On Understanding and Capturing the Horrors of War and Fascism

My grandmother was a teenager when the bombers and fighters flew overhead for Gernika on April 26, 1937, shattering any remaining peace this area of the world would know for the next 80 years.

For three hours, a mob of planes belonging to the German Condor Legion and Italian Aviazione Legionaria blitzed Gernika, the village that is the spiritual center of the Basque Country but that served little military significance during the Spanish Civil War. Instead, the attack was meant to sow the sort of terror Spanish General Emilio Mola had promised the citizenry of the Basque province of Bizkaia if they didn’t immediately surrender. Gernika was at capacity on account of it being market day. Those attempting to flee the incendiary bombs torching the village were either shot down by fighter planes or forced back into the inferno. This birthday present to Hitler would be the first carpet bombing of its kind. The Basque government put the number of those killed in the attack at 1,645, though this figure could easily be higher.

The challenge for me exploring this time in fiction was how to fully realize on the page people stirred by such necrophilous discourse.

My grandmother wasn’t able to see any of this ruin-making from where she stood, only the squadrons brushing past the treetops. Meanwhile, the ceaseless thunder from the explosions—at one point, shells fell for every second in a minute—rolled over the mountain ridge toward her. That night, the whole valley glowed red. It was this detail she recalled most vividly as she told me about the bombing, the fire that lit and veined the clouds crimson.

The British journalist GL Steer was the first English-language reporter to visit the village. The fascist propogandists had beat him to the scene, already giving lumpy shape to the lie that retreating Basques had set fire to the village, despite every credible piece of evidence to the contrary. “The destruction of Gernika was not only a horrible thing to see,” Steer wrote, “it led to some of the most horrible and inconsistent lying heard by Christian ears.”

What I don’t know: when my grandmother watched those German and Italian planes descend onto Gernika, was her father by her side? He was an ardent and vocal devotee of General Francisco Franco. Not common in the Basque Country, though not a rarity either. The area was considered Spain’s most Catholic region, but its people were more dog-headedly devoted to ideas of independence and democracy than any other ideology. When they threw their lot in with the Spanish Republic over Franco and the Spanish clergy, Franco was determined they’d pay with their blood. For the most part, in the words of Steer, “the Basque bound together his little nation in strong bands of human solidarity.” They resisted as well as a people could who lacked anti-aircraft artillery and even much of any military assistance from the government they were defending. But in a free land you’ll find all sorts, including my great-grandfather, who was so severely Catholic he’d named his daughters Teologia, Trinidad, and Natividad, which translates into English as Theology, Trinity, and Nativity. Three of his five sons became priests, and Trinidad served most of her life as a nun.

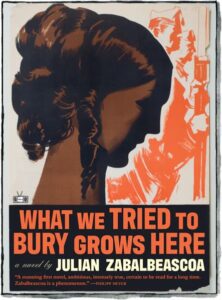

Even after the bombing, throughout the rest of the war and the nightmarish dictatorship, Franco had my great-grandfather’s vocal support. While writing my debut novel What We Tried to Bury Grows Here, which takes place over the course of the Spanish Civil War, I tried to understand this man who could see Gernika razed, his neighbors slaughtered, and either think it necessary for the restoration of a sort of theocracy or was determined to commit himself to the fascist’s narrative. Or, more than likely, some combination of the two.

Such blinding fundamentalism made noxious the air many breathed in 1930’s Spain. Most everyone of consequence standing before a microphone spoke in terrifying absolutes. General Franco told the reporter Jay Allen that no compromise with the enemy was possible and that, if need be, his side would shoot the other half of Spain in order to win.

Among the fractious camps across the political aisle, there were orators like Dolores “La Pasionaria” Ibárruri saying of the opposition, “We must exterminate them! We must put an end once and for all to the threat of a coup d’etat, to military intervention!”

Such a dialogue provoked, in the words of anarchist intellectual Federico Montseny, “a lust for blood inconceivable in honest men before.” As Anthony Beevor wrote in The Battle for Spain, both sides “justified their actions on the grounds that if they did not act first, their opponents would seize power and crush them.” And so the country zealously engaged in collective suicide, propagandists helping make the most inhumane acts permissible.

The challenge for me exploring this time in fiction was how to fully realize on the page people stirred by such necrophilous discourse, imbuing with humanity those determined to strip it from others. And, as was often my case, how to do this for characters I disagreed with politically and morally, for those with whom my great-grandfather might have found common cause. Away from my writing desk (which is our dining table), I can be leprous with political convictions and judgment that borders on contempt. In that regard, I am very much my great-grandfather’s great-grandson. But if my writing has any chance of growing beyond my own limitations, I mustn’t allow any such judgment near the dining table while it’s functioning as my writing desk.

I didn’t put them on the page to castigate, celebrate, or redeem them. They are there because I was curious about them.

What We Tried to Bury Grows Here consists of twenty chapters, each told by a different character as they experience the Spanish Civil War. Through this chorus of voices, we follow Isidro, a young Basque soldier, and Mariana, a writer of leftwing pamphlets and mother of two, as they struggle to keep hold of some grace and mercy in a country determined to tear itself apart. Several of these narrators are fascists, many more have killed. I didn’t put them on the page to castigate, celebrate, or redeem them. They are there because I was curious about them, regardless of the flag waving over their heads. It was a practice the novel taught me to adopt early on.

In the first chapter I wrote (though it appears late in the novel) there was a point where I became uncomfortable with what the narrator, a Nationalist soldier participating reluctantly in the massacre at Badajoz, was showing me. There was too much loss and blood across the page. I was troubled by his cowardice and how it made him complicit in the tragedy being made before him. Authorially, I wrestled the reins from him and started writing toward more palatable territory, transforming him into someone he was not, but with each new lifeless sentence I felt the narrator’s voice fade from me. If there’s any legitimacy to what spiritual mediums do, perhaps they get this feeling. The narrator stopped trusting me. Soon, he was gone. I deleted all that new material and returned to the slaughter in its mad pitch, pledging to my narrator that I would not steer or judge, that I was in service to his voice and his story, not the other way around.

What We Tried to Bury Grows Here attempts, among other things, to understand how fear and confusion can make people susceptible to such messages as those that galvanized so many during the Spanish Civil War and made many more complicit in the destruction it wrought. This requires curiosity, empathy, and compassion. The very instruments missing from the propagandist’s toolbox. The antithesis to what lit Spain’s civil war and comforted my great-grandfather that, at long last, those he disagreed with would be silenced.

__________________________________

What We Tried to Bury Grows Here by Julian Zabalbeascoa is available from Two Dollar Radio.