Sherwood Anderson – The Work of Gertrude Stein

ONE evening in the winter, some years ago, my brother came to my rooms in the city of Chicago bringing with him a book by Gertrude Stein. The book was called Tender Buttons and, just at that time, there was a good deal of fuss and fun being made over it in American newspapers. I had already read a book of Miss Stein’s called Three Lives and had thought it contained some of the best writing ever done by an American. I was curious about this new book.

My brother had been at some sort of a gathering of literary people on the evening before and someone had read aloud from Miss Stein’s new book. The party had been a success. After a few lines the reader stopped and was greeted by loud shouts of laughter. It was generally agreed that the author had done a thing we Americans call “putting something across”—the meaning being that she had, by a strange freakish performance, managed to attract attention to herself, get herself discussed in the newspapers, become for a time a figure in our hurried, harried lives.

My brother, as it turned out, had not been satisfied with the explanation of Miss Stein’s work then current in America, and so he bought Tender Buttons and brought it to me, and we sat for a time reading the strange sentences. “It gives words an oddly new intimate flavor and at the same time makes familiar words seem almost like strangers, doesn’t it,” he said. What my brother did, you see, was to set my mind going on the book, and then, leaving it on the table, he went away.

And now, after these years, and having sat with Miss Stein by her own fire in the rue de Fleurus in Paris I am asked to write something by way of an introduction to a new book she is about to issue.

As there is in America an impression of Miss Stein’s personality, not at all true and rather foolishly romantic, I would like first of all to brush that aside. I had myself heard stories of a long dark room with a languid woman lying on a couch, smoking cigarettes, sipping absinthes perhaps and looking out upon the world with tired, disdainful eyes. Now and then she rolled her head slowly to one side and uttered a few words, taken down by a secretary who approached the couch with trembling eagerness to catch the falling pearls.

You will perhaps understand something of my own surprise and delight when, after having been fed up on such tales and rather Tom Sawyerishly hoping they might be true, I was taken to her to find instead of this languid impossibility a woman of striking vigor, a subtle and powerful mind, a discrimination in the arts such as I have found in no other American born man or woman, and a charmingly brilliant conversationalist.

“Surprise and delight” did I say? Well, you see, my feeling is something like this. Since Miss Stein’s work was first brought to my attention I have been thinking of it as the most important pioneer work done in the field of letters in my time. The loud guffaws of the general that must inevitably follow the bringing forward of more of her work do not irritate me but I would like it if writers, and particularly young writers, would come to understand a little what she is trying to do and what she is in my opinion doing.

My thought in the matter is something like this—that every artist working with words as his medium, must at times be profoundly irritated by what seems the limitations of his medium. What things does he not wish to create with words! There is the mind of the reader before him and he would like to create in that reader’s mind a whole new world of sensations, or rather one might better say he would like to call back into life all of the dead and sleeping senses.

There is a thing one might call “the extension of the province of his art” one wants to achieve. One works with words and one would like words that have a taste on the lips, that have a perfume to the nostrils, rattling words one can throw into a box and shake, making a sharp, jingling sound, words that, when seen on the printed page, have a distinct arresting effect upon the eye, words that when they jump out from under the pen one may feel with the fingers as one might caress the cheeks of his beloved.

And what I think is that these books of Gertrude Stein’s do in a very real sense recreate life in words.

We writers are, you see, all in such a hurry. There are such grand things we must do. For one thing the Great American Novel must be written and there is the American or English Stage that must be uplifted by our very important contributions, to say nothing of the epic poems, sonnets to my lady’s eyes, and what not. We are all busy getting these grand and important thoughts and emotions into the pages of printed books.

And in the meantime the little words, that are the soldiers with which we great generals must make our conquests, are neglected.

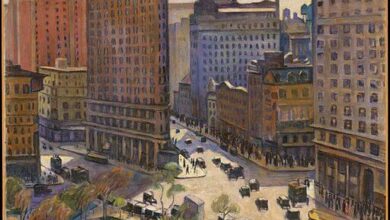

There is a city of English and American words and it has been a neglected city. Strong broad shouldered words, that should be marching across open fields under the blue sky, are clerking in little dusty dry goods stores, young virgin words are being allowed to consort with whores, learned words have been put to the ditch digger’s trade. Only yesterday I saw a word that once called a whole nation to arms serving in the mean capacity of advertising laundry soap.

For me the work of Gertrude Stein consists in a rebuilding, an entire new recasting of life, in the city of words. Here is one artist who has been able to accept ridicule, who has even forgone the privilege of writing the great American novel, uplifting our English speaking stage, and wearing the bays of the great poets, to go live among the little housekeeping words, the swaggering bullying street-corner words, the honest working, money saving words, and all the other forgotten and neglected citizens of the sacred and half forgotten city.

Would it not be a lovely and charmingly ironic gesture of the gods if, in the end, the work of this artist were to prove the most lasting and important of all the word slingers of our generation!