One Man’s Trash: Reflections on a Failed Novel

I started trash bashing three weeks after it became clear to me that my first novel was not going to sell.

I’d tried to be honest with myself, from the moment the manuscript went out on submission, that the odds of it finding a publisher were slim. After all, I’d stuffed it with just about every first-novel cliché. For starters, it was huge—an epic retelling of The Wizard of Oz set in rural Idaho, told across three perspectives separated by time and space. It had talking marionettes, faceless ghosts, and the sort of multiversal narrative leaps I’d seen employed—with decidedly greater success—by writers like David Mitchell and Helen Oyeyemi. It was a novel about the mythologies families erect to make sense of their complicated pasts.

But it was also about the history of cartography. And the economic and social fallout of decades of extractive mining in the northwest. Oh, and it was about the art of puppeteering, too. Why not? Even after I’d cut the manuscript in half, it still came out to a breezy 148,000 words.

Despite my hunch that the book wouldn’t sell, the publishing world’s rejection still devastated me. After six months of passes from editors, I’d finally come face to face with the fact that a project I’d spent two years writing—and a decade thinking about—would never be read by more than half a dozen people. For years, publishing a novel had been the star around which my life had orbited. I’d spent the better part of my twenties operating under the mistaken belief that my chronic anxiety disorder, which saw me agonizing over every moment I spent away from the page, was actually just proof that I was devoted to my craft. Everything that didn’t directly relate to reading and writing was either a pointless distraction or a brief reward for good behavior.

Like so many artists whose work exists primarily in the mind, I’d harbored a lifelong envy of people who could make things with their hands, and I’d filled my fiction with tinkerers and craftsmen as compensation for my own lack of tactile expertise.

Even worse, though, were the deeper insecurities this defeat seemed to validate. For so long I’d been embarrassed by my propensity for injecting elements of fairytales and science fiction into my work when so many of my peers were trimming their stories down to slim, devastating shards of minimalist prose. The book’s failure seemed like the final proof of what I’d always feared: that there was something unsophisticated, something juvenile, about my inability to sit down and write a simple, serious story. For the rest of the month, I oscillated between moments of dull acceptance and outright despair, haunted by the growing suspicion that I wasn’t actually very good at the thing I’d dedicated my entire life to.

And then I found trash bashing.

Or rather, I found a lot of videos online about trash bashing. At the time, I was working remotely for a Medicaid payroll company, which meant staring at Excel spreadsheets until my eyes burned. One of my only reliefs during that time was trawling YouTube for videos of people showing off their crafting techniques—carving miniature landscapes from foam and wood, or building elaborate machinery from 3D-printed parts—which struck me as a far better use of one’s time than the thankless drudgery of putting words together.

Like so many artists whose work exists primarily in the mind, I’d harbored a lifelong envy of people who could make things with their hands, and I’d filled my fiction with tinkerers and craftsmen as compensation for my own lack of tactile expertise. Nowhere was this truer than in my novel, which was stuffed with clockwork cities and Oz-inspired animatronics, all of which I described in intricate detail, as if writing about these objects in enough depth might satisfy the itch.

It only took a few hours for YouTube’s algorithm to provide me with hundreds of trash bashing tutorials, a Library of Alexandria of profoundly talented weirdos who’d perfected the art of turning trash into hulking robots, flying boats, Wild West dioramas, and all manner of mutants and monsters. Many of these creators got their start in the world of miniature wargaming, where the act of “kitbashing” involves taking parts from different modeling kits to make something new.

Trash bashing takes this a step further, utilizing junk instead of expensive modeling kits. This lends the community an anarchic, egalitarian bent: people swap models and digital files, repurpose one another’s designs, and share their favorite crafting techniques with unguarded enthusiasm. This seemed antipodal to my experience as a writer, where protecting one’s solitary vision against the sullying influence of other authors could still feel like the reigning orthodoxy, even though we all knew that every story was ultimately an amalgamation of everything else we’d read, sifted through for our favorite bits, and recycled and rearranged into interesting new shapes.

In trash bashing, this practice is wonderfully explicit. Many of the videos I watched that day focused exclusively on where to find the best parts. Spray bottles, empty pens, and boxy food containers were excellent for bulking out the “silhouettes” of a model. Old toys could be harvested for arms and legs, while broken electronics were a cornucopia of wires, dials, and paneling. Hardware stores were the best venue for cheap glues, glazes, and epoxies, which could be smeared, stuffed, and sanded into every crack and crevice.

The sense of fulfillment was immediate, and far more pronounced than anything I’d felt for my writing in a long time. I’d made something I could hold.

As I watched these creators spray their models with a coat of black primer, mesmerized by the way paint suddenly transformed the multicolored jumble of junk into a cohesive sculpture, I was reminded of the way that a good story, initially just a messy conglomeration of descriptions, sensations, and dialogue, could suddenly cohere into something meaningful when it finally found its proper composition.

At the end of the day I leaned into my fiancée’s office and announced that I was going to start building things out of trash. “Of course you are,” she said, not even looking up from her computer screen. After a quick trip to the local craft store and an expedition into our recycling bin, I glued some bits of wire and tubing to an old prescription bottle and found myself cradling my very own little robot. The sense of fulfillment was immediate, and far more pronounced than anything I’d felt for my writing in a long time. I’d made something I could hold.

And even better: there was no sense of having to do anything with it. No magazines or editors to appeal to, no sense of having to match up my creation to someone else’s taste. By the end of the week I’d finished my little machine—a cyclopean android hunched beneath the weight of its junky backpack, hiking pole in hand—and felt giddy with satisfaction. I placed the figure atop my bookshelf and stood up every few minutes to admire it.

Over the next year, trash bashing became an integral part of my life. I filled our garage with piles of soap dispensers, recycled takeout containers, and whatever vaguely interesting toys I’d found at garage sales and secondhand stores. I acquired a serviceable collection of saws, knives, calipers, glues, and paintbrushes, and went about the work of hacking all that old plastic into claptrap spaceships and beetle-riding robot cowboys.

In the same way my stories started with a vague shape in my mind, my models began as a blocky outline, the hastily sawed tubes and cubes only hinting at the figure they might become. Then came the detailing—or greebling, as it’s known, a reference to the extraneous sci-fi doodads applied to practical effects in film—where a few carefully applied beads and curled cables become futuristic panels and wiring. Was this any different from how, after I finished stumbling through a story’s first draft, I went about the careful work of teasing out details, tightening language, and uncovering unexpected connections between seemingly disparate plot elements and themes?

I noticed more grandiose parallels, as well. In the same way that writing had taught me to pay attention to life, to perpetually hoover up sensory details and bits of dialogue around me, trash bashing cultivated a new propensity for seeing interesting possibilities in everyday items. It reminded me that one of the fundamental joys of art is the way it opens us up to our own existence, makes us stop and stare curiously at the things we’ve come to think of as banal.

Yet there was freedom to trash bashing, a willingness to lose myself in the creative process, that was distinct from my feelings about writing. I found myself thinking of a quote from Lynda Barry, who I’d always admired for her commitment to art for art’s sake: “You have to be willing to spend time making things for no known reason.”

There might have been a time in my life when this was true of writing, but those days had long passed. What defined my relationship to writing now was a pervasive sense of anxiety. Was I writing enough? Was it any good? If I could just tell a direct, realistic story, without any of that embarrassing strangeness that inevitably wound up in my work, would I finally find success?

To put it as unpoetically as possible: I’d written because it was something to do.

It would be reductive to say that trash bashing taught me to stop agonizing over my writing. But I do think it helped me begin decoupling my stories from my self-worth: to put my desk in the “corner of the room,” as Stephen King puts it in On Writing. To see my writing as something that enriches my life, and not the other way around.

More than that, though, trash bashing reminded me that the elements I’d come to be ashamed of in my work—inspired by decades of decidedly “trashy” comic books, cartoons, and video games—were the very things that had brought me to the page in the first place. I hadn’t been inspired to write by lofty goals of literary fame. I’d been a lonely twelve-year-old uprooted from California to northern Idaho, a pasty recluse who’d responded to his newfound isolation by spending whole days on the web, roleplaying fallen angels and dashing rogues in online anime forums. I’d written, not out of some lofty sense that it was my vocation, but out of boredom and loneliness. To put it as unpoetically as possible: I’d written because it was something to do.

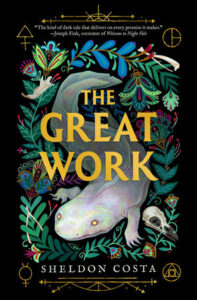

No one bought my first novel. But by the time the final passes rolled in, I was halfway through my next book. It was a story no less strange than the first: a supernatural western about an aspiring alchemist living in the Olympic Peninsula in the 1880s, hellbent on tracking down and killing a giant salamander whose blood he believes will bring his best friend back to life. A grim fable about grief, the devastation of the frontier, and—perhaps most notably—what it means to live beyond the failure of our most precious dreams.

As I went out on submission with The Great Work, I felt an odd sort of ambivalence about whether the book would be published. Obviously I was nervous, but a rejection in my inbox no longer sent me spiraling. I’d done all I could, after all. I wrote the story I wanted to write: a story inspired by the same sorts of weird preoccupations—alchemical symbolism, spaghetti westerns, doomsday cults, giant amphibians—that I’d begun to blame for my first novel’s unpublishability. Whether the market wanted that story was beyond my control. Plus, I was no longer only a writer—I was just someone who liked to make things, in the same way that other people like to garden, or hike, or collect novelty coffee mugs.

This time, I got lucky. The Great Work landed in the hands of an editor who saw some potential in my dark, peculiar story. And here again I found another echo of trash bashing in my writing work: collaborating with a good editor on a novel, it turns out, isn’t all that different from the back-and-forth creative play that comes so naturally to creators in the crafting community. To have your work taken seriously by another person, to see someone else disentangle possibilities in your story that you could never have imagined, to share in their insights and revelations over material that had long become stale to you, turned out to be my favorite part of finally publishing a book.

Success was a joy. But surprise, surprise: it hardly stifled my desire to publish. I’m well into my third novel now, and already those old insecurities are scouting the edges of my mind. But when I find myself sitting at my computer, feeling hopeless, I simply turn around and wheel my chair over to my crafting desk, its surface covered with circuit boards, q-tips, empty spice bottles, and some mangled plastic dinosaurs. I start sifting through all that colorful junk, searching for the best bits to glue together, thankful to have such an interesting way to pass the time.

__________________________________

The Great Work by Sheldon Costa is available from Quirk Books, an imprint of Andrews McMeel Publishing.