Peter Christen Asbjornsen – Round the Yule-Log: Christmas in Norway

The wind was whistling through the old lime and maple trees opposite my windows, the snow was sweeping down the street, and the sky was black as a December sky can possibly be here in Christiania. I was in just as black a mood. It was Christmas Eve,—the first I was to spend away from the cosey fireside of my home. I had lately received my officer’s commission, and had hoped that I should have gladdened my aged parents with my presence during the holidays, and had also hoped that I should be able to show myself in all my glory and splendour to the ladies of our parish. But a fever had brought me to the hospital, which I had left only a week before, and now I found myself in the much-extolled state of convalescence. I had written home for a horse and sledge and my father’s fur coat, but my letter could scarcely reach our valley before the day after Christmas, and the horse could not be in town before New Year’s Eve.

My comrades had all left town, and I knew no family with whom I could make myself at home during the holidays. The two old maids I lodged with were certainly very kind and friendly people, and they had taken great care of me in the commencement of my illness, but the peculiar ways and habits of these ladies were too much of the old school to prove attractive to the fancies of youth. Their thoughts dwelt mostly on the past; and when they, as often might occur, related to me some stories of the town, its people and its customs, these stories reminded me, not only by their contents, but also by the simple, unaffected way in which they were rendered, of a past age.

My comrades had all left town, and I knew no family with whom I could make myself at home during the holidays. The two old maids I lodged with were certainly very kind and friendly people, and they had taken great care of me in the commencement of my illness, but the peculiar ways and habits of these ladies were too much of the old school to prove attractive to the fancies of youth. Their thoughts dwelt mostly on the past; and when they, as often might occur, related to me some stories of the town, its people and its customs, these stories reminded me, not only by their contents, but also by the simple, unaffected way in which they were rendered, of a past age.

The antiquated appearance of these ladies was also in the strictest harmony with the house in which they lived. It was one of those old houses in Custom House Street, with deep windows, long dark passages and staircases, gloomy rooms and garrets, where one could not help thinking of ghosts and brownies; in short, just such a house, and perhaps it was the very one, which Mauritz Hansen has described in his story, “The Old Dame with the Hood.” Their circle of acquaintances was very limited; besides a married sister and her children, no other visitors came there but a couple of tiresome old ladies. The only relief to this kind of life was a pretty niece and some merry little cousins of hers, who always made me tell them fairy tales and stories.

The antiquated appearance of these ladies was also in the strictest harmony with the house in which they lived. It was one of those old houses in Custom House Street, with deep windows, long dark passages and staircases, gloomy rooms and garrets, where one could not help thinking of ghosts and brownies; in short, just such a house, and perhaps it was the very one, which Mauritz Hansen has described in his story, “The Old Dame with the Hood.” Their circle of acquaintances was very limited; besides a married sister and her children, no other visitors came there but a couple of tiresome old ladies. The only relief to this kind of life was a pretty niece and some merry little cousins of hers, who always made me tell them fairy tales and stories.

I tried to divert myself in my loneliness and melancholy mood by looking out at all the people who passed up and down the street in the snow and wind, with blue noses and half-shut eyes. It amused me to see the bustle and the life in the apothecary’s shop across the street. The door was scarcely shut for a moment. Servants and peasants streamed in and out, and commenced to study the labels and directions when they came out in the street. Some appeared to be able to make them out, but sometimes a lengthy study and a dubious shake of the head showed that the solution was too difficult. It was growing dusk. I could not distinguish the countenances any longer, but gazed across at the old building. The apothecary’s house, “The Swan,” as it is still called, stood there, with its dark, reddish-brown walls, its pointed gables and towers, with weather-cocks and latticed windows, as a monument of the architecture of the time of King Christian the Fourth. The Swan looked then, as now, a most respectable and sedate bird, with its gold ring round its neck, its spur-boots, and its wings stretched out as if to fly. I was about to plunge myself into reflection on imprisoned birds when I was disturbed by noise and laughter proceeding from some children in the adjoining room, and by a gentle, old-maidish knock at my door.

On my requesting the visitor to come in, the elder of my landladies, Miss Mette, entered the room with a courtesy in the good old style; she inquired after my health, and invited me, without further ceremony, to come and make myself at home with them for the evening. “It isn’t good for you, dear Lieutenant, to sit thus alone here in the dark,” she added. “Will you not come in to us now at once? Old Mother Skau and my brother’s little girls have come; they will perhaps amuse you a little. You are so fond of the dear children.”

On my requesting the visitor to come in, the elder of my landladies, Miss Mette, entered the room with a courtesy in the good old style; she inquired after my health, and invited me, without further ceremony, to come and make myself at home with them for the evening. “It isn’t good for you, dear Lieutenant, to sit thus alone here in the dark,” she added. “Will you not come in to us now at once? Old Mother Skau and my brother’s little girls have come; they will perhaps amuse you a little. You are so fond of the dear children.”

I accepted the friendly invitation. As I entered the room, the fire from the large square stove, where the logs were burning lustily, threw a red, flickering light through the wide-open door over the room, which was very deep, and furnished in the old style, with high-back, Russia leather chairs, and one of those settees which were intended for farthingales and straight up-and-down positions. The walls were adorned with oil paintings, portraits of stiff ladies with powdered coiffures, of bewigged Oldenborgians, and other redoubtable persons in mail and armour or red coats.

“You must really excuse us, Lieutenant, for not having lighted the candles yet,” said Miss Cicely, the younger sister, who was generally called “Cilly,” and who came towards me and dropped a courtesy, exactly like her sister’s; “but the children do so like to tumble about here before the fire in the dusk of the evening, and Madam Skau does also enjoy a quiet little chat in the chimney corner.”

“You must really excuse us, Lieutenant, for not having lighted the candles yet,” said Miss Cicely, the younger sister, who was generally called “Cilly,” and who came towards me and dropped a courtesy, exactly like her sister’s; “but the children do so like to tumble about here before the fire in the dusk of the evening, and Madam Skau does also enjoy a quiet little chat in the chimney corner.”

“Oh, chat me here and chat me there! there is nothing you like yourself better than a little bit of gossip in the dusk of the evening, Cilly, and then we are to get the blame of it,” answered the old asthmatic lady whom they called Mother Skau.

“Eh! good evening, sir,” she said to me, as she drew herself up to make the best of her own inflated, bulky appearance. “Come and sit down here and tell me how it fares with you; but, by my troth, you are nothing but skin and bones!”

I had to tell her all about my illness, and in return I had to endure a very long and circumstantial account of her rheumatism and her asthmatical ailments, which, fortunately, was interrupted by the noisy arrival of the children from the kitchen, where they had paid a visit to old Stine, a fixture in the house.

“Oh, auntie, do you know what Stine says?” cried a little brown-eyed beauty. “She says I shall go with her into the hay-loft to-night and give the brownie his Christmas porridge. But I won’t go; I am afraid of the brownies!”

“Never mind, my dear, Stine says it only to get rid of you; she dare not go into the hay-loft herself—the foolish old thing—in the dark, for she knows well enough she was frightened once by the brownies herself,” said Miss Mette. “But are you not going to say good evening to the Lieutenant, children?”

“Oh, is that you, Lieutenant? I did not know you. How pale you are! It is such a long time since I saw you!” shouted the children all at once, as they flocked round me.

“Now you must tell us something awfully jolly! It is such a long time since you told us anything. Oh, tell us about Buttercup, dear Mr. Lieutenant, do tell us about Buttercup and Goldentooth!”

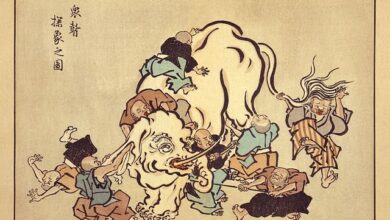

I had to tell them about Buttercup and the dog Goldentooth, but they would not let me off until I gave them a couple of stories into the bargain about the brownies at Vager and at Bure, who stole hay from each other, and who met at last with a load of hay on their backs, and how they fought till they vanished in a cloud of hay-dust. I had also to tell them the story of the brownie at Hesselberg, who teased the house-dog till the farmer came out and threw him over the barn bridge. The children clapped their hands in great joy and laughed heartily.

“It served him right, the naughty brownie!” they shouted, and asked for another story.

“Well,” said I, “I will tell you the story of Peter Gynt and the trolls.

“In the olden days there lived in Kvam a hunter whose name was Peter Gynt, and who was always roaming about in the mountains after bears and elks, for in those days there were more forests on the mountains than there are now, and consequently plenty of wild beasts.

“In the olden days there lived in Kvam a hunter whose name was Peter Gynt, and who was always roaming about in the mountains after bears and elks, for in those days there were more forests on the mountains than there are now, and consequently plenty of wild beasts.

“One day, shortly before Christmas, Peter set out on an expedition. He had heard of a farm on Doorefell which was invaded by such a number of trolls every Christmas Eve that the people on the farm had to move out, and get shelter at some of their neighbours’. He was anxious to go there, for he had a great fancy to come across the trolls, and see if he could not overcome them. He dressed himself in some old ragged clothes, and took a tame white bear which he had with him, as well as an awl, some pitch and twine. When he came to the farm he went in and asked for lodgings.

“‘God help us!’ said the farmer; ‘we can’t give you any lodgings. We have to clear out of the house ourselves soon and look for lodgings, for every Christmas Eve we have the trolls here.’

“‘God help us!’ said the farmer; ‘we can’t give you any lodgings. We have to clear out of the house ourselves soon and look for lodgings, for every Christmas Eve we have the trolls here.’

“But Peter thought he should be able to clear the trolls out,—he had done such a thing before; and then he got leave to stay, and a pig’s skin into the bargain. The bear lay down behind the fireplace, and Peter took out his awl and pitch and twine, and began making a big, big shoe, which it took the whole pig’s skin to make. He put a strong rope in for lacings, that he might pull the shoe tightly together, and, finally, he armed himself with a couple of handspikes.

“Shortly he heard the trolls coming. They had a fiddler with them, and some began dancing, while others fell to eating the Christmas fare on the table,—some fried bacon, and some fried frogs and toads, and other nasty things which they had brought with them. During this some of the trolls found the shoe Peter had made. They thought it must belong to a very big foot. They all wanted to try it on at once, so they put a foot each into it; but Peter made haste and tightened the rope, took one of the handspikes and fastened the rope around it, and got them at last securely tied up in the shoe.

“Just then the bear put his nose out from behind the fireplace, where he was lying, and smelt they were frying something.

“‘Will you have a sausage, pussy?’ said one of the trolls, and threw a hot frog right into the bear’s jaws.

“‘Scratch them, pussy!’ said Peter.

“The bear got so angry that he rushed at the trolls and scratched them all over, while Peter took the other handspike and hammered away at them as if he wanted to beat their brains out. The trolls had to clear out at last, but Peter stayed and enjoyed himself with all the Christmas fare the whole week. After that the trolls were not heard of there for many years.

“Some years afterwards, about Christmas time, Peter was out in the forest cutting wood for the holidays, when a troll came up to him and shouted,—

“‘Have you got that big pussy of yours, yet?’

“‘Have you got that big pussy of yours, yet?’

“‘Oh, yes! she is at home behind the fireplace,’ said he; ‘and she has got seven kittens, all bigger and larger than herself.’

“‘We’ll never come to you any more, then,’ said the troll, and they never did.”

The children were all delighted with this story.

“Tell us another, dear Lieutenant,” they all shouted in chorus.

“No, no, children! you bother the Lieutenant too much,” said Miss Cicely. “Aunt Mette will tell you a story now.”

“Yes, do, auntie, do!” was the general cry.

“I don’t know exactly what I shall tell you,” said Aunt Mette, “but since we have commenced telling about the brownies, I think I will tell you something about them, too. You remember, of course, old Kari Gausdal, who came here and baked bread, and who always had so many tales to tell you.”

“Oh, yes, yes!” shouted the children.

“Well, old Kari told me that she was in service at the orphan asylum some years ago, and at that time it was still more dreary and lonely in that part of the town than it is now. That asylum is a dark and dismal place, I can tell you. Well, when Kari came there she was cook, and a very smart and clever girl she was. She had, one day, to get up very early in the morning to brew, when the other servants said to her,—

“‘You had better mind you don’t get up too early, and you mustn’t put any fire under the copper before two o’clock.’

“‘Why?’ she asked.

“‘Don’t you know there is a brownie here? And you ought to know that those people don’t like to be disturbed so early,’ they said; ‘and before two o’clock you mustn’t light the fire by any means.’

“‘Don’t you know there is a brownie here? And you ought to know that those people don’t like to be disturbed so early,’ they said; ‘and before two o’clock you mustn’t light the fire by any means.’

“‘Is that all?’ said Kari. She was anything but chicken-hearted. ‘I have nothing to do with that brownie of yours, but if he comes in my way, why, by my faith, I will send him head over heels through the door.’

“The others warned her, but she did not care a bit, and next morning, just as the clock struck one, she got up and lighted the fire under the copper in the brewhouse; but the fire went out in a moment. Somebody appeared to be throwing the logs about on the hearth, but she could not see who it was. She gathered the logs together, one at a time, but it was of no use, and the chimney would not draw, either. She got tired of this at last, took a burning log and ran around the room with it, swinging it high and low while she shouted, ‘Be gone, be gone whence you came! If you think you can frighten me you are mistaken.’ ‘Curse you!’ somebody hissed in one of the darkest corners. ‘I have had seven souls in this house; I thought I should have got eight in all!’ ‘But from that time nobody saw or heard the brownie in the asylum,’ said Kari Gausdal.”

“I am getting so frightened!” said one of the children. “No, you must tell us some more stories, Lieutenant; I never feel afraid when you tell us anything, because you tell us such jolly tales.” Another proposed that I should tell them about the brownie who danced the Halling dance with the lassie. That was a tale I didn’t care much about, as there was some singing in it. But they would on no account let me off, and I was going to clear my throat and prepare my exceedingly inharmonious voice to sing the Halling dance, which belongs to the story, when the pretty niece, whom I have already referred to, entered the room, to the great joy of the children and to my rescue.

“Well, my dear children, I will tell you the story, if you can get cousin Lizzie to sing the Halling for you,” said I, as she sat down, “and then you’ll dance to it yourselves, won’t you?”

Cousin Lizzie was besieged by the children, and had to promise to do the singing, so I commenced my story.

“There was, once upon a time,—I almost think it was in Hallingdal,—a lassie who was sent up into the hay-loft with the cream porridge for the brownie,—I cannot recollect if it was on a Thursday or on a Christmas Eve, but I think it was a Christmas Eve. Well, she thought it was a great pity to give the brownie such a dainty dish, so she ate the porridge herself, and the melted butter in the bargain, and went up into the hay-loft with the plain oatmeal porridge and sour milk, in a pig’s trough instead. ‘There, that’s good enough for you, Master Brownie,’ she said. But no sooner had she spoken the words than the brownie stood right before her, seized her round the waist, and danced about with her, which he kept up till she lay gasping for breath, and when the people came up into the hay-loft in the morning, she was more dead than alive. But as long as they danced, the brownie sang,” (and here Cousin Lizzie undertook his part, and sang to the tune of the Halling)—

“There was, once upon a time,—I almost think it was in Hallingdal,—a lassie who was sent up into the hay-loft with the cream porridge for the brownie,—I cannot recollect if it was on a Thursday or on a Christmas Eve, but I think it was a Christmas Eve. Well, she thought it was a great pity to give the brownie such a dainty dish, so she ate the porridge herself, and the melted butter in the bargain, and went up into the hay-loft with the plain oatmeal porridge and sour milk, in a pig’s trough instead. ‘There, that’s good enough for you, Master Brownie,’ she said. But no sooner had she spoken the words than the brownie stood right before her, seized her round the waist, and danced about with her, which he kept up till she lay gasping for breath, and when the people came up into the hay-loft in the morning, she was more dead than alive. But as long as they danced, the brownie sang,” (and here Cousin Lizzie undertook his part, and sang to the tune of the Halling)—

"And you have eaten the porridge for the brownie, And you shall dance with the little brownie! "And have you eaten the porridge for the brownie? Then you shall dance with the little brownie!"

I assisted in keeping time by stamping on the floor with my feet, while the children romped about the room in uproarious joy.

“I think you are turning the house upside down, children!” said old Mother Skau; “if you’ll be quiet, I’ll give you a story.”

The children were soon quiet, and Mother Skau commenced as follows:

“You hear a great deal about brownies and fairies and such like beings, but I don’t believe there is much in it. I have neither seen one nor the other. Of course I have not been so very much about in my lifetime, but I believe it is all nonsense. But old Stine out in the kitchen there, she says she has seen the brownie. About the time when I was confirmed she was in service with my parents. She came to us from a captain’s, who had given up the sea. It was a very quiet place. The captain only took a walk as far as the quay every day. They always went to bed early. People said there was a brownie in the house. Well, it so happened that Stine and the cook were sitting in their room one evening, mending and darning their things; it was near bedtime, for the watchman had already sung out ‘Ten o’clock!’ but somehow the darning and the sewing went on very slowly indeed; every moment ‘Jack Nap’ came and played his tricks upon them. At one moment Stine was nodding and nodding, and then came the cook’s turn,—they could not keep their eyes open; they had been up early that morning to wash clothes. But just as they were sitting thus, they heard a terrible crash down stairs in the kitchen, and Stine shouted, ‘Lor’ bless and preserve us! it must be the brownie.’ She was so frightened she dared scarcely move a foot, but at last the cook plucked up courage and went down into the kitchen, closely followed by Stine. When they opened the kitchen door they found all the crockery on the floor, but none of it broken, while the brownie was standing on the big kitchen table with his red cap on, and hurling one dish after the other on to the floor, and laughing in great glee. The cook had heard that the brownies could sometimes be tricked into moving into another house when anybody would tell them of a very quiet place, and as she long had been wishing for an opportunity to play a trick upon this brownie, she took courage and spoke to him,—her voice was a little shaky at the time,—that he ought to remove to the tinman’s over the way, where it was so very quiet and pleasant, because they always went to bed at nine o’clock every evening; which was true enough, as the cook told Stine later, but then the master and all his apprentices and journeymen were up every morning at three o’clock and hammered away and made a terrible noise all day.

“You hear a great deal about brownies and fairies and such like beings, but I don’t believe there is much in it. I have neither seen one nor the other. Of course I have not been so very much about in my lifetime, but I believe it is all nonsense. But old Stine out in the kitchen there, she says she has seen the brownie. About the time when I was confirmed she was in service with my parents. She came to us from a captain’s, who had given up the sea. It was a very quiet place. The captain only took a walk as far as the quay every day. They always went to bed early. People said there was a brownie in the house. Well, it so happened that Stine and the cook were sitting in their room one evening, mending and darning their things; it was near bedtime, for the watchman had already sung out ‘Ten o’clock!’ but somehow the darning and the sewing went on very slowly indeed; every moment ‘Jack Nap’ came and played his tricks upon them. At one moment Stine was nodding and nodding, and then came the cook’s turn,—they could not keep their eyes open; they had been up early that morning to wash clothes. But just as they were sitting thus, they heard a terrible crash down stairs in the kitchen, and Stine shouted, ‘Lor’ bless and preserve us! it must be the brownie.’ She was so frightened she dared scarcely move a foot, but at last the cook plucked up courage and went down into the kitchen, closely followed by Stine. When they opened the kitchen door they found all the crockery on the floor, but none of it broken, while the brownie was standing on the big kitchen table with his red cap on, and hurling one dish after the other on to the floor, and laughing in great glee. The cook had heard that the brownies could sometimes be tricked into moving into another house when anybody would tell them of a very quiet place, and as she long had been wishing for an opportunity to play a trick upon this brownie, she took courage and spoke to him,—her voice was a little shaky at the time,—that he ought to remove to the tinman’s over the way, where it was so very quiet and pleasant, because they always went to bed at nine o’clock every evening; which was true enough, as the cook told Stine later, but then the master and all his apprentices and journeymen were up every morning at three o’clock and hammered away and made a terrible noise all day. Since that day they have not seen the brownie any more at the captain’s. He seemed to feel quite at home at the tinman’s, although they were hammering and tapping away there all day; but people said that the gude-wife put a dish of porridge up in the garret for him every Thursday evening, and it’s no wonder that they got on well and became rich when they had a brownie in the house. Stine believed he brought things to them. Whether it was the brownie or not who really helped them, I cannot say,” said Mother Skau, in conclusion, and got a fit of coughing and choking after the exertion of telling this, for her, unusually long story.

Since that day they have not seen the brownie any more at the captain’s. He seemed to feel quite at home at the tinman’s, although they were hammering and tapping away there all day; but people said that the gude-wife put a dish of porridge up in the garret for him every Thursday evening, and it’s no wonder that they got on well and became rich when they had a brownie in the house. Stine believed he brought things to them. Whether it was the brownie or not who really helped them, I cannot say,” said Mother Skau, in conclusion, and got a fit of coughing and choking after the exertion of telling this, for her, unusually long story.

When she had taken a pinch of snuff she felt better, and became quite cheerful again, and began:— “My mother, who, by the way, was a truthful woman, told a story which happened here in the town one Christmas Eve. I know it is true, for an untrue word never passed her lips.” “Let us hear it, Madame Skau,” said I. “Yes, tell, tell, Mother Skau!” cried the children. She coughed a little, took another pinch of snuff, and proceeded:—

“When my mother still was in her teens, she used sometimes to visit a widow whom she knew, and whose name was,—dear me, what was her name?—Madame,—yes, Madame Evensen, of course. She was a woman who had seen the best part of her life, but whether she lived up in Mill Street or down in the corner by the Little Church Hill, I cannot say for certain. Well, one Christmas Eve, just like to-night, she thought she would go to the morning service on the Christmas Day, for she was a great church-goer, and so she left out some coffee with the girl before she went to bed, that she might get a cup next morning,—she was sure a cup of warm coffee would do her a great deal of good at that early hour. When she woke, the moon was shining into the room; but when she got up to look at the clock she found it had stopped and that the fingers pointed to half-past eleven. She had no idea what time it could be, so she went to the window and looked across to the church. The light was streaming out through all the windows. She must have overslept herself! She called the girl and told her to get the coffee ready, while she dressed herself. So she took her hymn-book and started for church. The street was very quiet; she did not meet a single person on her way to church. When she went inside, she sat down in her customary seat in one of the pews, but when she looked around her she thought that the people were so pale and so strange,—exactly as if they were all dead. She did not know any of them, but there were several of them she seemed to recollect having seen before; but when and where she had seen them she could not call to mind. When the minister came into the pulpit, she saw that he was not one of the ministers in the town, but a tall, pale man, whose face, however, she thought she could recollect. He preached very nicely indeed, and there was not the usual noisy coughing and hawking which you always hear at the morning services on a Christmas Day; it was so quiet, you could have heard a needle drop on the floor,—in fact, it was so quiet she began to feel quite uneasy and uncomfortable. When the singing commenced again, a female who sat next to her leant towards her and whispered in her ear, ‘Throw the cloak loosely around you and go, because if you wait here till the service is over they will make short work of you. It is the dead who are keeping service.'”

When she woke, the moon was shining into the room; but when she got up to look at the clock she found it had stopped and that the fingers pointed to half-past eleven. She had no idea what time it could be, so she went to the window and looked across to the church. The light was streaming out through all the windows. She must have overslept herself! She called the girl and told her to get the coffee ready, while she dressed herself. So she took her hymn-book and started for church. The street was very quiet; she did not meet a single person on her way to church. When she went inside, she sat down in her customary seat in one of the pews, but when she looked around her she thought that the people were so pale and so strange,—exactly as if they were all dead. She did not know any of them, but there were several of them she seemed to recollect having seen before; but when and where she had seen them she could not call to mind. When the minister came into the pulpit, she saw that he was not one of the ministers in the town, but a tall, pale man, whose face, however, she thought she could recollect. He preached very nicely indeed, and there was not the usual noisy coughing and hawking which you always hear at the morning services on a Christmas Day; it was so quiet, you could have heard a needle drop on the floor,—in fact, it was so quiet she began to feel quite uneasy and uncomfortable. When the singing commenced again, a female who sat next to her leant towards her and whispered in her ear, ‘Throw the cloak loosely around you and go, because if you wait here till the service is over they will make short work of you. It is the dead who are keeping service.'”

“Oh, Mother Skau, I feel so frightened, I feel so frightened!” whimpered one of the children, and climbed up on a chair.

“Hush, hush, child!” said Mother Skau. “She got away from them safe enough; only listen! When the widow heard the voice of the person next to her, she turned round to look at her,—but what a start she got! She recognized her; it was her neighbour who died many years ago; and when she looked around the church, she remembered well that she had seen both the minister and several of the congregation before, and that they had died long ago. This sent quite a cold shiver through her, she became that frightened. She threw the cloak loosely round her, as the female next to her had said, and went out of the pew; but she thought they all turned round and stretched out their hands after her. Her legs shook under her, till she thought she would sink down on the church floor. When she came out on the steps, she felt that they had got hold of her cloak; she let it go and left it in their clutches, while she hurried home as quickly as she could. When she came to the door the clock struck one, and by the time she got inside she was nearly half dead,—she was that frightened. In the morning when the people went to church, they found the cloak lying on the steps, but it was torn into a thousand pieces. My mother had often seen the cloak before, and I think she saw one of the pieces, also; but that doesn’t matter,—it was a short, pink, woollen cloak, with fur lining and borders, such as was still in use in my childhood. They are very rarely seen nowadays, but there are some old ladies in the town and down at the ‘Home’ whom I see with such cloaks in church at Christmas time.”

“Hush, hush, child!” said Mother Skau. “She got away from them safe enough; only listen! When the widow heard the voice of the person next to her, she turned round to look at her,—but what a start she got! She recognized her; it was her neighbour who died many years ago; and when she looked around the church, she remembered well that she had seen both the minister and several of the congregation before, and that they had died long ago. This sent quite a cold shiver through her, she became that frightened. She threw the cloak loosely round her, as the female next to her had said, and went out of the pew; but she thought they all turned round and stretched out their hands after her. Her legs shook under her, till she thought she would sink down on the church floor. When she came out on the steps, she felt that they had got hold of her cloak; she let it go and left it in their clutches, while she hurried home as quickly as she could. When she came to the door the clock struck one, and by the time she got inside she was nearly half dead,—she was that frightened. In the morning when the people went to church, they found the cloak lying on the steps, but it was torn into a thousand pieces. My mother had often seen the cloak before, and I think she saw one of the pieces, also; but that doesn’t matter,—it was a short, pink, woollen cloak, with fur lining and borders, such as was still in use in my childhood. They are very rarely seen nowadays, but there are some old ladies in the town and down at the ‘Home’ whom I see with such cloaks in church at Christmas time.”

The children, who had expressed considerable fear and uneasiness during the latter part of the story, declared they would not hear any more such terrible stories. They had crept up into the sofa and on the chairs, but still they thought they felt somebody plucking at them from underneath the table. Suddenly the lights were brought in, and we discovered then, to our great amusement, that the children had put their legs on to the table. The lights, the Christmas cake, the jellies, the tarts and the wine soon chased away the horrible ghost story and all fear from their minds, revived everybody’s spirits, and brought the conversation on to their neighbours and the topics of the day. Finally, our thoughts took a flight towards something more substantial, on the appearance of the Christmas porridge and the roast ribs of pork. We broke up early, and parted with the best wishes for a Merry Christmas. I passed, however, a very uneasy night. I do not know whether it was the stories, the substantial supper, my weak condition, or all these combined, which was the cause of it; I tossed myself hither and thither in my bed, and got mixed up with brownies, fairies and ghosts the whole night. Finally, I sailed through the air towards the church, while some merry sledge-bells were ringing in my ears. The church was lighted up, and when I came inside I saw it was our own church up in the valley. There were nobody there but peasants in their red caps, soldiers in full uniform, country lasses with their white head-dresses and red cheeks. The minister was in the pulpit; it was my grandfather, who died when I was a little boy. But just as he was in the middle of the sermon, he made a somersault—he was known as one of the smartest men in the parish—right into the middle of the church; the surplice flew one way and the collar another. “There lies the parson, and here am I,” he said, with one of his well-known airs, “and now let us have a spring dance!” In an instant the whole of the congregation was in the midst of a wild dance. A big tall peasant came towards me and took me by the shoulder and said, “You’ll have to join us, my lad!”

At this moment I awoke, and felt some one pulling at my shoulder. I could scarcely believe my eyes when I saw the same peasant whom I had seen in my dream leaning over me. There he was, with the red cap down over his ears, a big fur coat over his arm, and a pair of big eyes looking fixedly at me.

“You must be dreaming,” he said, “the perspiration is standing in big drops on your forehead, and you were sleeping as heavily as a bear in his lair! God’s peace and a merry Christmas to you, I say! and greetings to you from your father and all yours up in the valley. Here’s a letter from your father, and the horse is waiting for you out in the yard.”

“But, good heavens! is that you, Thor?” I shouted in great joy. It was indeed my father’s man, a splendid specimen of a Norwegian peasant. “How in the world have you come here already?”

“Ah! that I can soon tell you,” answered Thor. “I came with your favourite, the bay mare. I had to take your father down to Næs, and then he says to me, ‘Thor,’ says he, ‘it isn’t very far to town from here. Just take the bay mare and run down and see how the Lieutenant is, and if he is well and can come back with you, you must bring him back along with you,’ says he.”

When we left the town it was daylight. The roads were in splendid condition. The bay mare stretched out her old smart legs, and we arrived at length in sight of the dear old house. Thor jumped off the sledge to undo the gate, and as we merrily drove up to the door we were met by the boisterous welcome of old Rover, who, in his frantic joy at hearing my voice, almost broke his chains in trying to rush at me.

When we left the town it was daylight. The roads were in splendid condition. The bay mare stretched out her old smart legs, and we arrived at length in sight of the dear old house. Thor jumped off the sledge to undo the gate, and as we merrily drove up to the door we were met by the boisterous welcome of old Rover, who, in his frantic joy at hearing my voice, almost broke his chains in trying to rush at me.

Such a Christmas as I spent that year I cannot recollect before or since.

The End.