Remembering Renay: On Growing Up With an Unforgettable Mother

This Sunday morning, the final hot Sunday of May, there are two matters foremost on my mind, creeping like those water stains down from the Roach House ceiling. I cannot escape this terrible feeling deep in my soul. This certainty. This knowing.

I would be underdressed for an awards show.

Recently it was announced at school, much to my shame, that I am to collect a poetry prize—not a school-wide prize, mind you, but county-wide. The prize is considerable, fifty dollars, and that part is fucking great. Fifty dollars is a ton of money, the Corren family equivalent of striking gold. My poem, hastily composed during an arts assembly with a prestigious visiting poet from esteemed Chapel Hill, had been scribbled with the express intent of making my mother laugh until she farted, which, as everybody knows, is the best kind of laugh.

Called “My Behind,” it was littered with in-jokes about distant fathers, cold butts, a functioning toilet seat. It was so stupid, I knew it would make Renay guffaw-fart. And lo and behold, I won a contest for it. But the Fayetteville Arts Council seems determined to deepen my shame by placing my stupid butt poem onto every bus in Fayetteville. My butt poem, just circling and circling around Fayetteville on the side of all nine buses. With my name attached to it for all to see.

I was acting responsibly, responding as a child would, to a dire need for maternal survival, doing it as urgently and as often as required.

And I have not a thing to wear to the Arts Council awards.

All my clothes are rags or hand-me-downs. I don’t own a stitch of couture. Not one Valentino. No Balmain. Not even a fucking Wrangler.

Nothing you’d want to wear in front of a prestigious Chapel Hill lady poet who smoked a corn cob pipe.

“I need jeans,” I moan somberly to my mother’s ceiling. “I need some Jordache jeans.”

When I thought about simply holding a pair of freshly ironed Jordache jeans in my ink-stained hands—not the ratty, label-less hand-me-downs from Asshole and Twin that I begrudgingly wore—actual, new-smelling, stiff Jordache jeans directly off the rack, I physically ached with longing.

Renay thumb-cracks a crisp page with a practiced flick of her reading wrist, ignoring me while juggling the hardback copy of Judith Krantz’s Princess Daisy and her eyebrow-plucking mirror.

“Uh-huh,” she says in her noncommittal and unhelpful parenting mode.

Published the year before, Princess Daisy, a thick, juicy, semi-incestuous saga, is still seducing women and closeted pastors from every newsstand and Winn-Dixie in town, and Renay has finally, triumphantly, carried it home from Tyler’s half-off. But instead of plowing through it in a single night as she ordinarily would, Renay has lingered over this book for an entire intolerable weekend. Two whole days. For one book!

And so I do my best to become part of the experience of reading it with her, gazing at the clearly postcoital blonde on the jacket, who coquettishly peers over her shoulder at me while clutching an expensive, diaphanous sheet. I slow my own breathing to match Renay’s as she thumb-cracks another page, and soon it is as though I was reading alongside her, inhaling every word, exhaling every scandalous twist and turn until our heartbeats become one and we are joined, a depraved metronome of book-inhaling trash and lust and sin, all of it flying off the page as we cram those creamy, delicious scenes into our mouths like rich, buttery scones. She and I have never had a scone, but it matters little, as we are suddenly skiing down the Alps together, and then the slopes of Biarritz together, places we have never been and will never go, but navigate now with insouciant ease, and then we are chauffeured off the base of this powdery mountain, soon skimming the brisk waters along the Monterey Bay coastline, laughing beneath the Santa Cruz lighthouse on a three-masted sailboat of a type we will never board, and have never even seen, but there we are anyway, sailing, skiing, schussing together, rich-as-shit best friends dripping in fur, loving every buttery second.

From my earliest days, I read what she read, as soon as she put it down. We had an ongoing book club that began when she opened her eyes, still smudged with purple or scarlet shadow, and ended when she was finally released by her kidnapper, insomnia. We read every moment we could. In addition to Judith Krantz, we were ardent admirers of the great Jackie Collins, Sidney Sheldon, and of course the Edith Wharton of incest, Miss Cleo Virginia “V. C.” Andrews. We just loved to curl up with those Dollanganger siblings, a family that was, at a minimum, eleven or twelve thousand times more fucked-up than our own—and they had money and doughnuts!

At twelve, I read as fast as Renay, and as wolfishly, indiscriminately.

So I am of course desperate to pry the flashy, filthy new Judith Krantz out of her sharp, perfectly filed claws. Renay knows how much I love Judith Krantz, and she lords that racy tome above me in a ritual of withholding and ostentatious slow page-turning by indolent thumb-flick, thumb-flick, thumb-flick.

A real Krantz bitch-heroine thing to do, if you ask me.

Renay, like me, has been waiting a long time to have this new, exciting Krantz in her mitts, and after such a lustful and suspenseful wait she isn’t about to waste the special effect of being seen carrying it around. To be seen with Judith, may her name forever be a blessing, to be seen with Judith in hardback—well, you must be some kind of classy, in-the-know Fayetteville society lady from up in Haymount, probably, and you are just lost or stumbled your way behind that counter at B&B Lanes by accident. You are danged right Renay took her time being seen with all that. Princess Daisy was power.

Renay could read anywhere. At work. At home. The toilet, obviously.

But less obviously, and of course dangerously: in her car at any length of stoplight, out delivering newspapers, at the Sunoco, pier fishing, at the casino, at the Shoney’s, watching TV, standing in front of a microwave, seated anywhere, because that woman loved nothing more than a good, long sit. My fondest memories of childhood are of dozing like a curled shrimp against my mother’s big butt, my toes wrapped inside her massive, gnarled troll’s feet while she flick-flick-flicked her way through a book a day. A Pietà of mother and son, afloat on trashy worlds, heated beds, and sultry words fashioned by wealthy women ensconced in far-off, cultured Beverly Hills.

We made monthly pilgrimages to our cathedral, that corrugated palace of pulp on the Champs-Elysees of Fayetteville, Yadkin Road: Edward McKay’s Used Books. There we would sell off Renay’s discards—usually, thirty or more books—and load up our wrinkled grocery bags full of other people’s cast-offs, one bag for Renay, one bag for me, books we paid for by the pound, not the title, and which we would then spend the next month haggling over. “I’ll trade you my copy of Cujo if you give me your copy of Bloodline” is usually how this great game unfolded, before we descended into bitter recriminations over who really had the temperament for Tom Wolfe and who didn’t, and inevitably an unseemly screaming match over the single prized copy of the magnificent Shelley Winters biography Shelley: Also Known as Shirley.

Renay is humming and plowing her way through the final three chapters of the new Krantz and she seems…happy? It is, after all, not her name that is going to be appearing on buses all summer next to a poem called “My Behind.” She isn’t the one begging for a pair of fresh Jordache jeans. She kicks me a little with her stuck- in-the-afghan foot, wiggling a pungent toe that still steams of sweaty bowling alley sock, urgently whispering, “Ann, rub my feet. Please, my feet hurt so bad.”

Now I am definitely awake.

If my mother’s hands are the beautiful people at the Biarritz ball, Renay’s feet are the flowers in the attic. It isn’t just that they are extra-extra wide, 10EEEE; it is because, between her job at B&B and managing the Sunoco, Renay stands on those planks more than sixteen hours a day, six or seven days a week. She is that person, doing the jobs that you have to stand for, that big lady doing that thing for you that you could never do, at that store you always go to, that lady who always makes you laugh. That lady made these feet, and they are treated as harshly as the bed of an old pickup. They are wider than they should be, calloused, her ankles strafed with deep, inflamed depressions from the straps of her shoes.

I get to work on massaging them—and am promptly rewarded with an enormous fart, rolled languidly upon my head. From my own mother, and with no warning at all. Renay’s farts were freely given, a benefaction unto all, always generously dispensed with her jovial wave.

Hers were happy farts, and one dared not recoil. Renay’s bleats were the beefy, thunderous variety, delivered upon cloudy blats of sound and fury typically only found in certain roomy, Ashkenazic women of the diaspora with those fashionably bulletproof bowels lined with decades of schmaltz.

“You will pay for this,” I whisper, glaring a low curse up at her.

“There. Yes!” she yelps. “On the knuckle. On it! Press harder.”

I bear down, but I am just a weakling, the runt of Renay’s brood.

Even my farts are tiny peeps. Her big toe is swollen beyond recognition.

The help it requires is far outside the reach of my meager, albeit celebrated, massage skills. Yet just when it seems like I will have to give up, I manage to wedge one of my boiled chicken bone-weak fingers deep into Renay’s toe, and she sort of seizes, then kicks her head back against the waterbed frame, moaning in Princess Daisy levels of surrender and ecstasy, like she is thrashing in a Park Avenue penthouse, not on a ripped corduroy husband pillow half off from Kmart.

My own future happiness…was highly contingent upon Renay’s, so much so that my own dreams and my own sense of self, pleasure, or intimacy was practically nonexistent in the face of hers.

I get it.

I was a boy who called his father Shithead and massaged his mother’s toes.

I have cross-referenced all of these acts with my appropriately pricey but still wrong side of Union Square-adjacent therapist. Sam has helped me to understand that I was not in love with my mother, nor was I merely doing her bidding. I was acting responsibly, responding as a child would, to a dire need for maternal survival, doing it as urgently and as often as required, as I was taught to do from my very first minutes on this earth, when I was pincered from Renay’s womb and was not seen or touched by her again for the next two weeks, as she recovered from twin shocks of the neck-to-butt gutting Cesarean and the disappointment of another boy child. As Sam has explained, my own future happiness—my own survival—was highly contingent upon Renay’s, so much so that my own dreams and my own sense of self, pleasure, or intimacy was practically nonexistent in the face of hers.

Sam has reassured me that during episodes like this, I was just getting the tension out of my mother’s toe knuckle.

Because that made me feel better, too.

A potent cocktail of servitude and congenital desire to please the woman who had nearly died bringing me into the world and never let me forget it. Not once. Not ever.

Our massage sessions were therapeutic for both of us. Renay had a high threshold for pain, and I could use that as an outlet for expressing my rage. I would beat those garbage digits of hers down, making Renay’s toes the repository for all my emotional manifesting, our poverty, our used paperback books, the loss of our house on Pamalee Drive, the fact that we all called this place Roach House, and it wasn’t ironic.

“I am not going in front of Chapel Hill’s most important living poet wearing Asshole’s old jeans. It ain’t happening,” I say, bartering with two swollen toes smashed flat between my palms.

“Harder! Dig!” she shrieks into the calm of our Sunday morning, waking the roaches, but not my brothers.

“You’re coming tomorrow night,” I say, slapping at her ankle. It isn’t a question.

“I know,” Renay says, affecting an unconvincing offense that I would suggest otherwise. But I know better. My mother is not the plan ahead type.

“You forgot. It’s fine. I’m reminding you.” I sulk.

“Would I forget my little poet?” Renay’s mocking tone is appropriate for a poor poet who has written a terrible nine lines about a butt and a toilet, so I take no offense.

“It would be very poetic of you to forget your little poet,” I mock back, triumphantly.

“Forgetting that my distinguished poet child won a poetry award?

That would not be poetic, son. That would be ironic,” she corrects me—I would add, vindictively. But she speaks often in such a key when any of our accomplishments threaten to outshine or upstage her aggravation.

“Ow!” she yelps as I stab maniacally at her prematurely old-lady toe, the one that looks most like Popeye in repose, shoving the sharp end of a blue curling brush deep into what I now can only assume was her liver meridian.

“That! There! The fascia! Do it, Jewboy! Do the fascia!!” she screams.

As if I know what a goddamned fascia was.

__________________________________

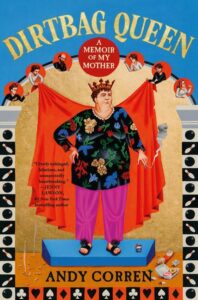

Excerpted from the book Dirtbag Queen by Andy Corren. Copyright © 2025 by Andy Corren. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.