The Annotated Nightstand: What Mónica de la Torre Is Reading Now, and Next

An early poem in the translator and poet Mónica de la Torre’s latest volume Pause the Document begins with: “trees, pillars in nature’s temple, speaking / vague, perplexing words.” She is referencing the first two lines of Charles Baudelaire’s “Correspondences,” which begins (as translated into English by Ariana Reines): “Nature is a temple where living pillars / Sometimes let out confused lyrics.” “Confused lyrics” is originally “confuses paroles.”

De la Torre continues in her poem, “confuses paroles easily becomes palabras confuses.” She then, with a sharp yet expansive translator’s mind, spins out on words’ meanings and those adjacent, from “palabra” to “parabola,” “confused” and “confound.” This poem is dedicated to Caroline Bergvall who, in her piece “Via”, shows the varieties of approaches to the first two lines of Dante’s Inferno.

De la Torre, too, is fixating on two lines, in this case by the Symbolist poet famous for writing about urban scenes, infusing images of decay and deviance with beauty. De la Torre’s poem, entitled “Parable,” ends with a scene of the speaker as a child alone on a grim playground. She hears the rustling of trees.

“They speak to her for the first time,” De la Torre writes, “yet she can’t put what they say into any of the words she knows.” In Baudelaire’s poem, he continues, “Man passes through, across forests of symbols / Each one observing him with a familiar gaze.”

I’ve meditated on this single poem for so long—and I didn’t even get to Saussure and semiotics!—because it’s clear De la Torre is setting the scene for the remainder of the book. It shows us the ways in which she looks at world—especially how we engage with one another (humans, trees, what have you) through “confuses paroles.”

Few periods of time seemed more apt for this description than the height of the pandemic, when time bent for so many of us it felt like it would snap (not to mention our minds or spirits). Throughout the poems that are in a variety of shapes and modes, De la Torre chronicles a series of moments from this period. Through our shared vulnerability of that period, the quotidian can be flush with meaning, as when the speaker sees a latex glove on the ground,

Signaling to a passersby,

left behind, discarded….Speaking,

gestures of waste, how we protect

ourselves.

Claudia Rankine says of Pause the Document, “Rebounding their kaleidoscopic thinking and consciousness off the surfaces and textures of the landscape, the brilliant poems of Pause the Document remind us how we can ‘unfold as a flow’ inside language and life.”

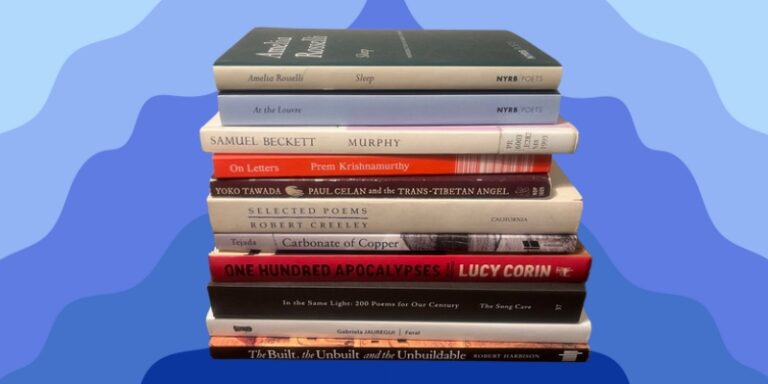

De la Torre tells us about her to-read pile,

Books I should’ve read by now, books I haven’t gotten to, friends’ newish books, books bought impulsively, books I’m in, books I want to read as slowly as possible, books I ought to read asap for class or a writing project, stacked up as if awaiting that chance moment at which I can no longer put them down and commit to them. They guard my sleep, prolong the dream.

*

Amelia Rosselli, Sleep

The jacket copy for Sleep, from NYRB, states,

Amelia Rosselli is one of the great poets of postwar Italy. She was also a musician and musicologist, close to John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and she waged a lifelong battle against depression….The elaborate, archaic, yet thoroughly modern poems, at once stumbling and singing, that Rosselli composed in English and gathered under the title Sleep are a beautiful and illuminating part of her work.

Six of the poems were published by John Ashbery in the 1960s but have otherwise been unavailable to English readers. They are published here for the first time outside of Italy.

Antoine Caro (editor), Edwin Frank (editor), Donatien Grau (editor), At the Louvre: Poems by 100 Contemporary World Poets

Walker Mimms named this one of “The Best Arts Books of 2024” at the New York Times (I love that they show John Keene’s poem there). Mimms writes,

At its best, poetry about art, or ekphrasis if you like, makes visual recognition audible. This portrait of the largest museum in the world, by a motley and reaching group of living poets, goes a step further, capturing not just the hidden comedy of the sculptor Pierre Puget’s ancien régime “Hercules at Rest” (see Simon Armitage’s contribution) or the sadness in Jean-Antoine Watteau’s “Embarkation to Cythera” (see Istvan Kemeny’s), but also all the happenstance, ritual, baggage and reverence that comes with tracking down artworks in an actual building.

Worth the volume’s modest price are Jay Bernard’s associations from streetside to neoclassical gallery, the overload of Elizabeth Willis’s breakneck couplets, and an unlikely stereotype: Even poets flock to the Mona Lisa.

Samuel Beckett, Murphy

I’ll be the first to admit I am *very* suspicious of “best ### novels”—with “ever” being implied at the end. But! I’m still curious what different writers, thinkers, and editors consider their top books. Robert McCrum writes of Murphy, (number 61 in “100 best novels” at The Guardian),

The workshy eponymous hero, a “seedy solipsist,” adrift in the alienating metropolis, realises that his desires can never be fulfilled conventionally. He withdraws from life in search of a personal stupor. When the novel opens, Murphy has tied himself to the rocking chair in his flat with seven scarves and is rocking to and fro in the darkness.

This practice, apparently habitual, has become Murphy’s way of achieving an existential state of being that gives him deep private satisfaction. Even his lover, Celia, cannot lure him back into the world….Murphy is a showcase for Beckett’s uniquely comic voice, his command of absurdist narrative, and fascination with existential, mind-body issues of being and nothingness.

Prem Krishnamurthy, On Letters (Red Version)

Krishnamurthy is a designer and author whose book On Letters is a wild design-forward engagement with the artist On Kawara’s Today series (aka “Date Paintings”). The Guggenheim website describes the Today series as a half-century project. “A Date Painting is a monochromatic canvas of red, blue, or gray with the date on which it was made inscribed in white.”

Just breaking in here to say Krishnamurthy’s book was printed in red, blue, or gray.

[Kawara] did not create a painting every day, but some days he made two, even three. The paintings were produced meticulously over the course of many hours according to a series of steps that never varied. If a painting was not finished by midnight, he destroyed it. The quasi-mechanical element of his routine makes the production of each painting an exercise in meditation….The series speaks to the idea that the calendar is a human construct, and that quantifications of time are shaped by cultural contexts and personal experiences.

Yoko Tawada, Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel (trans. Susan Bernofsky)

John Domini writes of Tawada’s novel at The Brooklyn Rail,

The main character starts out as ‘the patient,’ isolated and struggling with OCD, hardly able to get around his home blocks in Berlin, but over time he transforms into “Patrik,” more sociable and spirited. On top of that, whether patient or Patrik, he slips at times into first person: a narrator. And whatever his guise, it allows Tawada a fresh opportunity for linguistic play—the wit that distinguishes all her work—as well as insights that aren’t solely playful.

And, when Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel “reaches climax—as its protagonist starts to revive—the text meditates on how the young Celan, amid the terrors of the camps, used the imagination to comfort himself: ‘Sorcerers, witches, and monsters will protect the sleeper from the nightmare of genocide.’”

Robert Creeley, Selected Poems

Gotta love an old review. This is from Publishers Weekly in 1991 for this collection,

Creeley, poet laureate of New York State, constantly gauges what it means to be human, in poems that cope with the rush of memories, the chaos of dreams, the sudden flare of feelings. His mercurial verses on love and life’s vicissitudes respond instinctively to our innate but half-articulated need for roots, familial, social and spiritual. There is a deep strain of pessimism in a poet who proclaims ‘both men and women cold / hold at last to no one / die alone.” From the pared-down, pure diction of “For Love” to the recent complex thought-experiments of “Memory Gardens” and “Windows,” this gathering of two hundred poems charts the trajectory of a poet who delights in words and remains true to self.

Roberto Tejada, Carbonate of Copper

The editors and staff at Chicago Review published two poems from this collection, along with this note:

Time is slowed and sedimented in these poems by Roberto Tejada: people and environments are weathered, eroded, or worn down, outwardly placid but existing in a kind of insubordination….But if time is a process of weathering, it is also the condition for apparition—the coming into perception of a view that may fade.

When a landscape “obtains” in “Carbonate of Copper,” it projects a wholeness on things in order to consume them, things the poem’s spacing renders separate and out-of-sync. This oasis or mirage highlights temporalities otherwise out of joint, as the poem switches between layers of history, community, industrial and domestic labor.

Lucy Corin, One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses

In an interview with J.B. Powell at The Rumpus, Corin says of One Hundred Apocalypses,

so many of the stories are about perspective and viewpoint. It’s not just about seeing and revelation. The idea of having many different stories from many different perspectives has something to do with me trying to deal with the impossibility of having a wide enough view to say anything really convincing on that scale. A lot of times when I ask people what their apocalyptic fantasy life is like, they’ll immediately say something like, “Oh, what I think is going to kill us is climate change or World War IV,” and that’s not what I’m interested in at all. The point is not about winning a bet about what’s going to happen. The point is about the human action of examining the possibility, the kind of obsessive imagining about it.

In the Same Light: 200 Poems for Our Century (trans. Wong May)

Noah Warren at Astra Magazine (RIP) writes,

Wong May (b. 1944), a global writer of Chinese origin, returns to the Tang canon not as to a treasury, but as to a vintage store, rummaging for what fits now and walking out with it. In her radical translations, the gridded five-or seven-character lines of Du Fu, Li Bai, and their fellow bureaucrat-poets, splinter into poignancies jotted down in flight or captivity; her free renderings return motion and breath to these artifacts that have stiffened into sepia and landscape.

Furthermore, the thrilling, spidery translations are only half the show: the heart of the book lies in its ninety-seven-page, shape-shifting afterword, where Wong and a magical rhinoceros, who sounds suspiciously like her classical Chinese poetry-writing mother, enter the Tang chat. Wong and the rhino function as impresario-interlocutors, plucking at questions about poetry’s imbrication with Chinese society in the eighth and twentieth centuries, chatting familiarly with Ezra and Emily (Dickinson), and painting in vivid strokes the misery of the An Lushan rebellion (755-763 CE).

Gabriela Jauregui, Feral

In Feral, far-future archivists sift through the lives of four friends who live on a commune together. One of these friends leaves the commune, traveling to Teotihuacán to work at an archeological site. Those who remain behind soon learn she was murdered. “An audacious and turbulent narrative,” write Fernanda Melchor, Guillermo Arriaga, and Socorro Venegas, the adjudicators of the Latin American First Novel Award.

They go on, “With an intimate and powerful prose, the novel shapes a lush archive that explores the dynamics of solidarity and affection among women, while also confronting the harsh realities of femicide, impunity, and discrimination, among other scourges of contemporary Mexico.”

Robert Harbison, The Built, The Unbuilt, and the Unbuildable: In Pursuit of Architectural Meaning

“The pristine, the ruined, the ephemeral, and even the notional are the subject of Robert Harbison’s highly original and admittedly romantic contribution to the literature of architecture,” states this book’s jacket copy,

His fresh perceptions open this practical art to new interpretations as he explores the means by which buildings, real or imagined, evade or surpass functional necessities while sometimes satisfying them. What fascinates Harbison in these discussions are the paradoxes and ironies of function that give rise to meaning, to a psychological impact that may or may not have been intended.

He chooses examples from an architectural borderland—of gardens, monuments, ideal cities and fortification, ruins, paintings, and unbuildable buildings—where use and symbolism overlap.