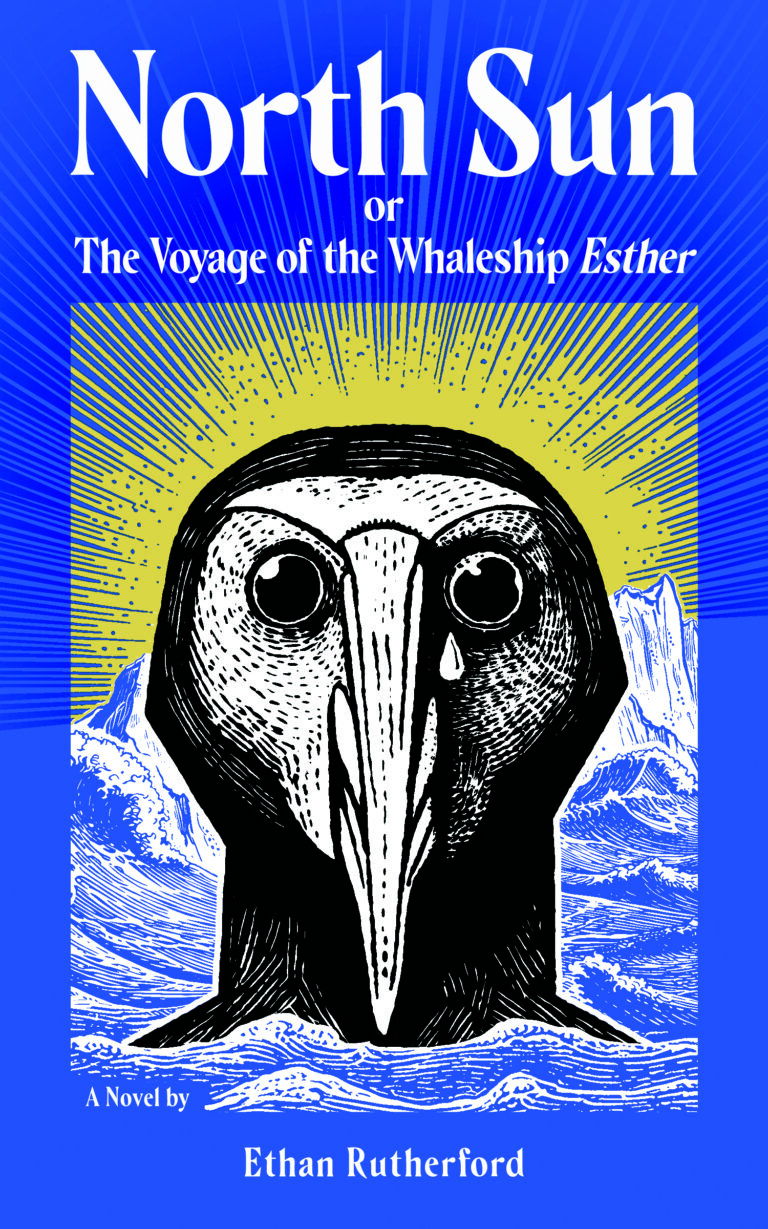

North Sun: Or, the Voyage of the Whaleship Esther

The letter he carries is dated March 1878 and brings the news that there is nothing to be done: the whaleship Dromo has been crushed by the ice in the Chukchi Sea. Her half-full cargo had been unloaded and stored ashore; her masts chopped; her iron instruments used for trading. Her ship’s log remains with her captain, Benjamin Leander, who himself has stayed north. This letter informs the Dromo’s owners of the loss and of Leander’s intention to stay where he is and never return.

These are dim days for the leviathan merchants. The smart whaling families have diversified and will hang onto their wealth for years to come. They’ve bought property in New York, invested in Pennsylvanian land to cash in on petroleum extraction, or else turned to banking.

The less smart, those convulsed by the strange desire to continue doing what had always been done, who consider it a divinely issued directive to rid the waves of great fish, now face a problem: the Atlantic whale that built their houses and ships has seemingly wised up, and anyone wishing to head out to sea to make a living looks at an Arctic voyage of three or five or sometimes seven years before the mast.

Such owners are the Ashleys.

The Dromo had been their ship.

He, himself, has just returned from captaining a three-year expedition during which they’d taken and rendered less than a quarter of the anticipated fish.

How could it be? Only six years earlier, he’d stood at the helm of the Sophie and watched the Japanese waters roil and foam. They’d hunted and rendered so many; the sea was alive with families of whales. They’d turned the bay red and still found more to kill. This time, they’d hauled nearly nothing. His crew was surly and incompetent; they’d knocked into ice cakes and almost stove their own ship. Once north, they’d been so beset by an unrelenting fog that searching for bowhead had been a dreadful exercise. There were no whales anywhere that he, nor anyone else, could see. Other ships found them, but he did not.

To a man they were cold and wet and miserable. Upon landing in New Bedford, his crew took to the docks like scrambling rats, for with the short lay and what they’d slopped over the course of the Sophie’s voyage, and for all their hard work and time aboard, they found they owed money to the outfit. This failure felt terrible. The ice had joined Arnold Lovejoy in dreams and trailed him all the way home.

*

Rounding a last corner, now a wide street. Setting foot on this lane is like opening the doors to a quiet shop where one has no business. The homes are Victorian. The hedges trimmed and boxed.

These grand and sturdy houses face the wharves and look like stern faces themselves. From the third-floor windows, which are the face’s eyes, successful shipowners may sit and survey their fortune being built right in front of them. For years they’ve watched from this high perch, satisfied, as barrels and barrels of oil are rolled from each returning vessel and set on the wharves, or warmed their hands as their ships were heaved over and recaulked and sheathed and prepared for yet another voyage. At least, that’s how it had been.

At a house unlike the others, Arnold Lovejoy stops to adjust his shirt. He checks the address on the letter. He knocks.

He is received at the door by a stout woman in a black woolen overcoat, who, without a word, leads him through a dark and gloomy foyer and sits him in the library. In this room, all the shades are drawn. The walls are decorated with paintings of ships and scenes of the chase. Flensing Among Floes; Spouting Off Larboard; The Cutting Party. In one particularly gruesome illustration, two men prick at a large walrus with cutting spades while a third hoists what appears to be a large golden egg above his head. He looks more closely. It isn’t an egg, exactly.

The walrus wears an expression of deep discomfort.

Directly above the fireplace, centered over the mantle, hangs a portrait of a young boy in a lime-green hunting coat. In one hand he holds a bugle. In the other, a small dog whose mashed face seems drawn out of proportion. The books on the shelves are histories of the Ashley family.

“Your frown,” says Arnold Lovejoy, to the woman who has come and gone with his letter and now sits silently across from him, “is like a symbol in some long-lost alphabet.”

She makes no reply. At the sound of a bell, she turns and walks out of the room, summoning him; he stands and follows. There are no rugs on the floor, nor any wall decoration, but he knows the woman’s coat is made of the finest wool and the wooden floor planks are pine.

A flensing pole leans comfortably in the corner of the staircase.

The curtains in this wide sitting room are drawn as well, and on one table someone has spread a map. The whole place is candlelit; even the dark corners are cast in a fine light. In front of Arnold Lovejoy sits a small man with no hair and a woman with sharp teeth. Ashley himself, and to his left, his wife. “Captain Lovejoy,” says Ashley. “Thank you for delivering your letter. Or, I should say, my letter. The Dromo was my favorite ship. I’m sorry she’s been lost.”

“Very sorry,” says Mrs. Ashley.

They are not really monsters, Arnold Lovejoy knows. They just appear that way. It’s in their blood.

__________________________________

From North Sun by Ethan Rutherford. Used with permission of the publisher, Deep Vellum Publishing. Copyright © 2025 by Ethan Rutherford.