Taiwan Travelogue

Bí-Thai-Baˈ k / Silver Needle Vermicelli

“Is there something good to eat around here?” “Hm?”

“Is that not what Aoyama-sensei was thinking?”

“Oh—did I say it out loud?”

I’d been so busy scribbling away in my notebook that I wasn’t even aware of having voiced the thought. I stopped writing and looked up at Chi-chan across the dining table.

Chi-chan was the nickname by which I referred to her in the privacy of my mind; in reality, I called her by the more proper Chizuru-san, but I found it disorienting to think of her as such given the overlap in our names. Since she was born in the sixth year of Taishō and therefore was four years younger, I used my seniority as an excuse to nickname her as endearingly as I pleased. Chi-chan it is!

Chi-chan’s dimples appeared. “No, Aoyama-sensei did not have to say so out loud. Perhaps you are not aware of this, but ‘Is there something good to eat around here?’ is rather a pet phrase of yours.”

“Ha! A glutton can’t hide her true colors!” I put down my pencil and began snacking on the deep-fried fava beans on the table between us.

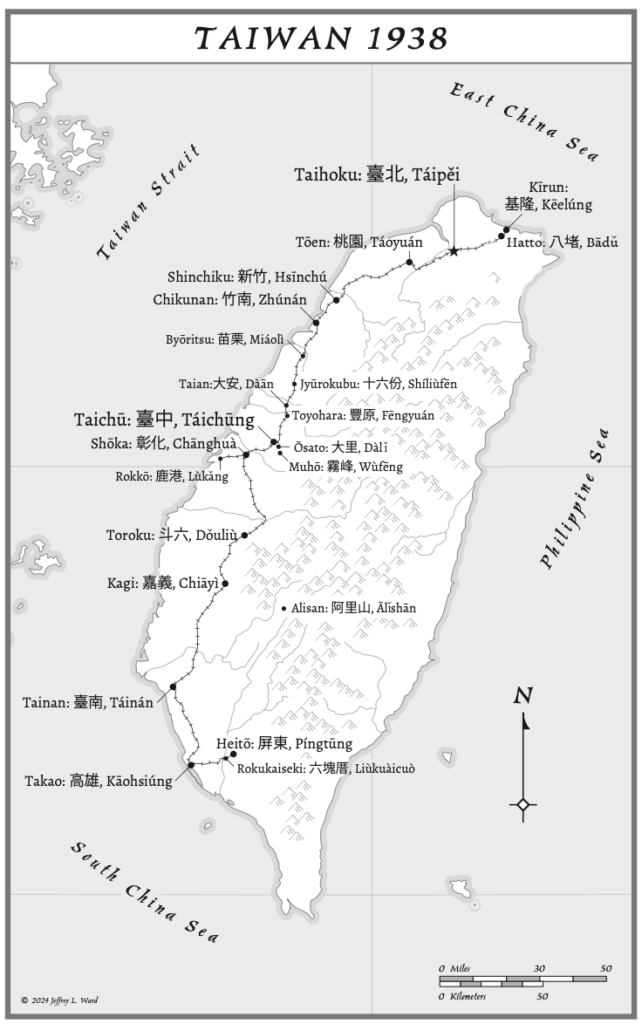

The notes that I’d been so diligently taking were on Taiwan’s railway system as explained to me by Chi-chan. Kīrun Station in the north, Takao Station in the south. At Chikunan Station, which was located in the south of Shinchiku Prefecture, the rail forked into two lines—the Coastal Line and the Mountain Line—that then merged again at Shōka Station. To reach Taichū Station as I did on my first day, one had to take the Mountain Line, which is also known as the Taichū Line.

I hadn’t quite decided whether any of this admittedly dry information would be useful for writing fiction, but my hands were quicker to act than my brain, and soon I was filling page after page with smudged pencil script. A writer’s reflex, I supposed. Chi-chan had also been telling me about some recent history. In the tenth year of Shōwa, almost three years before I arrived in Taiwan, a disaster known as the Great Shinchiku-Taichū Earthquake led to countless casualties and collapsed buildings, including one of the major bridges and a tunnel on the Taichū Line. The current railway was an emergency replacement. Despite this, I hadn’t noticed anything out of the ordinary on my first ride. No doubt it was thanks to the tireless recovery efforts of people all across the Island that I could enjoy the scenery from the train that day.

Ah, Taiwan!

I felt in awe of the resilience and vitality that coursed through this formidable colony.

“The damaged Gyotōhei Bridge is located between Jyūroppun Station and Taian Station, and used to be known as the Artistic Treasure of the Taiwan Railroad. Nowadays, you can see the remains of the old bridge when taking the train south from Jyūroppun Station. Perhaps Aoyama-sensei missed it because you did not know to look for it.”

“Jyūroppun, you say? I really must have missed it, then! Next time, I’ll be sure to pay attention.”

From north to south, the Taichū Line consisted of Chikunan, Yokoe, Zōkyō, Hokusei, Byōritsu, Nansei, Dōra, Mitsumata, Jyūroppun, Taian, Kōri, Toyohara, Tanshi, and finally Taichū. My pencil scratched away while my brain whirred. When I first took the train down to Taichū in May, I hadn’t bought a bento at Byōritsu Station and instead had two plain onigiri; when I was passing Jyūroppun Station, I would have just gotten started on the five salted duck eggs. Ah—no doubt I’d missed the ruined bridge while I was peeling the eggshells.

Speaking of which, is there something good to eat around here?

This was the inner dialogue I’d arrived at right before Chi-chan voiced my thought out loud.

And now I was stuffing a handful of freshly shelled fava beans into my mouth.

The deep-fried beans were exquisite in texture as well as taste. The thicker ones were airy and crumbly, the thinner ones crisp with a satisfying crunch; the garlic was quite simply addictive. I was worried about eating too quickly, being two handfuls in and already craving a third. It wasn’t embarrassment for myself that concerned me, but the fact that Chi-chan, who’d been shelling the beans, did not seem to have eaten a single one.

Alas, the fava beans proved to be the collapsed bridge that disrupted the railway of my professionalism.

“Aoyama-sensei?”

“Huh? Oh, yes. Please continue!”

“The Chikunan and Byōritsu region is known for its Hakka population. The local cuisine and language are very different from here in Taichū. But it might be too early to go into specifics— perhaps I should save the explanations for when we visit in the future.”

“Yes, please!”

Chi-chan could be as electrifying as she could be caring. She now nudged a small plate of shelled beans toward me, and I gratefully took my third handful.

Hm? Hold on a second.

“Chizuru-san, you spoke of the Hakka population just now. Do you mean the Mountain Peoples? Come to think of it, after my train passed Byōritsu, I felt like I started to hear different types of Islander dialects. I couldn’t understand any of them, of course, but it sounded to me like they were different from what the young man at the fruit stand was speaking.”

“Aoyama-sensei really is very attuned to linguistic differences. It must be because you grew up among so many foreigners in Nagasaki,” Chi-chan said, continuing to shell fried beans. “In Taichū, the Islanders speak what we call Taiwanese. The Hakka people speak the Hakka dialect, and they refer to the people who speak Taiwanese as Hoklo people and sometimes refer to Taiwanese as the Hoklo dialect, or Hokkien. The indigenous peoples are distinct from both and generally divided into Mountain Peoples and Plains Peoples, but they are in fact composed of many tribes, and each tribe has its own traditions, language, and culture. There are the Tayal and Vonum tribes, for example. In fact, designations such as Mountain Peoples, Plains Peoples, and the umbrella term Bannin are all inaccurate, and there are now some scholars who only refer to these tribes by their original names.”

“I see! So Taiwanese doesn’t actually refer to the aboriginal languages.”

“No. Even before the Japanese Empire received Taiwan, the majority of the population here has been Han people, who are originally from Shina and speak Hokkien. So their dialect has long been referred to as Taiwanese.”

“In that case, which ethnic group do you belong to, Chizuru-san?”

Chi-chan’s hands stopped. She raised her face and gazed at me quietly. “What a trick question, Aoyama-sensei.”

“Hm? Why do you say that?”

“We are all the children of the Heavenly Sovereign. As one family across the seas, there is no division of race—”

I raised my hand to stop her. “Sorry. My mistake. I won’t pry any further.”

Chi-chan smiled and relaxed her voice. “The Ō family is Hoklo. Specifically, we are Hoklo people from the Zhāngzhōu region in Fújiàn in Shina. In Hokkien, our name is pronounced not Ō but Ông.”

“Huh . . . it’s all so complicated . . .”

“Anshi said, ‘A hundred li’s distance breeds different habits, a thousand li’s distance breeds different ways of life.’ It is not because of such differences and complications that Aoyama-sensei needs an interpreter like myself?”

She managed to quote the ancient philosopher with a perfectly natural expression.

I crushed my fourth handful of fava beans with my molars and released the tension in my shoulders. “I see now that one mustn’t underestimate the Island’s public education. The erudition of one schoolteacher alone is enough to leave me speechless!”

It was Plum Rain season in Taiwan. The downpour deluged the green willows outside my window; the teeming river coursed day and night.

The rain and roiling river made for a water song that, in the dark of night, pierced through the earthen roof tiles and wooden awning to serenade me in bed. Several times, on the verge of sinking into a dream, I thought about how this music of rain would surely become one of my vivid memories of Taiwan.

In June, I bade farewell to the Takada mansion in Muhō and moved into a Japanese-style cottage next to the Yana River in Kawabata District of Taichū City.

We called it “the cottage” not because it was small, but because it was the smallest among the many houses owned by the Takadas. Madame Takada had shown me several two-story, Western-style houses, but each time I’d felt that they were too large and luxurious for my needs. Eventually, she brought me to this one-story, Japanese-style abode, explaining, “Kawabata District was only developed recently and is still considered a fringe neighborhood in Taichū. Look at all the paddies! How could we let you stay at a place like this? One positive is that the house is new and well built. My son is the only one who comes sometimes when he is visiting Taichū—usually just for a short break and not to spend the night. But it occurred to us that maybe Chizuko-sensei would actually prefer the quiet. Well, what do you think?”

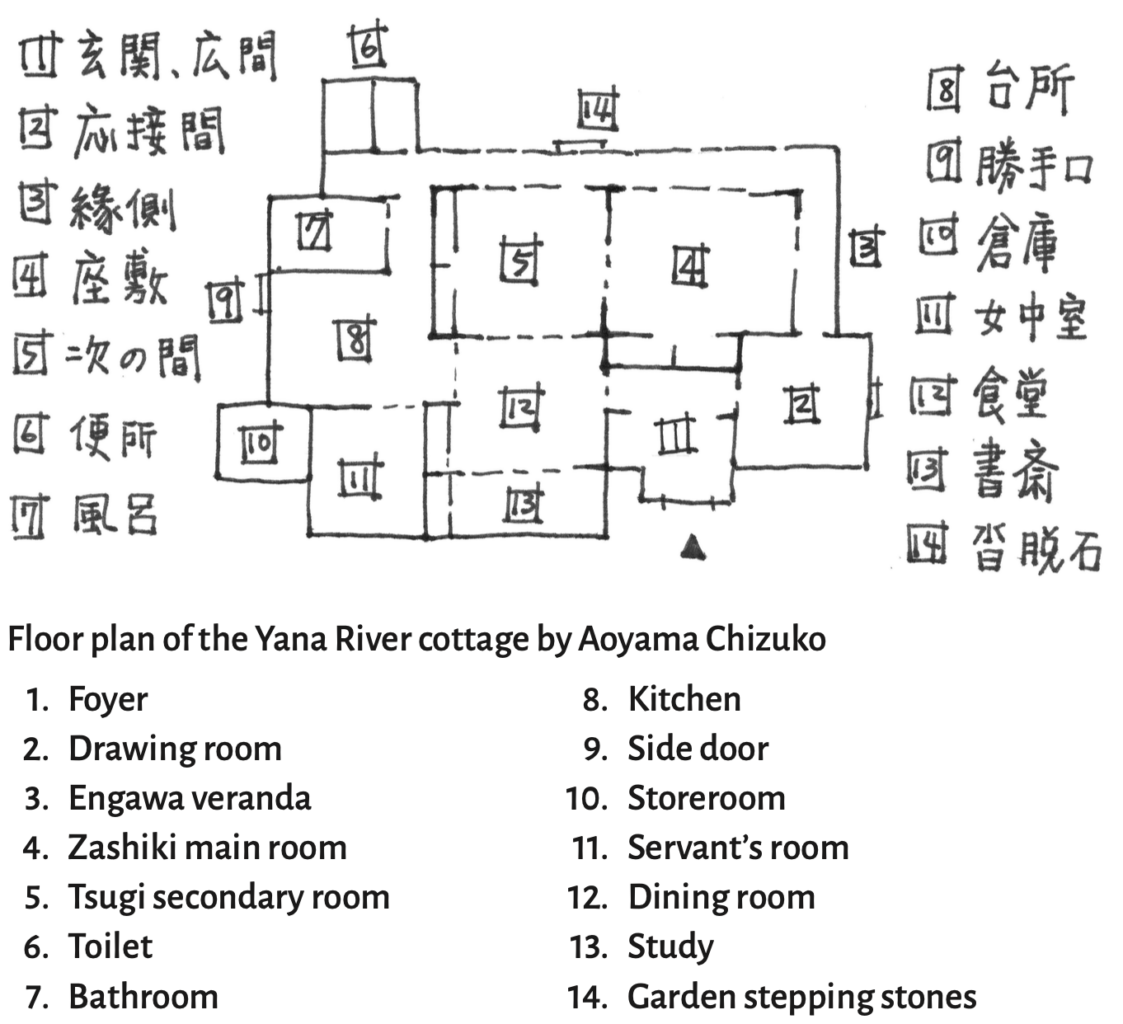

The entrance to the southeast of the house led to a four-tatami foyer; to its right was a Western-style drawing room, to its left a Western-style dining room. The earthen-floored kitchen was eight tatami in size. The study was four tatami, the servant’s room six tatami, and the zashiki main room was, impressively, ten tatami. The secondary tsugi room was, like the kitchen, eight tatami. The bathroom was equipped with a full tub and a traditional Japanese toilet as well as a Western toilet. The engawa veranda ran along the house’s north and northeast, with excellent natural light and ventilation; it looked out into a garden of magnolia trees, sweet osmanthus trees, and a hedge of golden dewdrop shrubs.

In short, it was compact but perfectly comprehensive. “This is beyond ideal, Madame Takada!”

A resounding laugh rang out from her ample body. “The Takada family has always prided itself on being good hosts.”

A true descendant of the Satsuma aristocracy, Madame Takada was quick with her promises and true to her word. She announced that I was to have the house free of charge for the duration of my stay. I returned her generosity of spirit by accepting the offer as resolutely as she proposed it.

“I’ll take it!”

Madame Takada’s smile was so wide that her plush cheeks squeezed her eyes into crescent moons. “With this disposition, Chizuko-sensei will no doubt be somebody of great importance one day.”

Even if she was being sarcastic, I could only accept the compliment.

After I moved into the cottage on the eighth of June, Chi-chan began coming over twice a week. Before I knew it, she’d fully equipped me for my new life: lightweight dresses and hats befitting Taiwan’s climate; leather oxfords and wooden geta; parasols for sun and umbrellas for rain; mackintosh coats that accommodate my stature; brand-new mosquito nets and lightweight summer blankets. The Takada family had arranged for staff to assist me with such things, and such tasks were not within the purview of an interpreter’s job description, but meticulous Chi-chan put everything in order herself. This included securing me a library card at the Prefecture Library, maps of the city and its bus routes, and a list of restaurants suited to dining alone. Everything was done before I could even think of asking for it.

“Chizuru-san is beyond competent—you are omnipotent!”

“Aoyama-sensei exaggerates.”

“No no, I really mean it!” I raised my voice to convey my sincerity. “Not only are these fava beans shelled to perfection, even the tea you make tastes better than other tea!”

“I cannot take credit for that—it’s just that the tea leaves here are superior,” she protested, furrowing her brows.

Ah—so she had this expression up her sleeve, not only the imperturbable smile!

Perhaps because of her childlike face, Chi-chan looked sweet-tempered even when she was frowning. She was wearing a nondescript Western dress of a muted color, but even this office-worker attire could not dim her glow.

Earlier that day, she’d arrived at the cottage with a bag of garlic fava beans and patiently answered my various questions. We left at 10:30 for the local girls’ high school, where I was to speak on my usual topic, “A Record of Youth and Me.”

This was Chi-chan’s first time accompanying me to a lecture. In the preparation phase, I’d protested that a two-hour lecture was far too long. When she’d proposed two class periods instead, I’d replied childishly—as though making one of my appeals to my aunt Kikuko or Haruno—Aw, wouldn’t one hour be plenty? Chi-chan had smiled, shook her head, and said she would try to convince the school. Later, we managed to settle on a lecture that was one class period.

One class period—the last before lunch. I felt hungry already.

The taxi pulled up to the gate of the school and we proceeded on foot, kicking at the rain as we walked.

“Chizuru-san must be pleased to return. This is your alma mater, is it not?”

“It is. Yes, I suppose I should be pleased.” “Are you—not?”

“Well, I have only been gone for three or so years.”

It was then that I noticed something unusual in her smile.

A row of six people awaited us at the school’s door. We changed into indoor slippers in the midst of small talk, and the principal began leading the way while the others surrounded me. “Oi, Ō-san,” came a clipped, low voice from the shoe cupboards behind us. “You’re the personal assistant, yes? Then I’ll leave Aoyama-sensei’s shoes for you to clean.”

What?

I stopped walking and turned back. A middle-aged man who hadn’t even ranked high enough to introduce himself to me was lording over Chi-chan. “There’s mud here and here, see? You can manage a simple task like this, no?”

The impudence!

I marched over. “Ō-san is my interpreter.”

“Ah! Aoyama-sensei, I . . .”

“Please do not make such unreasonable requests of my interpreter.”

I took Chi-chan by the arm and tugged her close to me. She stumbled a step and looked up at me with the same curious smile that I’d spotted before we entered.

My chest ballooned with rage. It felt like a sealed barn of burning hay. I had not been this upset since arriving in Taiwan— not even Mishima’s bureaucratic manners had roused so much distaste.

When the school bell sounded for lunch, I declined the school’s invitation and, without so much as asking for a taxi, stormed out with Chi-chan’s wrist in my hand. When we reached the exit and saw the continuing rain, I stomped back to ask for an umbrella but insisted on leaving again immediately.

“Are you not angry, Chizuru-san? If someone had insulted me that way, I would have smacked his face with the shoe!”

“That does sound like something Aoyama-sensei would do.” “The nerve of the man! I can’t believe it! Ah—you know what the best cure for anger is? Food! Is there something good to eat around here?”

Hehe. Chi-chan’s chuckle rang out as clearly as ever.

“Let us go to Shintomichō Market. Aoyama-sensei enjoys sashimi, yes?”

Emboldened by my anger, I declared, “I can eat a whole tuna by myself right now!”

“I look forward to witnessing it.”

Chi-chan seemed at ease, looking more amused by my reaction than displeased by what had occurred. Meanwhile, I charged forward as though I could tear through the curtain of rain. I didn’t, couldn’t understand: Why did Chi-chan have to suffer this kind of treatment?

__________________________________

From Taiwan Travelogue by Yáng Shuang-zi (translated by Lin King). Used with permission of the publisher, Graywolf Press. Translation copyright © 2024 by Lin King.