Nobody Knows Why the Caribou Are Disappearing

From this spot on the barren lands, Caribou trails run off like railways over the emerald hills. The paths are innumerable, deep and straight, suggesting mass transit and common purpose—timetables, maps, an orderly procession toward expected ends. That is how it used to be, in the old days.

Hiking over the trails, it sometimes happens that you appear to step into the center of them, as though you’re standing on the hub of a great wheel, gazing out over the spokes. In those moments it feels like you could pick any of the trails and walk it to the horizon. Maybe all the way north to the coastline, or back to the tree line, or even to the city of Yellowknife, 250 miles southwest. Looking out from the hub, you can see there is no place the caribou haven’t been, no direction they haven’t gone. The land isn’t barren, it’s busy with memories of caribou.

On a cool later summer day I choose a trail and follow, clumsily, slotting one boot in front of the other. Beside me, Roy Judas does the same. The animals’ four-legged gait is narrower than ours, so we stumble. Even in huge herds they managed neat marches. I try to imagine the volume of animals required to shape the land this way, to impress their passage so firmly. Tens of thousands. Hundreds of thousands. Decades of migrations, the earth thrumming under their hooves.

Looking out from the hub, you can see there is no place the caribou haven’t been, no direction they haven’t gone. The land isn’t barren, it’s busy with memories of caribou.

“Used to be a highway for them,” Roy says. “All gone now.”

Roy is stout and athletic. He chews a stick, balances a Winchester lever-action across the beam of his shoulders. Today he is angry. Or, no, that’s not quite right. I’m not sure there is a word for what Roy is. We’ve been looking for his caribou for days here in the far east of Canada’s Northwest Territories, and we’ve seen only a handful. By his caribou I mean his people’s, the Tłıc̨ hǫ, or Dogrib, a First Nation of the Dene. The caribou we seek belong to a herd called Bathurst, and there are so few left that even with the help of satellites and tracking collars and seasoned hunters like Roy, they have slipped away along these trails almost every time.

I thought it would be easier to find them. Caribou are big animals; adults weigh a few hundred pounds apiece. Once, not too long ago, there were half a million Bathurst caribou, and in certain places, during certain seasons, you could sit still and watch them stream past in a grand procession that might take days, or weeks. Now only about six thousand animals remain in the herd. That’s still more Bathurst caribou than there are Tłıc̨ hǫ citizens, but in our time the landscape seems to swallow them. Almost as though it were reclaiming them, taking them back. This is one of Roy’s fears. His herd is 98 percent gone. Perhaps the word for what he’s feeling isn’t anger, it’s despair.

We trundle on, shunting tracks. Mosquitoes drone, Roy hums. He cusses. He buzzes. Keep moving, keep looking. He is not so much a restless man as one who, out here, is opposed to stillness. Stillness is sloth and sloth is laziness and laziness is losing the herd. Roy hates losing what he loves.

*

The Tłı̨chǫ live at the edge of the greatest wildlife mystery in North America. All across the top of the continent, caribou herds are declining, from Quebec in eastern Canada to the west coast of Alaska and beyond, into Russia. Those most affected are migratory tundra caribou, the great movers of the north. Annually they walk enormous loops between their winter feeding grounds, usually in or along the boreal forest, and their spring calving grounds on the Arctic tundra. Some herds—tracked by satellites—have been shown to travel farther than any other terrestrial mammal, nearly eight hundred miles in a year.

Migratory tundra caribou can be called many things across the vast spaces they inhabit: In Canada they are barren-ground caribou or eastern migratory caribou, while in Alaska “caribou” alone will usually do. In Russia and Norway, nearly identical animals are called wild reindeer. To the Inuit they are tuktu; to the Inupiat, tuttu. The Tłıc̨hǫ call them ekwo ̨. Whatever their name, the species seems to be vanishing right before our eyes.

After an increase in numbers in the 1990s and early 2000s, caribou declined across their range by 65 percent, from about five-and-a-half million to less than two million. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in its 2024 Arctic Report Card, shows that of about thirteen major herds in Canada, Alaska, and Russia, most have suffered steady losses. The Bathurst have fallen farthest. Several scientists lamented to me that we may watch them go extinct—as a herd, as a body of animals with a shared history, a shared memory, perhaps even a shared culture—within the next few years.

Scientists discussing the Bathurst are often quick to point out that losing a herd isn’t necessarily unusual. They aren’t permanent fixtures of the landscape. Herds routinely grow, shrink, atomize. Sometimes they blink out. This is not a very satisfying assessment for the Tłıc̨hǫ, however, who have been in relationship with the Bathurst for hundreds or thousands of years. For them the questions are not rooted in biology or ecology but existence: If such a fate could overtake a beloved companion, the more-than-human beings, what might become of the people who depend on them?

Early one August I traveled with a small group of Tłıc̨hǫ citizens to the barren lands of the Northwest Territories, to the eastern border of their land. We went by floatplane from Yellowknife; there were no roads where we were headed. To stare out the window at the landscape below was to watch the last of the boreal forest fade and then seem to vanish underwater. Here rose swamps and ponds, enormous dark lakes and silver rivers that branched and ran like strands of mycelium. In all this wet stood islands and carpets of green low brush and mounds of glacial soil, though even these seemed inundated, and at times it was impossible for me to know where liquid ended and solid ground began. Across this space we would search for Bathurst caribou, working as part of a Tłıc̨hǫ government monitoring program.

Our camp sat on a small peninsula that knuckled up from the southeastern shore of a seventy-mile-long lake that on maps is called Contwoyto, though this is not a Tłıc̨hǫ word. They call it Koketi. At the far end of camp stood an outhouse and in the center was the solitary cabin where we cooked and ate meals. Along the perimeter were our tents, in a haphazard row, each one covered with blue tarp to keep out the fierce rain that sometimes seemed not to fall so much as blast horizontally across the face of the earth. At the shore there was a short dock, a white motorboat rocking beside it. On a pole flew the wind-torn flag of the Tłıc̨hǫ Nation, which gave you to know how they see themselves: four tipis made of caribou skin set against a dark blue field.

Most of the camp was enclosed with an electrified fence, to keep out the Big Men, the massive, shuddering ursids that could not be named (more on that later). Some mornings we find their huge footprints in the sand beside the dock, which means they visited us while we slept, when we were most vulnerable, and then they walked away.

If such a fate could overtake a beloved companion, the more-than-human beings, what might become of the people who depend on them?

On our first evening at camp, a woman named Janet Rabesca suggests I make an offering. It’s about nine o’clock and the sky is still bright. She stands outside the little cabin, smoking. Inside, Roy is frying up trout just pulled from the lake. He has battered their bright orange flesh in flour, hoisin sauce, and ginger ale and the sweet scent runs out through the open door and stirs into Janet’s smoke.

“You can give anything,” she says. “Some grass, some flowers.”

She tells me there’s a pouch of tobacco kept here just for this purpose. The point is not the object but the intent. To give before we take, for we are all always taking. I feel a little ashamed for not knowing what to do, but she is not interested in that. She pats me on the shoulder. Come on.

We walk down to the lakeshore, passing through the electric fence. Janet carries some leaves of Labrador tea, gots’agoo lidi, a fragrant plant found here and all over the Arctic, used sometimes to make a fragrant hot beverage. I palm some tobacco. Silently we sift our plants into the water. It is so clear the leaves seem to glide over an invisible plane, casting tiny shadows on the sand below.

Back at the cabin Janet says, “All the shamans, the people who understood this stuff, are gone.” A spray of freckles on her face, strands of gray in her dark hair. “We didn’t have a chance to learn from them. There might be some left, but they keep themselves secret.”

She hopes that’s true, that shamans are out there, holding on to what everyone else has forgotten. There is very little medicine left in the world, she says. Or at least not many people who know how to use it. She is speaking of Indigenous medicine, that which is both medicinal and magical, gifts of the earth for healing and protection and learning.

“Climate change and everything else,” Janet says. “People are sick, the land is sick.”

All these symptoms and nothing for the cause.

__________________________________

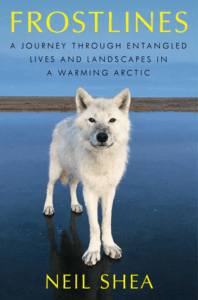

From Frostlines: A Journey Through Entangled Lives and Landscapes in a Warming Arctic by Neil Shea. Copyright © 2025 by Neil Shea. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.