The Annotated Nightstand: What Aria Aber Is Reading Now, and Next

“Those people. My whole existence, neatly packed into one demonstrative adjective,” says Nila, the protagonist of Aria Aber’s pulsing debut novel Good Girl. Nila was born in Berlin, “inside its ghetto-heart, as a small, wide-eyed rat, in the months after reunification.” As these quotations show, Nila is whip-smart and undeniably witty.

Yet she is riven with self-hatred. Nila’s parents, Kabul petit bourgeoise and trained as doctors, fled the Soviet-Afghan War with hopes of a better life in Europe. Instead, they were consigned to a world largely defined by xenophobia, violence, humiliation, and menial work—the quotidian but no less degrading reality of so many in their circumstances.

Nila grows up in the particular anxiety of living in Germany post-9/11, when its white populace defines her as a Muslim outsider: “those people.” Nila quickly learns to invent other places of family origin as a shield. “[W]e learned to resent ourselves with precision,” she says of herself and other kids like her.

Nila’s parents’ hopes for her are that she will be educated, informed, “liberated”—yet still tethered to their social mores largely defined by anxiety for her purity and maintaining their good name. Nila fights this tooth and nail. Eventually, “I let the glittery, destructive underworld of Berlin sink its fangs into me,” Aber writes.

At nineteen, Nila’s drug-fueled nights at the techno club Berghain (“the Bunker”) have her fall in with a set of artistic bohemians who reject convention and capitalism through techno, drugs, art, and knowledge. Yet she feels apart from this group considering her life in a building largely populated with other poor refugees and immigrants, its halls haunted by neo-Nazis.

But the most compelling Bunker meeting for Nila is Marlowe, his name a Faustian wink. An “it boy” American writer almost two decades her senior, Marlowe engages Nila in meaningful philosophical conversations on art and life over endless cigarettes and bumps of speed. He also uses aesthetics simultaneously as permission for his behavior and a dodge from meaningful self-reflection, bears copious tattoos so he can’t “sell out” yet covers them easily for a fancy party.

Marlowe tortures Nila by initially delaying her galloping desire (before more explicit tortures), patronizes her for her lack of experience, yet also tells her she’s special. In a sense, he is her parents’ (and this reader’s!) nightmare. At one point, when Nila was younger, her father, desperate to protect her, wants to send Nila away for school. Her mother resists. “‘The world breaks girls everywhere,’ my mother hissed. ‘It’s too late.’” The truth of this proclamation feels impossible to deny.

I feel like these descriptions give the narrative neatly when Aber deftly fights clean chronology. We flip between Nila’s life of Marlowe and drugs and photography and literature outside the walls of her suffocating family apartment—to family memories, her childhood room, and judging eyes everywhere.

While this jockeying (and Aber’s crackling language) makes for compelling reading, in Good Girl it does more. It illustrates the ways in which Nila’s world is divided in two, her terror at the prospect of that barrier thinning palpable.

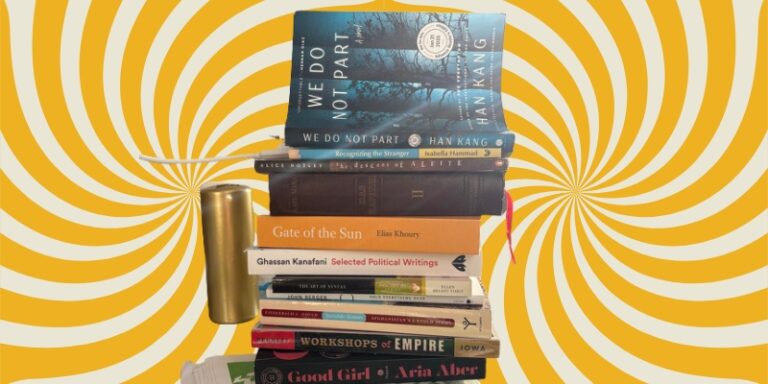

On her to-read pile, Aber tells us,

I just moved with one tote bag of books to a new place, so my nightstand also functions as my library for a few weeks. My own book is embarrassingly part of my stack because I have to re-read it right now—I translated it into German and purged all memory of my own words from my mind; now I’m re-entering it before publication.

But mostly, I’ve been reading a lot of history books and non-fiction to research my next project, so almost everything else, except a few titles, is for that purpose. And of course, I have to say, the Vol. 2 of Marx always goes over my head with those equations…but I need some of it for research, and it’s probably the best bedtime book in terms of putting me to sleep.

*

Han Kang, We Do Not Part (trans. e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris)

Kang won the recent Nobel Prize in Literature and also rejected holding a celebratory press conference because of “the wars raging between Russia and Ukraine, Israel and Palestine, with deaths being reported every day.” Ellen Mattson of the Swedish Academy said of We Do Not Part,

the snow creates a space where a meeting can take place between the living and the dead, and those floating in between who are yet to decide which category they belong to. The entire novel is played out within a snowstorm where, in piecing together her memories, the narrative self glides through layers of time, interacting with the shadows of the dead and learning from their knowledge—because ultimately it is always about knowledge and seeking out the truth, unbearable though it may be….Forgetting is never the goal.

Isabella Hammad, Recognizing the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative

I’m relieved to have the opportunity to quote Hammad from her interview with David Naimon on Between the Covers, as the episode came out *after* her contribution to this column. In her conversation on Recognizing the Stranger, Hammad says of the genocide in Palestine and elsewhere,

I think it’s quite helpful to talk about denialism as a phenomenon, which is a denialism not only about Palestine, but about structures of empire and genocidal histories which are not acknowledged. I mean, Germany committed more than one genocide. What about Namibia? These things haven’t been acknowledged in the Court of Justice and there’s been no compensation, there’s been no retribution.

There’s an ongoing denial about these histories, which are now coming to the surface. We’re seeing the tip of the iceberg, but there’s a huge mass underneath. There’s no wonder that people are in denial because to confront that reality is to confront many things that structure their lives and structure their societies. That’s really scary.

Alice Notley, The Descent of Alette

Using Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces along with the stories of Inanna and others as a map, Notley penned this trippy, mystical, mythical epic poem. Alette, a woman who lives in a dystopic world, is consigned to endlessly ride a subway, run by “the tyrant.” One day, Alette is charged by a stranger to tap into her power and kill their world’s villain.

Notley wrote the poem in the aftermath of her brother’s death. He died from a drug overdose a decade after serving in the American-Vietnam War, where he was forced to exact terrible violence and emerged deeply traumatized. Discussing her brother’s death in her lecture on Alette called “The ‘Feminine’ Epic,” Notley states:

Suddenly I, and more than myself, my sister-in-law and my mother, were being used, mangled, by forces which produce epic, and we had no say in the matter, never had, and worse had no story ourselves. We hadn’t acted. We hadn’t gone to war. We certainly hadn’t been “at court” (in the regal sense), weren’t involved in governmental power structures, didn’t have voices which participated in public political discussion. We got to suffer, but without trajectory.

Karl Marx, Das Kapital: II

I don’t know that I’m going to bring some fresh insight or information on Marx or these texts, but I’m happy to quote Slavoj Žižek’s Objective Fictions on the second volume of this vital work: “Capital, Volume One articulates the abstract-universal matrix (concept) of capital; Capital, Volume Two shifts to particularity, to the actual life of capital in all its contingent complexity.”

Žižek continues,

Two features are crucial here, which are the two sides of the same coin. On the one hand, Marx passes from the pure notional structure of capital’s reproduction (described in Volume One) to reality, in which the capital’s reproduction involves temporal gaps, dead time, etc. There are dead times that interrupt smooth repro-duction, and the ultimate cause of these dead times is that we are not dealing with a single reproductive cycle, but with an intertwinement of multiple circles of reproduction which are never fully coordinated.

Elias Khoury, Gate of the Sun (trans. Humphrey Davies)

In her 2006 New York Times review of Khoury’s novel, Lorraine Adams begins, “To Americans…interest in Arab literature, even after Naguib Mahfouz’s Nobel Prize in 1988, hasn’t moved too far past Aladdin and Sinbad.” Depressingly, it’s hard to know if this has changed in the almost twenty years since her proclamation.

Adams continues:

[W]hile Khoury’s narrator explores Palestinian privation and Israeli cruelty, this is not a predictable novel of despair and accusation… There has been powerful fiction about Palestinians and by Palestinians, but few have held to the light the myths, tales and rumors of both Israel and the Arabs with such discerning compassion. In Humphrey Davies’ sparely poetic translation, Gate of the Sun is an imposingly rich and realistic novel, a genuine masterwork.

Ghassan Kanafani, Louis Brehony (editor), Tahrir Hamdi (editor), Selected Political Writings

“For Kanafani, resistance was the essence of everything he wrote as well as the life he led as a revolutionary thinker who fought for Palestinian liberation with his pen,” writes Benay Blend in her review for The Palestine Chronicle.

The book is organized according to prominent themes in the writer’s work—Kanafani and the media, building the Marxist-Leninist Front, and Arab nationalism and socialism, to name a few….This collection of Kanafani’s writing provides invaluable material for political education. As repression increases against diasporic Palestinians and their supporters, it’s important to know this history. Only then can a solid defense be built against those who are intent on silencing organizing around Palestine forever.

Ellen Bryant Voigt, The Art of Syntax: Rhythm of Thought, Rhythm of Song

Voigt’s The Art of Syntax is part of Graywolf’s The Art Of series in which authors meditate on artistic practices and includes Edwidge Danticat’s The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story and Peter Ho Davies’ The Art of Revision. Michael Morse writes of Voigt’s work in Ploughshares,

Highlighting common syntactical patterns and their musical arrangement, exploring how poetic lines interact with sentences, and illustrating how phrasing can balance or undermine meter, relax or propel pacing, and score unfolding narratives, Voigt reveals a detailed topography of conjoined music and meaning…Voigt’s larger concerns with poetic evolution out of structural wellsprings allows for a variety of aesthetics as poets swim with, against, and inside the syntactical currents of English.

John Berger, Hold Everything Dear: Dispatches on Survival and Resistance

With The Ways of Seeing, Berger seemed to change the aesthetic dialog by pushing back on Western conventions of aesthetics (we have him to thank for introducing the concept of the male gaze, even if it had been executed for millennia). The jacket copy for Berger’s Hold Everything Dear states,

A powerful meditation on political resistance and the global search for justice. From the ‘War on Terror’ to resistance in Ramallah and traumatic dislocation in the Middle East, Berger explores the uses of art as an instrument of political resistance.

Visceral and passionate, Hold Everything Dear is a profound meditation on the far extremes of human behavior, and the underlying despair. Looking at Afghanistan, Palestine and Iraq, he makes an impassioned attack on the poverty and loss of freedom at the heart of such unnecessary suffering. These essays offer reflections on the political at the core of artistic expression and at the center of human existence itself.

Elizabeth Gould, Paul Fitzgerald, Invisible History: Afghanistan’s Untold Story

Publishers Weekly in its 2008 starred review for Invisible History writes,

Journalists Fitzgerald and Gould do yeoman’s labor in clearing the fog and laying bare American failures in Afghanistan in this deeply researched, cogently argued and enormously important book. The authors demonstrate how closely American actions are tied to past miscalculations—and how U.S. policy has placed Afghans and Americans in grave danger.

Long at cultural crossroads, Afghanistan’s location poised the country to serve as “a fragile buffer” between rival empires. Great Britain’s 1947 creation of an arbitrary and indefensible border between Afghanistan and the newly minted Pakistan “from the Afghan point of view…has always been the problem,” but particularly after 9/11 American policymakers have paid scant attention to the concerns of Afghans, preferring to shoehorn an imagined Afghanistan into U.S. power paradigms.

Eric Bennett, Workshops of Empire: Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing During the Cold War

“In Workshops, Bennett demonstrates how the aesthetic dominance of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, run by Paul Engle, and the creative writing program at Stanford, run by Wallace Stegner, were specific products of their place and time: the U.S. in the 1950s,” writes Rebecca Weaver in Rain Taxi.

The programs were not only funded and supported by various policies and agencies of the government (such as the GI Bill and the CIA and UNESCO), but also by private foundations (notably the Rockefeller Foundation)….While many have attributed words such as “natural” and “quality” to the phenomenon of Iowa’s eminence and dominance, Bennett argues that the type of writing valued at Iowa (and the programs established by its alums) grew out of specific goals and desires, as well as “ambitions and weird fears,” associated with the Cold War.

When those goals dovetailed with governmental or philanthropic goals, they were funded quite well.