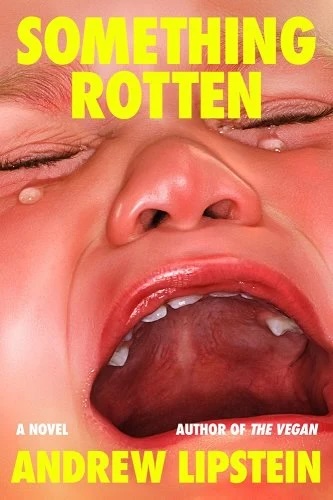

Something Rotten

What was he forgetting? He checked the list again, dragging his thumb down line by line, rummaging through the baby bag, suitcases, and carry-ons until he found each item: the squeeze packs, yes, the sleep sacks, yes, the pacifiers—The baby was crying. He looked up at it, still securely bound to the high chair (he was done eating but Reuben needed to buy some time), head now dipping to the side, tears mixing with snot, the goo taken from hand to shirt to table, the marble table they’d spent half a paycheck on—when they had that kind of money to spare—which had now fully absorbed the reds, yellows, and greens they fed the baby. The baby. It was the word that came to mind in moments like this, when this being, their son, their Arne, seemed not to be their future, the center of their life together and all that gave it meaning, but obligation incarnate. How could twenty pounds of flesh require so much? At times it seemed Arne required the entirety of their two lives—times like this, when his one life wasn’t enough.

He turned back to the list and Arne let out another cry. Reuben ignored him and tried to focus, but as he reread the word, Pacifiers, again and again, he realized he wasn’t focusing at all but seeing himself from a distance, from the vantage point of the doorway, where Cecilie might appear any second now, her bag over her shoulder, her skin tightened by the outside air, her face made up for the world to see. Reuben turned to look in the mirror, unknowingly adjusting his spine, legs, and chest to match the picture of himself he still held in his head. It was the first image he saw when he googled his name, the portrait taken nearly three years ago, when he was still someone who was occasionally photographed by professionals.

Pacifiers, he thought while the baby cried.

Pacifiers, he said out loud, repeating it to himself until he confirmed that he’d packed them. He did this with every item on the list, he racked his brain, he scoured the apartment, but still he sensed he was missing something. It wasn’t until he lay on the couch, closed his eyes, lifted the Juul from his shirt pocket, pulled as hard as his lungs could handle, and then revisited the image of Cecilie arriving—laying down her bag, freeing her curls, rushing toward Arne while whispering skat skat skat—that he found it: the milk. It wasn’t on the list because it wasn’t something they needed to bring; it was to be given to Arne before they left.

He looked at Arne, who was now pounding the table, momentarily distracted by his own anger, and then to the kitchen counter. This was where the bag of milk would be, defrosting, if he’d only remembered to defrost it. But he hadn’t, it was still in the freezer, and if its fount walked through the door right then he’d have to tell her that, for no reason at all, he’d forgotten to give their child the milk he needed to grow strong bones and ward off disease—forgotten even as a reminder belted from his baby’s lungs and filled the apartment, curling Reuben’s toes and fingers, shallowing his breath.

He shot up from the couch, grabbed a bag from the freezer, and ran the water until it was scalding. With the bag pinched between his fingers he brought it under the faucet, back and forth, the milk already starting to cloud and—The baby screamed and he turned, his body shifting just enough to move his thumb under the stream. The pain it brought was so deep a thin sheet of sweat materialized on his forehead, and around his neck, and after he himself screamed the apartment was, finally, silent. That is, except for the radio.

Had he turned it on? Who else could have? He’d been

here alone for eight hours now. Alone. Right: he wasn’t alone. Not just because he was with his son but because there was a whole community out there to support him. I’m not alone, that was his moms group’s battle cry, their—Right: parents group; it wasn’t just for moms, not in the year 2026, even though he was the only—

The jingle came through the radio, marking the hour. For years the song had been second nature to him; he’d often hummed along. But now he couldn’t wait for it to end, it sounded so psychotically chipper, twee, antiquated. He used to make Molly laugh by pretending to play a bugle while it rang through the office, a callback to a joke he’d made years before, that the song was originally performed by a chain of ferrets, each with a hand on their instrument, the other on the tail of the ferret in front of them. The anthem petered out and Molly’s voice filled the room, she was talking with a producer, trying not to laugh, it was supposed to sound like a hot mic. This had become her thing: the host who defied the flawlessness of her predecessors, who represented the authenticity of her generation. Reuben had once thought it was his generation, too, until they came up with terms to delineate the difference, and now he knew—oh, did he know—that the six years separating them was an unbridgeable chasm.

Without thinking, he had the Juul in his mouth again, the synthetic vapor coating his lungs and drying his throat. And by the time she was back to the script—teasing today’s show, lauding her forthcoming guests—he had so much nicotine in him he thought he might levitate. He even experienced, if just for a moment, a feeling akin to the sublime reset of a good night’s sleep. But the drug soon wore off, something happening faster by the day; it wasn’t two weeks ago that he’d bought the device, a spontaneous purchase on the way back from CVS, after Arne bit his shoulder, causing him to drop his iced coffee on his foot, the chilled liquid entering his Crocs from the top and settling between his foot and the sole. He hadn’t bothered to mention his acquisition to Cecilie, and when she finally caught him with it she stopped herself from bringing it up; she still hadn’t.

He pulled on it again, and again, but instead of relaxing him it only refined Molly’s voice, made it louder, made him feel she was in the apartment, beside him. He strode across the room, pushed aside the alocasia leaf guarding the radio, and turned it off. It felt good, how easily he could silence her, so he twisted the knob even more, forcing it past its limit.

He wondered whether there was such a thing as negative volume, he imagined what it might sound like, the inverse of Molly, the—

It snapped off. The knob was in his hand. He tried to find this funny until he realized he’d need to tell Cecilie what he’d done, and why, and then he threw the knob across the room. It hit the metal of the sink, the clank loud enough to make him wince, and then the baby was crying again.

Skat, he said, suddenly sorry, sorry for what he’d done and everything else. Skat skat skat, he said, apologizing, comforting Arne. Skat was the Danish word for darling, something he’d never utter in English. Technically it meant treasure. Also: tax.

Mom will be home soon, he said, and then again, in broken Danish: Mor vil hjem snart.

__________________________________

From Something Rotten by Andrew Lipstein . Used with permission of the publisher, FSG. Copyright © 2025.