Making Meaning: Why Symbolic Interpretation Matters in Art and Literature

Among my favorite works exhibited in the Scaife Galleries of my hometown Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art is a beguiling, enigmatic, and beautiful 1956 painting by René Magritte entitled Le Coeur du Monde—“The Heart of the World.”

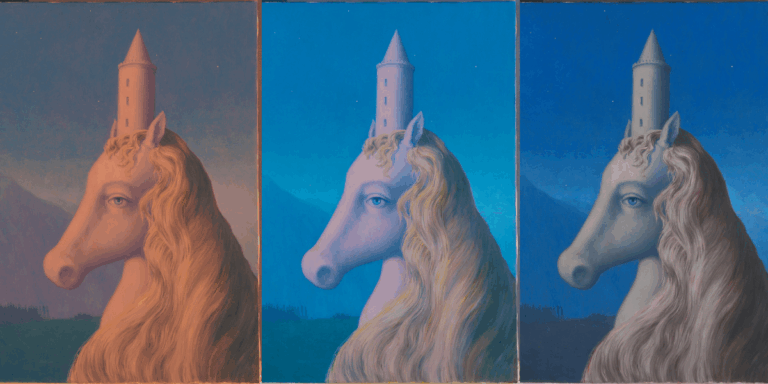

Completed after Magritte had already established his international reputation as among the most influential and important of Surrealists (being less eerie that de Chirico or kitschy than Dali), The Heart of the World is a portrait of distinctly feminine unicorn with cascading blonde hair framed by a fantastical tree-covered mountainous landscape rendered in hues of indigo and cobalt, a glimmering blue eye in profile beneath her horn, which in this piece is a peaked, fairy-tale tower from a castle. A few stars rise above in the late dusk over the unicorn’s valley.

While The Heart of the World may lack the iconic necessity of the Carnegie’s more famous pieces, of Monet’s Water Lillies or Van Gogh’s Wheat Fields After the Rain, it more than makes up for it in sheer evocation, in the absolute sense of mystery it exudes because what could all of it symbolize?

When symbolic interpretation isn’t ignored in literary studies, it’s normally outright dismissed, an idea for cranks and simpletons, children and oddballs.

Like so much of this sterling collection, the Magritte isn’t regularly displayed (Henri Matisse’s The Thousand and One Nights is even squirreled away!), but while I still vainly search for it in the white-walled, minimalist, and modern halls of the Scaife Galleries, it’s still easy to recall the disquieting feeling that accompanies looking into that blue eye even while she is missing today. Impossible not to ask oneself exactly what Magritte intended by the painting, what the unicorn and her castle (such overdetermined images) might mean?

Magritte is an artist who comes with a host of associated personal symbols—all those apples, bowler hats, mirrors, and trains—which interact according to the dictates of dream logic. A Freudian examining the Magritte might focus on that phallic castle, while a Jungian could remind us that archetypically unicorns are representative of chastity.

But The Heart of the World isn’t quite so easily interpretable. As Juan Eduardo Cirlot notes in his delightful classic cult compendium A Dictionary of Symbols, the unicorn has “ambivalent implications.” According to the placard at the museum, I wasn’t the only person struck by the painting, for it claimed that upon the unveiling of the piece at the 1956 Carnegie International a local religious cult formed around the veneration of the piece (strangely no other details were offered). Maybe they too were trying to figure out what the painting was about?

Concerning the symbolic, there is often a whiff of mystery and obfuscation, of being vaguely jangly, a bit mystical and slightly magical. A manner of thinking and analysis that can feel a bit archaic, perhaps even embarrassing. When symbolic interpretation isn’t ignored in literary studies, it’s normally outright dismissed, an idea for cranks and simpletons, children and oddballs. Novelist Saul Bellow in a 1959 New York Times editorial mocked how for some readers a “travel folder signified Death. Coal holes represent the Underworld. Soda crackers are the host. Three bottles of beer are—it’s obvious.” Lacking the utility of “narrative” or “trope,” the rigor of “metaphor” and “metonymy,” the sexiness of “binary opposition” and “deconstruction,” the symbolic feels like a relic of a more primitive era of literary study.

When we do think about the concept we translate it into the more anemic “sign,” making symbology the eccentric sibling of staid semiotics. The symbolic is the embarrassing, dotty grand-aunt of literary theory, maybe appropriate at one time for an academic oddity like Northrop Frye who could unabashedly claim in his 1971 The Critical Path: An Essay on the Social Context of Literary Criticism that “symbols are images of things common to all men,” but today (and for good reason) that can read as naïve, parochial, totalizing, and elitist.

Examining literature or art for symbolism endows works with meanings beyond their capabilities, it recalls the lesson plan of a high school teacher imploring his charges to find easily understandable images of light and dark in Macbeth (though I always appreciated the pedagogical import of my friend who asked each of his students to find all the instances of a penis encoded into the phallically endowed Seamus Heaney poem “Digging”). Such means of interpretation, according to a killjoy like Bellow, reduces the complexity, interiority, and negative capability of literature into the work of a cryptologist trying to crack a code, of an occultist parsing scripture for hidden meanings.

To modernize the adage, if you want to convey a message don’t write a poem or a novel, but send a text. Readers with enthusiasm for the symbolic, Bellow writes, are “apt to lose… [their] head,” falling “wildly in any particle of philosophy or religion” and removing themselves from basic sense. Better to find a means of interpreting literature that doesn’t recall the methods of Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code.

A unicorn is always more than a unicorn (and more than chastity, purity, and virginity as well).

Yet dicks in “Digging” aside, something profound is lost when we reject the symbolic, that well-spring of human communication since an Australopithecus some three-million years ago found a pebble on the South African savannah and held onto it because the rock happened to look like a human face, the beginning of our species’ propensity to see one thing as representing another thing, a grander thing.

A thinking in imagery based in the axiom of the Neo-Platonist Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite who in the fifth-century explained how “What is below is like what is above; what is above is like what is below,” the symbolic a medium of correspondences between the ineffable and the concrete, that ancient Hermetic principle of “What is within is also without.” Understanding symbolic interpretation as merely code-breaking is a popular fallacy, but the correspondences that underlay symbology are never one-to-one, but rather a complex, interlocking system of connotations and often contradictions across time periods and cultures. A unicorn is always more than a unicorn (and more than chastity, purity, and virginity as well).

Cirlot, a Spanish author appropriately associated with Magritte’s Surrealists, argues in A Dictionary of Symbols (published a year before Bellow’s denunciation of that subject) that the “symbol proper is a dynamic… reality, imbued with emotive and conceptual values: in other words with true life.” To read symbolically isn’t to treat literature like a cipher, or even a puzzle, but rather as a cultural wonder cabinet, an archive where allusion and connotations touch the eternal, where any given work is in conversation with a multiplicity which precedes it.

With the completism of a Casaubon, Cirlot references expected symbols such as wheels, crosses, and serpents (the last, among other things is “symbolic of energy itself… hence its ambivalence and multivalences”), as well as more unconventional selections across its 553-pages including the septenary (arrangements of seven), the cromlech (a kind of giant circle), and the Omphalos (Greek for navel, a sign of connection between the heavens and earth). The author writes that “as far as symbolism is concerned, other phenomena of a spiritual kind play an important part,” which is clear in Cirlot’s dictionary (recently republished in the New York Review of Books Classics imprint) a work that calls upon Astrology and Gnosticism, Alchemy and Kabbalah.

Which for many academic readers of literature seems a fine place to keep symbols, an embarrassing remnant of archaic writing and reading, where it’s understood that Plato can represent the soul as a winged chariot drawn by two horses or John Bunyan’s 1678 Pilgrim’s Progress can envision a character named “Christian” (so obvious) on his journey from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City, but where more discerning modern readers have less need of simple parables. In modernity, with a few major exceptions, there is not unreasonably a kind of naivety ascribed to these previous narrative methods, of what Cirlot calls “cheap allegory and mere names.”

Compare the didactic and juvenile clarity of George Orwell’s beast fable Animal Farm, with the pigs Snowball and Napoleon being clear stand-ins for Trotsky and Stalin, to complex works like James Joyces’s Ulysses or Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway and realize that the reason why middle schools assign the first of these and not the last two is because the symbols in that slender novella are easy to understand. Allegory is simply when symbols are made obvious.

Yet as Cirlot emphasizes again and again, the strange symbols which make up his key to all mythologies from the labyrinths to the Mandala, Tarot to the zodiac, are fascinating because they’re ever-shifting, ambiguous, mysterious, and dream-like, not easy to fully interpret as if they were figures in a Thomas Nast political cartoon.

Furthermore, our very lives can be mediated in this realm of images, for as the philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote in The Poetics of Space, a “poetic daydream, which creates symbols, confers upon our intimate moments an activity” that elevates the prosaic into the transcendent. To live symbolically, as it is to read symbolically, is to exist in a network that goes backwards in time and forward to innumerable works yet to written. A symbol, in the truest and most expansive sense of that word, is electric because it gestures towards the possibility of significant meaning, rather than offering any simple definitions. Symbols suggest a world endowed with meaning, but they don’t give up their secrets, and the answers they do give can change depending on who asks them or when.

What’s important is not what these images mean (at least not entirely), but that their existence maintains a belief in meaning. Symbols may be silent, but they’re not agnostic.

Whenever I look for The Heart of the World at the Scaife, I wonder about that supposed religious cult dedicated to the contemplation of the Magritte. Incidentally, I’m not making that detail up, the placard really did report that strange claim, and even after I followed up with the publicists at the Carnegie for an essay about the painting that never got written, I’ve never uncovered any more details about the reality of such a group, a claim as mysterious as the inscrutable symbolism of the painting itself. Perhaps that’s an allegory itself? For that beautiful single-horned beast, replete in works as varied as the King James Bible (where she appears as a mistranslation of the Hebrew for ox), in Lewis Carroll, C.S. Lewis, and Madeleine L’Engle, this unicorn whose “cry is like the sound of bells,” as Cirlot writes.

A mainstay of Medieval art where the animal symbolizes chastity, innocence, purity, and Christ himself, as in the celebrated fifteenth-century tapestries exhibited at the Cloisters. Yet like all powerful symbols, those elements of supposed universal thought, the unicorn never just means one thing.

To poet Rainer Marie Rilke in 1907, the unicorn’s “eyes looked far beyond… reflecting vistas and events long vanished” while for Audre Lorde in 1978 the “black unicorn is restless/the black unicorn is unrelenting/the black unicorn is not/free.” For Rilke the unicorn represents a tradition to be valorized and for Lorde one to be subverted, but in both examples their poems derive their charged power from the image itself, which depends on the creature’s symbolic import across history and culture. “The black unicorn was mistaken/for a shadow or a symbol,” writes Lorde, but the most crucial of symbols are such precisely because they are shadows, the question forever being what casts them?

So much depends on Williams’s red wheelbarrow, Fitzgerald’s green light at the end of the pier, Melville’s mighty white whale, Kafka’s monstrous vermin, but what exactly? The greatest “symbols” dwell between the abstract and the concrete, sense and emptiness; images as much as they are metaphors, where the referent recedes before us, eluding us, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. Moby-Dick, that sleek and deadly cetacean, has been variously proffered as being God, the Devil, America, or nothingness; perhaps he’s all four, or none of them, depending on the situation.

These symbols indicate meaning but keep it shrouded within a kind of semantic Holy of Holies. To pursue such meaning is to frighten it off, like the impure approaching a unicorn, in the same way that repeating a word over and over again drains it of coherence. What’s important is not what these images mean (at least not entirely), but that their existence maintains a belief in meaning. Symbols may be silent, but they’re not agnostic.

Mircea Eliade argues in Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism that the true import of his subject is that “symbolic thought opens the door on to an immediate reality for us… seen in this light the universe is no longer sealed off, nothing is isolated inside its own existence: everything is linked by a system of correspondences and assimilations.” In the algorithmic twilight of meaning, when artificial intelligence robotically inserts images in writing by template and intentionality is absent, the symbolic is a means of reminding us of how all of our words were first spoken by other thinking, believing, and reverential human beings, all the way back to that Australopithecus and his rock, whether we can understand them or not.

When Dante imagined his approach towards God at the conclusion of The Divine Comedy, the Lord appeared as that consummate symbol of the circle, whereby all of us are pages “bound by love into a single volume,” everything in existence nothing less and nothing more than a transcendent symbol for itself, the very enchantments of reality. Understood in that way, the symbolic is nothing less than the interplay of variable meaning, of the negotiations that happen between readers and what they read so as to grasp at the ineffable, even as that wheel forever turns, obscuring a part of the whole just as clearly as it reveals another.