them for you too, man.” So we’re splitting it fifty-fifty, the extra work and the extra profit. There’s no deliveries to check off, everything’s off the books. Cesar will have his college fund, and then some; I’m saving to get out. That’s as far as I know. Bertha’s isn’t forever anymore.

No one retches; no one shivers. No one’s eyes roll back in their head. Only, I swear to Cesar, later, as we’re closing up shop that day, that there was this moment when everyone who ordered the special reached for their napkin. They unfolded it slowly, one, two, three, and wiped their mouths, left to right. Then they set it back down on their lap, all at once, in perfect unison.

__________________________________

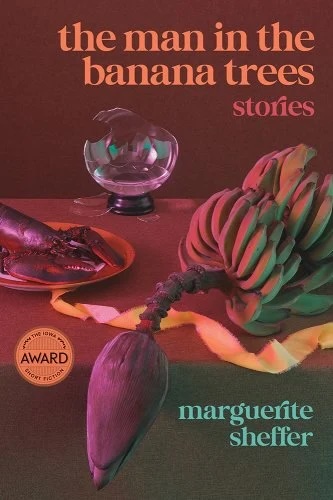

From . Used with permission of the publisher, University of Iowa Press. Copyright © 2024 by Marguerite Sheffer.