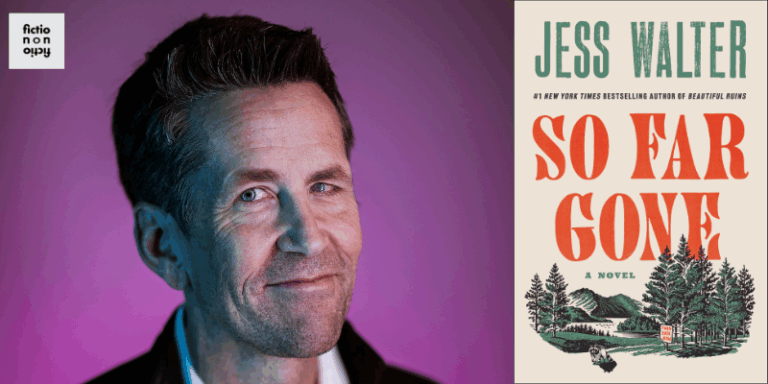

Jess Walter on the American Family Unplugged

Fiction writer Jess Walter joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new novel So Far Gone, in which a former environmental reporter living off the grid is jolted back onto it by the surprise arrival of his two grandchildren and news of his missing daughter. Walter talks about developing the character of his protagonist’s son-in-law, whose right-wing politics are one of the causes of the family’s fissure. He also reflects on what it means that conspiracy theorists, who were formerly at the fringes of American politics, are now at its center, and why it is important for writers to depict the interior lives of those with different political beliefs. Walter reads from So Far Gone.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/. This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Hunter Murray.

*

So Far Gone • Beautiful Ruins • The Cold Millions • We Live in Water • The Angel of Rome and Other Stories • The Financial Lives of the Poets • Citizen Vince • Ruby Ridge: The Truth and Tragedy of the Randy Weaver Family • Over Tumbled Graves • Land of the Blind

Others

“America’s ‘Spot News’ Novelist Takes on the Trump Era from Spokane” Washington Post • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 1 Episode 6: “All the President’s Shakespeare: Jess Walter and Kiki Petrosino” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 4 Episode 4: “Life After Trump: Jess Walter and Jerald Walker on the Aftermath of Election 2020” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 8 Episode 5: Jess Walter on the Election ‹ Literary Hub

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH JESS WALTER

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So just there are many voices in your new novel So Far Gone, and we’ll get to that as we go on, but the first and arguably most central voice is Rhys Kinnick. And I wonder if you could just tell us a little bit about him to start us off.

Jess Walter: Rhys came out of the idea you guys were talking about for me, which was, I had seen this New Yorker cartoon of a car racing along the freeway, and ahead of it said, “Can’t Look Away.” And then there was this little off-ramp that said, “Had Enough.” I’m such a news hound. I was crunching data all through 2024 looking at the precinct level, watching politics. And at some point, I just got so fed up with it that I thought, what would happen if you just threw your smartphone out the window, the way Rhys does, watched it bounce in the median, and then went off the grid and stepped away from it all. Rhys is a former environmental reporter for a local newspaper. I was a newspaper reporter for about seven years, and still think of myself in many ways, almost as a spot-news novelist. So, I’m still drawn to write stories as they’re happening.

It was very easy at first for me to inhabit this character, Rhys, and then fill him with the rant that I find myself perpetrating in my own head all the time. And then, as always happens with fictional characters, the political becomes personal, and you start knowing much more about this cranky old guy who has moved up to the woods and spent the last seven years doing nothing but reading books and writing an incredibly ambitious book called The Atlas of Wisdom that he thinks is going to be the thing that people remember him by.

Whitney Terrell: I mean, that does sound like what I’ve been doing for the last seven years, just not in the woods, or like every writer in some ways. Anyway, Sugi and I were talking about in the opening, families matter, especially if you’re thinking about going off the grid, and the book opens with Rhys in his cabin discovering that his grandchildren, Leah and Ash, are at his door. So just to give us a shape of the book as we talk about its issues, how did they get there, and who are the other important members of Rhys’s family for our listeners?

JW: That was the first image I had was this guy living in the woods and two kids showing up on his porch. I needed something that would shock him out of his paralysis, out of the fact that he has dropped out of the world. I’m probably an over attentive father. Sometimes you’ll create a character out of pieces of yourself or something you’ve thought or even a career, and then when they depart from you is when it’s most interesting. So, imagining that Rhys has only seen his grandkids once in the last seven years, and he doesn’t recognize them when they show up on his porch.

The book begins right there: he looks out of the porch, sees two kids and ask if they’re selling magazines or chocolate bars for their school. Of course, they’re neither. They’re his grandchildren and from there it seemed like a really straight path to him having to recover his family. I think all of us have checked out in some way, but I wanted to write a sort of heightened version of that, checking out and then thinking, what would draw me back? The thing that would, I think, that draws any of us back is family. What has estranged Rhys from his family is that he’s punched his son in law, a guy named Shane, who has followed AM talk radio all the way to its illogical conclusion, which is the sort of Christian nationalism that we find all over the country now. He belongs to this church, the Church Of the Blessed Fire, which has a men’s group called the Army Of the Lord, which Rhys keeps mistaking for his old email address, AOL, and that’s what starts the thing going. Then his daughter, Bethany has disappeared, and a friend has brought the grandkids to Rhys, and that’s one of the reasons he didn’t recognize them is that they’re with a different woman.

But that’s what gets the action going, and really what drives it is Rhys trying to find out where his daughter’s gone, why these suddenly abandoned children are on his porch, and to deal with the thing he left behind when he punched his son in law at Thanksgiving in 2016 which is the fissure in this family that may be irreparable.

VVG: Interesting. I was thinking as I was reading this book about all of the children’s books where the children are by themselves, as is really helpful sometimes in children’s literature, and then they find the grandparent, like The Boxcar Children, or Dicey’s Song. And I never really thought about… what is it like on the other hand when your grandchildren show up? You mentioned the figure of Shane, who is a white nationalist who thinks that the NFL is being rigged by globalists. It’s very hard to write about people like Shane.

WT: Is the NFL not being rigged by globalists? Is this something?

VVG: Oh, my God we’re breaking into it right now.

WT: Everyone who’s not a Chiefs fan certainly thinks that. I believe that the Chiefs win on pure talent, but I’ve heard some other people thinking differently.

JW: I mean, if that’s the case, then they’ve only done football. Because I think the royals are still on the other side of the grand conspiracy.

VVG: It’s hard to write about people like Shane, who believe in such improbable concepts, and yet they’re totally adamant about and committed to their— air quotes on this— truth. So how do you make a character like that three-dimensional? Should you? How did you think about that?

JW: I guess one of the big problems for me is that we almost can’t imagine what people on the far other side of the spectrum think. And as novelists, if we can’t imagine that, that feels like a defeat, that feels like surrendering in some way. My career sort of began— my writing career— writing about people on the far right, in the fringe. There’s a moment in this book where Rhys finds his old editor and says, “Who’s covering the radical right now?” and his editor says “The government reporter.” These ideas that, when I wrote in 1992 about Ruby Ridge, were on the fringe, or so much in the mainstream, and I think the biggest reason why has to do with Rhys’s old career. Rhys was a journalist, and we have eroded every establishment; every source of knowledge and information, trust has been eroded in it. The media is just one of them. Now, half or more of Americans get their news from social media. And of course, they’re not really getting news, they’re getting conspiracy theories, they’re getting reinforcement of what they already believe.

But to write about a character like Shane is no longer to write about a fringe character. One-fifth of Americans believe that the COVID vaccine implanted microchips in your body. The same number believe that the US government was behind 9/11. These are conspiracies that drift back and forth from far right to far left. One of the things that sparked the novel was having some reasonable friends tell me that that the NFL was rigged in this conspiratorial way,

WT: And I just want to point out it’s not.

JW: It was not rigged then, Whitney. Although when the Chiefs’ run is over, you can get back with me.

WT: People felt that because Kelce did a Pfizer commercial, right? Those things matter to people.

JW: We live in very conspiratorial times and the scariest thing is, 40 percent of Americans believe that no matter who’s in charge of the government, there’s really a secret cabal of shadowy forces running it. The effort to undermine our institutions has been so successful, I never thought it would reach schools and libraries, but these things are under attack too, and so what comes in its place is a fractured, poorly educated, conspiratorial world, and Shane belongs to it. As a fiction writer, I knew I was writing toward that point as I explored each point of view and I wondered what I would find when I got there. As with all characters, you just do your best to understand what could be motivating them. And I think, in a weird way, the same thing that motivates Rhys is motivating Shane, and that’s a fear and a disgust with the state of the world and how wild that the people that we feel the most distanced from, in some ways, are motivated by some of the same emotions, if none of the same information, none of the same empirical reality.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Jess Walters by Rajah Bose.