The Annotated Nightstand: What Brandon Shimoda Is Reading Now, and Next

Recently, while at an outdoor train museum in Los Angeles, I stopped to read a large plaque that explained the space had been used as a concentration camp during the period of Japanese internment in the United States. (Always read the plaque.) Watching children crawl around the grounds’ trains with glee, it was a potent reminder that in country defined by colonial violence no place is innocent. That the colonized land was later used as a site of incarceration is merely a recent iteration of colonial oppression.

The irony that this place is called “Travel Town” is not lost on me. As the scholar Michael G. Kenny writes, “to recover the memory is also to name the culprit.”

As with Brandon Shimoda’s remarkable The Grave on the Wall, his new book The Afterlife Is Letting Go circles around monuments, memorialization, community trauma, incarceration, the innumerable violent expressions of power—and just as innumerable shapes of resistance. While Grave on the Wall predominantly focused on Shimoda’s grandfather, his new work is more expansive.

When describing the murder of James Hatsuaki Wakasa in 1943 at the Topaz concentration camp, Shimoda describes the moments before Wakasa’s death. He writes, “[Wakasa] had dinner with a friend in the mess hall that night—the stoves, dark brown with rust, are still there—then went for a walk along the southwestern edge of camp.”

This early quotation is the first of many gestures illustrative of Shimoda’s deep interest in collapsing time. The objects—in this case, the stoves—still remain from a time when a man was murdered with impunity while held in a concentration camp in a nation that considers itself one of the “free leaders of the world.” If the stoves are still here, what else endures? What else has survived but perhaps leaves no obvious physical trace?

Shimoda quotes many in The Afterlife If Letting Go, but aptly gives primacy to many Japanese and Japanese American witnesses, writers, thinkers, theorists, filmmakers, and artists. Within these pages are the historical plazas, plaques, museums, actions that attempt to honor, circumscribe, or wave away the pains and horrors exacted on Japanese people and Japanese Americans in the U.S.

Perhaps one of the most disturbing realities was for the children born in concentration camps and thus “into the impossible status of being simultaneously a citizen and an enemy of the United States.” Shimoda utilizes different forms to attend to all of this—some portions are almost entirely quotation, others are Shimoda’s descriptions of a museum or memorial or site as he moves through it.

The Afterlife Is Letting Go has the quality of quiet but intense scrutiny, like turning an object over and over to see how else it might catch the light. Such thoughtful rigor defines Shimoda’s work. In an interview with Tiffany Troy at Tupelo Quarterly, Shimoda states, “I have the attention span of a poet. Which means, to me, two things simultaneously: I can concentrate deeply and I’m constantly distracted. That’s my research process.”

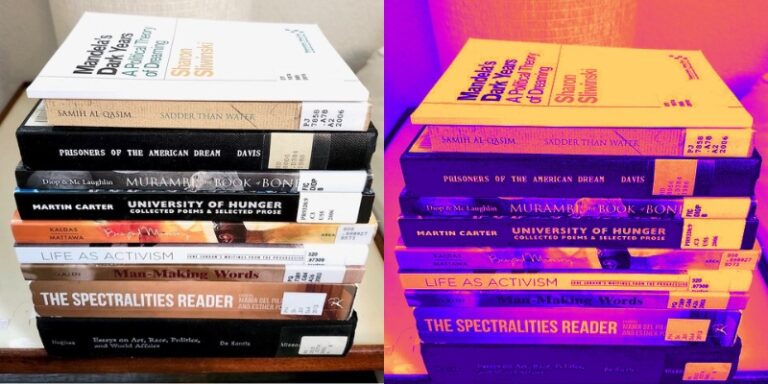

About his to-read pile, Shimoda says,

I like not knowing, or not exactly, where I’m going with the books I gather around/beside me. It’s like all reading is bibliomancy. At the center of this pile (at the bottom, in the picture) is Volume 9 of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, which includes Hughes’s reporting from the Spanish Civil War, October 1937 – February 1938. These articles, written for the Afro-American (Baltimore) and directly from the fight against fascism, are saying something specific to me, I can feel it. All the books on top of Hughes are related, in various ways, to what I hope to put together. For now, I’ve been thinking that I should become a journalist, although I’ve also been thinking: isn’t that what poets already are?

*

Sharon Sliwinski, Mandela’s Dark Years: A Political Theory of Dreaming

I *love* how all of these books are from the library. A reader after my own heart! (PS, support your librarians and local libraries—they’re doing god’s work.) Once again, we get to see an amazing U of Minnesota Press book among a guest’s stack.

Sliwinski wrote Mandela’s Dark Years after learning of a recurring nightmare Mandela experienced while imprisoned. Mandela writes in his autobiography (which Sliwinski quotes):

In the dream, I had just been released from prison—only it was not Robben Island, but a jail in Johannesburg. I walked outside the gates into the city and found no one there to meet me. In fact, there was no one there at all, no people, no cars, no taxis…Finally, I would see my home, but it turned out to be empty, a ghost house, with all the doors and windows open, but no one at all there.

Sliwinski writes, “[Mandela’s] nightmare seemed to attest something similarly poignant about his experience of prison, offering both a private account of his emotional state and a profound testimony about the political conditions of his unfreedom.”

Samih al-Qasim, Sadder Than Water: New and Selected Poems (trans. Nazih Kassis)

John Palattella writes in his Nation review of Sadder Than Water,

According to the late novelist Ghassan Kanafani, a poem of al-Qasim’s about the massacre of forty-eight Palestinian villagers by Israeli border guards in the town of Kafr Qasim in October 1956 was “memorized throughout the whole Galilee.” Al-Qasim, in fact, wrote several poems about Kafr Qasim, one of which is included in Sadder Than Water. It begins, “There is no monument, no rose, no memorial–/neither a line of poetry to delight the murdered/Nor any curtain for the unveiling.”

The diction of these lines is characteristic of many poems in the volume. It is bardic and ceremonial, addressed to a public event and determined to maintain an air of rhetorical grandeur.

Palettella goes on: “the experiences of indignity, humiliation, privation and misrepresentation…are the recurring subjects of Sadder Than Water, and al-Qasim explores them fruitfully.”

Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class

Davis’ epic book of LA history, City of Quartz, has been in my mental to-read pile for years—he clearly was a brilliant and important writer on nuanced topics of the world and politics. Socialist Review calls Prisoners of the American Dream “One of the most trenchant and original analyses of American politics.”

The jacket copy reads,

Prisoners of the American Dream is Mike Davis’s brilliant exegesis of a persistent and major analytical problem for Marxist historians and political economists: Why has the world’s most industrially advanced nation never spawned a mass party of the working class? This series of essays surveys the history of the American bourgeois democratic revolution from its Jacksonian beginnings to the rise of the New Right and the reelection of Ronald Reagan, concluding with some bracing thoughts on the prospects for progressive politics in the United States.

Boubacar Boris Diop, Murambi: The Book of Bones (trans. Fiona Mc Laughlin)

Diop’s novel is set during the Rwandan Genocide in April 1994. Eileen Julien writes in the book’s foreword:

What does a novel such as this bring to the awful violence of genocide that journalistic accounts and histories cannot? These forms of narrative are held to a well-known standard of truth. They are meant to establish and report facts, to offer an accurate and balanced, if not objective, representation of events. Murambi does contain such elements….

It does what a creative and transformative work alone can do. It distills this history and gives voice to those who can no longer speak—recovering, as best we can, the full, complex lives concealed in the statistics of genocide and rendering their humanity. In thinking about the gruesome murder of hundreds of thousands of people and this book—a frail object—we confront the enormous disproportion between the work of art, as beautiful and powerful as it may be, and the terrible events it symbolizes.

Yet it is through the work of imagination and language that the novel reconstitutes those unique human beings, now lost to us, and allows them nonetheless to survive and to be heard. Their stories may lead us to reflect on the practice of evil and help us claim our very own humanity amidst the routine banality of violence, the numbed indifference or silent acquiescence of which we are all a part.

Martin Carter, Gemma Robinson (editor), University of Hunger: Collected Poems & Selected Prose

In The Caribbean Review of Books, Vahni Capildeo describes of how colonization defined much of popular literature in the Caribbean, writing,

[I]t is still unusual for a Caribbean critic to find her- or himself writing about an unquestionably great writer—technically great, and great in inspiring others—who is also local, and lives within living memory….The relatively early anthologization of Carter’s poems and their inclusion in the curriculum means that many readers-become-writers learned of the work in the classroom, then went on to read further, but with those words and that thought already working in their pre-critical memories, formative of the spirit and the mind.Capildeo goes on to say,

What Robinson’s edition offers, in being as nearly comprehensive as possible, is—for the first time—the chance to see the span of Carter’s life’s work, and slowly to arrive at a new understanding of that totality, the physical book between one’s hands allowing the imagination to move between, weave and re-weave the times and spaces of the poems.

Pauline Kaldas (editor), Khaled Mattawa (editor), Beyond Memory: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Creative Nonfiction

Kaldas and Mattawa write in their introduction to Beyond Memory (published at Medium):

Although particular to their authors’ experiences, Arab American life stories have become emblematic of what it means to have one’s identity misconstrued in America and to have to fight to assert one’s humanity. For the last half century or so, Arab Americans have been pushed to the margins of society, have had their names and images distorted, their beliefs misrepresented, and their histories denied. Arab American writers, as these essays demonstrate, are well aware that telling their stories has becomes an act of speaking truth to resist and empower others….

[W]hen one refuses to be coopted and insists on rendering their experience as they understand it, the opportunities to speak can be lost, and the retributions can be devastating. Arab American writers share their stories of struggle and sacrifice as cautionary tales and to strip away illusions regarding the cultural politics of our country.

June Jordan, Stacy Russo (editor), Life as Activism: June Jordan’s Writing from The Progressive

This volume collects Jordan’s essays she wrote for The Progressive magazine between 1989-2001. It feels apt to quote from Barbara Ran’s obituary on Jordan after Jordan’s death in The Progressive. Ran writes,

Jordan not only gave me a greater sense of my identity as a black woman in a world dominated by white men, she also gave me, more importantly, a sense of connection with, and obligation to, a world much larger than my own. She was an internationalist and a humanitarian and fought for a definition of feminism that reflected a large and inclusive vision.”

Ran goes on to state,

It was the Palestinian struggle for self-government and dignity that captured June Jordan’s passion in the later years of her life. In 1996 she traveled to Lebanon where she wrote about the devastating militarism that had scarred the region. Jordan described the Palestinian struggle as “the moral litmus test” of her life. “I can’t think of another subject in the world today or in our United States that people approach with more trepidation and fear than that,” she explained in an interview in 2000….[T]he memory of June Jordan reminds us of the importance of speaking truth to power.

If you need a quick reminder of Jordan’s powerful prose, I always love to read “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America: Something like a sonnet for Phillis Wheatley.”

Nicolás Guillén, Man-Making Words: Selected Poems (trans. Roberto Marquez and David Arthur McMurray)

The Afro-Cuban twentieth century poet Nicolás Guillén was a premier contributor to the Négritude movement and friend of Langston Hughes. Aaron Coleman writes of Guillén in Poetry:

Both of his parents, Argelia Batista y Arrieta and Nicolás Guillén y Urra, were of African and European ancestry. At age fifteen, Guillén—the oldest of six siblings—suffered the sudden loss of his father, a liberal political figure, who was assassinated by government forces for protesting electoral fraud. As a young adult, Guillén was immersed in the island’s politics and burgeoning print culture….

Guillén’s best-known poems first appeared in 1930 in Diario de la marina, one of the country’s leading newspapers. Published as a suite titled Motivos de son —which I might translate as “motives of son” or “motifs of son”—they were both a roaring success and a scandal because they flouted the expectations of traditional poetry. Indeed, Guillén was a consummate maker and breaker of forms. The innovative poet rose swiftly to fame as he transformed the popular Cuban musical form of the son into a poetic form that called attention to the experiences of Afro-Cuban people and broke racial taboos.

María del Pilar Blanco (editor), Esther Peeren (editor), The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory

As someone who has deeply nerded out on scholarship regarding ghosts/hauntology/etc (à la Derrida, Avery Gordon, Grace M. Cho, and many others), this book sounds incredible. This is the jacket copy:

The Spectralities Reader is the first volume to collect the rich scholarship produced in the wake of the “spectral turn” of the early 1990s, which saw ghosts and haunting conjured as compelling analytical and methodological tools across the humanities and social sciences. Surveying the past twenty years from an interdisciplinary and cross-cultural perspective, the Reader displays the wide range of concerns spectrality, in its diverse elaborations, has been called upon to elucidate. The disjunctions produced by globalization, the ungraspable quality of modern media, the convolutions of subject formation (in terms of gender, race, and sexuality), the elusiveness of spaces and places, and the lingering presences and absences of memory and history have all been reconceived by way of the spectral.

Langston Hughes, Christopher C. De Santis (editor), The Collected Works of Langston Hughes: Essays on Art, Race, Politics, and World Affairs

In write-up of the edited collection in Kansas Alumni Magazine, Steven Hill shines a lovely light on Hughes and this volume’s editor, De Santis. Hill quotes from De Santis, who explains,

Though Hughes wrote in isolation, he was a very social person. He loved talking to people. He really was an infectious conversationalist, and I think that comes through in this book. The excitement, the exuberance of meeting new people through those travels and conversations, is palpable in this writing….To discover that, at the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance, in the early ’30s, Hughes was a regular contributor to a little magazine, kind of a newsletter really, published by the Harlem branch of the New York YMCA, and that he wrote weekly columns addressing what was going on with Black art and Black literature, and to see some of those original publications, was a wonderful part of this research.

De Santis goes on to say,

I think we see a different sense of humor coming out in the new material in this book. That’s tied to how we understand him as a blues writer, as a poet deeply influenced by the blues, whose first novel is certainly about serious subjects but is infused, like all his work, with a blues tone, a sense of the importance of finding a way to laugh, perhaps to draw yourself out of a kind of constant state of the misery of oppression.