Omar El Akkad on How the Empire Weaponizes Language to Numb Itself to Genocide

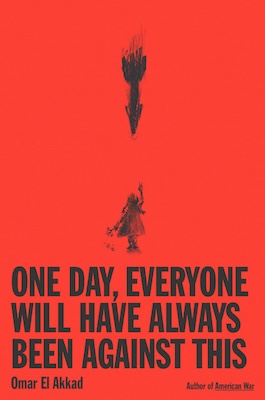

Omar El Akkad’s nonfiction debut, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, is a timely account of a severance from the West and its systems that have long betrayed espoused values.

“The dead dig wells in the living,” El Akkad writes at the end of the prologue, foreshadowing the narrative to come—of contending with the harrowing reality where the Palestinian death toll rises, their pogrom live streamed but impacting only those with a conscience. In the aftermath of a dissonance between reality and the Empire’s narrative—one where Western powers denounce the existence of a genocide, refusing to put an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestine—El Akkad writes about no longer being disillusioned by the facade of Western liberal values and instead, understanding, finally: “Rules, conventions, morals, reality itself: all exist so long as their existence is convenient to the preservation of power.”

El Akkad, who worked as a journalist covering the War on Terror, details those early years when he began to notice the cracks in this “free world”, started to understand how power hinges on the subjugation of another, how language and fear are tools the West maneuvers to its advantage. He recounts his adolescent years in Qatar, when he believed in the West’s promise of freedom, and his teenage years assimilating in Canada. Through a narrative, personal and political, he speaks to the ways Western hypocrisy has revealed itself over the years, culminating at this point—where many, especially those in power, reject the very reality of Palestinians suffering mass slaughter. In the face of this, El Akkad turns to writing—which, he tells me, is his first avenue of retreat—and he speaks of what many of us have been feeling: a rupture in trust in Western institutions that can never again be sutured.

Egyptian-Canadian journalist, Omar El Akkad is the author of American War (named by the BBC as one of 100 novels that shaped our world) and What Strange Paradise (2021 Giller Prize winner). On a Monday afternoon, Omar and I spoke about language as a weapon of oppression, the power of negation, what it means to be a writer in these polarizing times, and more.

Bareerah Ghani: You write,“The empire…is cocooned inside its own fortress of language.” Later on, the book circles this idea of language being usurped from Palestinians. We’ve seen headlines like the Wall Street Journal’s,”Is It Time to Retire the Term ‘Genocide,’” and you bring up countless others, deconstructing them in this book. I’m interested in your thoughts on language as narrative, why it often lies at the center of oppression, and in this case, the erasure of an entire people.

Omar El Akkad: My suspicion is that it has to do with a reluctance on the part of someone with the privilege of looking away, to have to do the work of describing something bloody, grotesque. Throughout my career as a journalist I saw this in various forms, things like collateral damage instead of, we bombed a wedding party. Or prisoners in Guantanamo Bay who aren’t actually prisoners. They’re detainees, which you see mirrored in Israel. It’s not hostages. It’s administrative detention. Hostages are what the barbarians take. The civilized world puts people in indefinite detention.

Hostages are what the barbarians take. The civilized world puts people in indefinite detention.

My suspicion is that it’s an expression of power that you can do this, that you can get away with this but also I think it’s invariably tied with power over chronology, which is to say, that history is reset every time the less privileged party does something horrible. Such that the more privileged party is constantly reacting. Saeed Teebi said this in a panel we were on once—he was talking about the narrative framing of the occupation of Palestine: constantly the evil Palestinian does, and so the civilized Israeli is forced to respond. In that narrative framework, language is doing very, very heavy lifting. Otherwise the overt violence of physical warfare becomes too much for even the numbed sensibilities of somebody living in the heart of the Empire to fully bear. And you see this historically—the Vietnam war, for example, when Americans really started to turn on that, you start to see the visceral imagery of what warfare looks like, of what this campaign of mass destruction is doing. I think here the situation would be similar—if you presented plainly, both in imagery and in language, the reality of not just what is happening in Gaza, but what is happening in the West Bank, and what has been happening to Palestinians for the better part of three quarters of a century, even the most well versed in looking away would have trouble digesting it. But under the guise of language that describes an entire population as being a terrorist entity, for example, or uses passive language to describe a bullet colliding with a 4-year-old young lady—I could not for the life of me tell you what a 4-year-old young lady is—you can cocoon it, and you can soften it, and you can bubble wrap it. So I suspect that that’s what’s at play here, and that if you were to rip it away, the other layers of violence wouldn’t be able to stand on their own.

BG: But we’re also living in unprecedented times where there’s a genocide being live streamed. Yet, people are looking away. What do you make of that?

OEA: I think it’s a muscle that’s been well honed as part of the social contract when living in the most powerful society. There is no shortage of horror that the people in this country I live in and in many of the countries in the West, generally speaking, have been conditioned to look away from. We had twenty years of the so-called War on Terror, leaving millions dead, and by and large this society, through its media apparatus, through its centers of power, was able to look away. And it’s impossible to believe that, once that muscle is so well developed, it can’t be used for virtually anything. I think one of the reasons that you’ve seen it sort of stretched to a breaking point right now is because, like you said, it is being live streamed. The immediacy of it, the horrible intimacy of it is unlike anything I’ve witnessed in my lifetime. Unless you are a complete and total sociopath, seeing that every day has to change something in you.

This is a vast overgeneralization, I apologize, but I think there’s an arc of proximity between a privileged people and the conflicts being waged on their behalf, that runs all the way from written depictions of wartime atrocity, pictures, photographs, and then you get into the Vietnam era and you start to see a film and color film, and you’re getting closer, and it’s becoming more difficult to look away. And then you get into the ’90s and it almost inverts. I remember growing up as a child, I was in Qatar, and we were watching footage of the bombing of Iraq during the First Gulf War, and it’s this grainy green night vision thing. Suddenly, that distance is starting to expand again. And then you get into the War on Terror, and you get this drone footage that looks like something out of a video game. It’s gray scale, very abstract. And now, suddenly, you’re sort of thrown back in. I think that makes it very difficult to look away with as much ease.

BG: You call out the Democratic Party’s hypocrisy, talk about how it’s been their tactic, to play on everyone’s fear of how much worse the alternative would be. But now that Trump has been elected, it’s clear that endorsing mass murder has had repercussions which were maybe, previously, unimaginable for the Democratic Party. Do you think this is the beginning of some change, now that many have abandoned the us versus them mentality?

OEA: The short answer is, Yes. I certainly hope so. This is the first time I’ve seen real domestic political consequences for one of the two central parties in this country, related to Palestine. Previously, you could say or do anything related to Palestinians, and suffer no domestic consequences. And now you watch a Democratic candidate lose to one of the worst human beings ever to run for President, and it’s very difficult not to imagine that voter fury over the carnage in Gaza didn’t play a part in that. So that for me, is a sign.

Under the guise of language that describes an entire population as being a terrorist entity, you can cocoon it, and you can soften it, and you can bubble wrap it.

Another sign is what I see at the ground level political discourse in this country. I’m not talking about the Presidency or Congress or the Senate. I’m talking about City Council elections down the road from where I live in Portland, Oregon, where you start to see council members elected from the working families party, for example. At a very grassroots level, you’re starting to see people just desperate for some other option. A lot of times when you pick up the ballot book here, it’s sort of Republican, Democrat, a bunch of people who are deranged and are going to get about three votes each. And that’s been just sort of what you’re expected to live with. You get two choices, essentially and I’m complicit in this. Up until a year and a half ago I would pick up that ballot, see whoever has the R next to their name, and I would vote for the person with the D. There’s a certain moral threshold that has been crossed where a lot of people, myself included, can no longer do that. So you have the very early makings of—at least at a local level—some kind of alternative. Those two factors are starting to give me some hope for change. The issue, of course, is how many people need to die, and how much carnage needs to be unleashed before we get to that place.

BG: I want to talk about the title, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This. You reference historical evidence of other atrocities committed such as against the indigenous population and then in hindsight, there was an apology. But like we said, this is the first time it’s being live streamed and yet people are looking away. And while you say that yes, you think this is the beginning of change, I wonder if witnessing this kind of blatant dissonance fractures your belief in this imagined future where everyone says, – even if for self-interest – yes, it was terrible what happened to Palestinians.

OEA: The title of the book comes from this tweet. The original title was The Glass Coffin, and it was only after completion that one of the editors at my publishing house suggested using the current title. I only say this because I’m trying to convince people that I didn’t just take a tweet and sort of stretch it out into 200 pages. I promise that’s not what happened. But one of the two things I found from talking to people in these early days of the book is that some folks seem to think that I mean next week, like the one day is coming imminently. But the timeframes I’m looking at are relative to things such as the genocide of the indigenous people in this hemisphere, where we have land acknowledgements today, and the US Government put out a little statement a few years ago, apologizing, hundreds of years after the fact. I hope that it happens in my lifetime but even that would be optimistic. The other thing that some people seem to think is that I consider that day, when it arrives, to be a good day, and in fact, quite the opposite is true. I have quite a bit of pent up preemptive fury about that day, because how many people had to die?

The kind of person I’m thinking of with that title is the kind of person for whom none of this matters. There’s no personal stakes. They can’t point out Israel or Palestine on a map. They simply want to know what the majority of polite society is thinking right now. There is this narrative that sort of appears well after the fact, where the horrible thing is considered this temporary aberration. They didn’t know better back then. Now we know better. It’s never true. It wasn’t true in the case of slavery or segregation or apartheid, and it won’t be true in this situation. It’ll just be an effective and useful narrative parachute.

I have no doubt it’s coming. I just have real trouble wrapping my head around the sheer amount of carnage that happens between now and that moment.

BG: You state at the beginning of this book that this is an account of an ending, a severance from the West, and you speak of negation, this power to turn away, being dangerous and valuable. It got me thinking about well, what does it mean to not participate in the system? Sure we have boycotts. But what about those who are tied to the system, have been all their lives?

All of us as writers have an obligation to bear witness, even if we knew for a fact that it wouldn’t change a single thing.

OEA: I struggle with this. And the way I’ve started thinking about all this—and it’s not particularly novel—is as different arenas of engagement. One of the criticisms of this book that I think is perfectly valid, and against which I have no defense, is that I talk about all this resistance and its importance, and then get real squishy about the idea of armed resistance. But I have no right to tell anybody how to resist their occupation. And I can talk to you about how I’m a pacifist, I abhor all violence, and I do believe that about myself, but by virtue of how my tax money is spent, I’m one of the most violent human beings on earth. And so, as much as I want to make the moral argument for nonviolence, my argument for nonviolence now is purely pragmatic. There’s an asymmetry of power in that particular arena of engagement. The State has the bigger guns, and also narrative justification for any amount of violence. There are other arenas where the asymmetry is not nearly as glaring, or, in fact, inverted. The arena of non-involvement has an entirely different power structure. The State has a much harder time punishing you for what you don’t do or what you don’t buy. The arena of joy is very asymmetrical towards the individual. And you see this every time Israel releases a hostage, and they tell them not to display any expressions of joy when they see their family again. It is a deeply disturbing thing for me that I have to make a pragmatic rather than moral argument for shifting arenas away from violence, for example. But in terms of this non-involvement I wish that there was an algorithmic approach where I do this, this and this in every situation. But it’s been very different for me. There’s been situations where I’ll go give this talk. I’ll take the money. I’ll donate it somewhere good. Or I refuse to give this talk, because this institution has brutalized its own students. Everyone makes these decisions on a case by case basis and according to their own moral thresholds.

BG: You have an entire chapter on your shifting relationship with the publishing industry, and to writing itself. At one point you ask, “What is this work we do? What are we good for?” Now that you’ve written a book that will forever stand witness to the worst of humanity, what is your perception of this work we do– what does it mean to be a writer?

OEA: I’ve said this a couple of times, and it’s not me playing at false humility, I don’t think this is a book that’s going to be remembered. But if it is, I think it’s going to be remembered as one of the tamest examples of its kind. The amount of rage I’ve seen is orders of magnitude worse than what anyone who simply watches the nightly news in the U.S. or Canada would imagine. There’s this immense, almost incandescent rage at what has been allowed to happen, and how hollow so many of the covenants and agreements, and principles of equal justice and international law have proven themselves to be. In that context, I think that all of us as writers have an obligation, first and foremost, to bear witness, even if we knew for a fact that it wouldn’t change a single thing. Beyond that I’m not really sure anymore. And I used to be pretty sure both about the obligations of a writer, or the sort of job description of a writer, for lack of a better phrase, but also for the value—that we are creating this work that is going to outlive us and that this means something. But I don’t know anymore.

I don’t want to make the case that everyone has to drop everything they’re doing and write about this. Where I have really become disillusioned is in watching writers, who have previously traded on the currency of standing in the way of injustice, now suddenly taking a backseat and keeping their head down. And that’s in part because I’ve seen a kind of arc related to how situations like this, particularly grotesque, horrific situations, are treated. For example, the War on Terror, where there were these periods of immense silence, so many artists, so many writers kept their heads down and then you started to see, when it was safe enough, a trickle of stories after the fact, usually from the perspective of some former marine talking about how sad it made them to have to kill all these brown folks, and then their short story collection wins whatever prestigious prize. To know that this arc is likely still available to all of those writers where, 23 years from now, the same people who said nothing, are going to write incredibly moving stories about the mass graves they uncover in Northern Gaza, is infuriating.

BG: What do you make of all this misinformation on mainstream media, and does it diminish the impact of the work you’re doing with this book?

Where I have become disillusioned is in watching writers, who have traded on the currency of standing [up to] injustice, now suddenly keeping their head down.

OEA: I think it’s a numbing agent. I know when I talk to most people on this earth, a certain narrative is in place—one in which the wholesale slaughter of a people is wrong, and occupation and theft of their land is wrong. As much as that narrative may exist and is predicated on what’s actually happening, if you’re living in the heart of the Empire and you’re subscribed to that other narrative where there’s an overriding, inherent goodness to anything your nation state does, to even glance at that other narrative imposes a set of obligations on you that are crushing because now you suddenly have to contend with hundreds of thousands of dead people, dead kids, with 75 plus years of occupation, with the exact same things that are bemoaned and apologized for at every land acknowledgement at every literary festival I’ve ever gone to in this part of the world. It’s a crushing thing to even consider that that narrative might not only exist, but might have a far more direct relationship with reality than whatever the hell you’re watching on the nightly news.

Palestine is going to be free, and beyond that it is going to teach generations of human beings about what freedom actually looks like. And this work is going to be aided by activists around the world but is going to be done, and is being done by Palestinians themselves. I don’t think I’m doing a damn thing. This book for me is an accounting of a kind of leave taking from the person I was for the vast majority of my life into an uncertain space. The fundamental sense from the last year and a half at least personally, more than solidarity and activism, is a sense of complete failure, so it makes it difficult to answer that question about diminishing the impact of it, because it does come from a place of complete impotence. And yet, I have to set aside that feeling and go do whatever work I can. Because right now everything matters, every little piece of work, no matter how dejected I might be.

The post Omar El Akkad on How the Empire Weaponizes Language to Numb Itself to Genocide appeared first on Electric Literature.