The Annotated Nightstand: What Pádraig Ó Tuama is Reading Now, and Next

Pádraig Ó Tuama is a person of many admirable hats, including working on peace and reconciliation organizations, and mediation organizations in Ireland. He’s also a public speaker, actively arguing against the abusive “conversion therapy” for queer and gay kids. He is also a podcast host, an event coordinator. He is also a theologian, recently earning his doctorate at the University of Glasgow.

His poetry is awash with all of these pursuits and experiences. Kitchen Hymns, just out from Copper Canyon Press, is no exception. In an interview with Sam Louis Spencer at Write or Die, Ó Tuama explains the title “is a phrase from Ireland for the hymns that were sung at home in the kitchen, rather than the chapel, because they weren’t in Latin, they were in Irish…[Things that don’t] find their home in the places of religion, but find their home in the places of domesticity.”

What on its face may seem like a direct crisis of faith (there are many poems entitled “Do You Believe in God?”), Ó Tuama instead is investigating the reality of the nothing God inhabits, while not equating it with a void. One poem is a conversation in which someone baldly states, “I don’t believe in God,” but later gives this dimension: “the burden / of belief isn’t on me anymore.”

It’s an aim to meet the nothingness of God rather than what we humans try to stuff in that nothing out of anxiety of its existence.

This while growing up and living in a place defined by ritual and faith. Beneath the series of “Do You Believe in God?” poems, we go through pieces of Ó Tuama as a child spending time with family and the dark realities there, or experiencing desire and sex as an adult. One longer poem tells of Protestant missionaries coming from Northern Ireland to try to convert the Catholics there.

Lonely, Ó Tuama hangs around them. “Do you believe in mass?” a missionary asks on day.

“The question seemed like asking me if I believed in toast, or tea, / or beatings. Plain facts. Are you asking if I like it? I asked. / He doesn’t understand, she said, looking straight through me.”

Ó Tuama includes a long sequence in which Persephone and Jesus. Both consigned to Hades (Persephone as is her perpetual plight, Jesus after his crucifixion), they connect on their way back to the world above. Their lives are of a twinning kind—both with gods for fathers, forced to suffer a dismal fate without their consent.

Their modern personalities shine through, with Persephone aptly putting Jesus into his place (“Christ, you’re such a narcissist.”). Such are the ways in which Ó Tuama probes faith and its invariable stickiness while simultaneously remaining open to its mystical possibilities.

Ó Tuama tells us about his to-read pile,

The Irish language title in this to-be-read pile is a rendition of an old myth where a character—Suibhne—is cursed by a monk and turns into a bird. He flits from place to place, making homes everywhere and nowhere. That’s how I feel sometimes: interested in many topics: poetry, psychoanalysis, conflict, letters, writing, death and belief.

*

Lou Andreas-Salomé, You Alone Are Real to Me: Remembering Rainer Maria Rilke (trans. Angela von der Lippe)

Paula Friedman writes in the 2003 New York Times review of You Alone Are Real to Me:

The critic, essayist and novelist Lou Andreas-Salomé first met Rainer Maria Rilke in the summer of 1897, when she was thirty-six and he twenty-two. Both their age difference and Salomé’s standing as a well-regarded writer helped define their relationship. In the first, passionate years, Rilke often stayed with Andreas-Salomé, traveling twice to her homeland, Russia.

Friedman goes on to say,

[Andreas-Salomé] created a credible and complex portrait of the poet as a man who longed to transcend mortality, often tormented by his own physical existence. Without direct expression of feeling, she conjures the man and his profound importance to her as poet and dear friend in this unusually thoughtful memoir, superbly translated from the German by Angela von der Lippe.

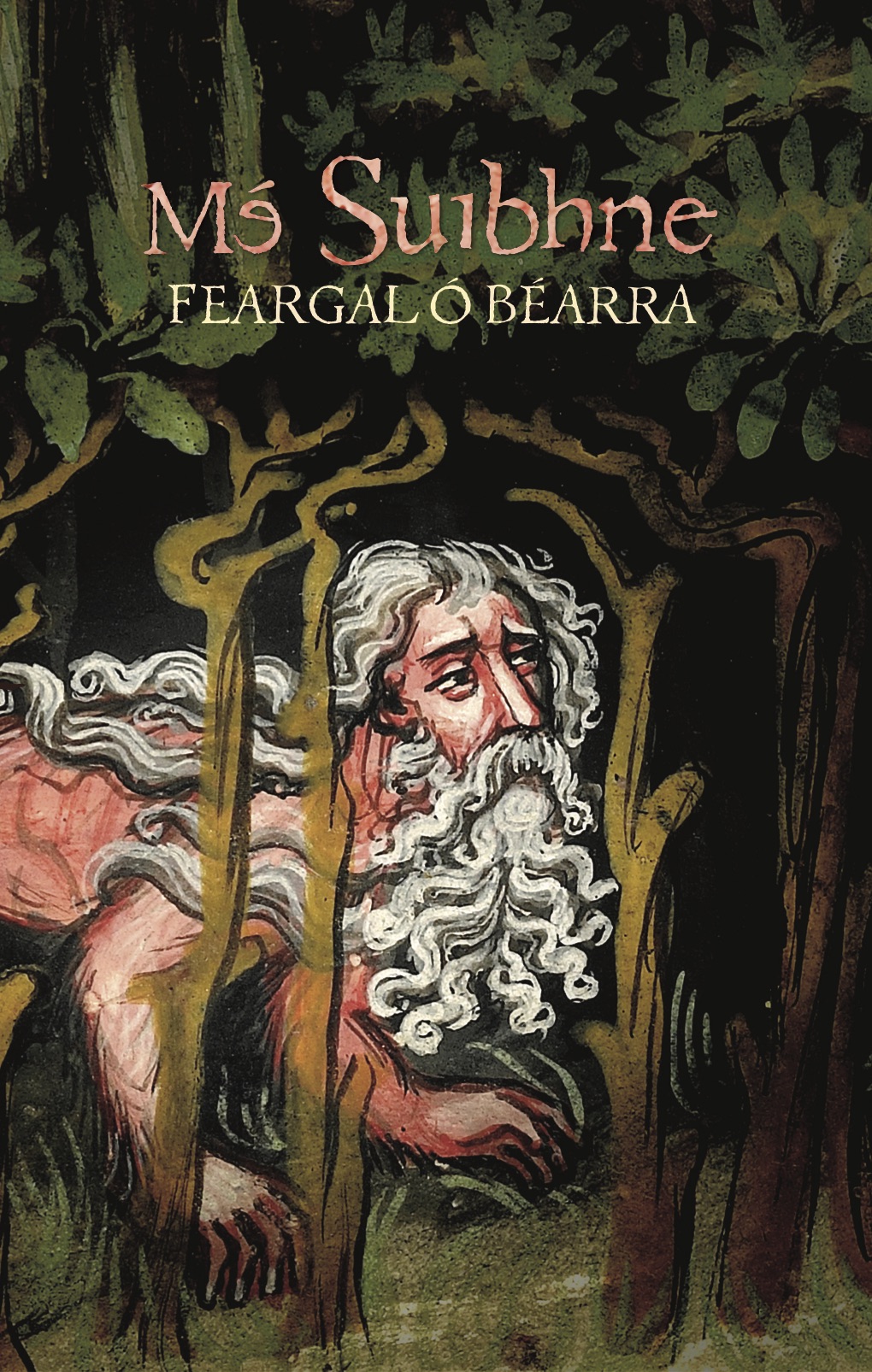

Feargal Ó Béarra, Mé Suibhne

As Ó Tuama says above, Ó Béarra retells the Medieval Irish story Buile Suibhne. In Buile Suibhne, Suibhne earns the ire of a Bishop Rónán (later Saint Rónán) as he’s planning to set up a church in the area. Suibhne attacks the bishop, the former totally naked as his wife tried to stop him from leaving the house by holding onto Suibhne’s cloak—which unraveled as he ran. The bishop curses Suibhne to wander naked and die at the end of a spear.

During another interaction, Suibhne kills a psalmist with a hurled spear of his own and tries to kill the bishop, but fails—earning yet another curse including to wander like a bird. In addition, Suibhne would “Fly through the air like the shaft of his spear and that he might die of a spear cast like the cleric whom he had slain.”

Things get even spicier. Suibhne goes mad, hangs out in trees, eludes captures from people who want to hurt him and who want to help him, wanders around Ireland, Scotland, and England. He is brought back to lucidity, then loses his mind yet again, befriends another man living in the woods for a while.

Ó Béarra’s book is, according to the jacket copy, “a tale about mental illness, about confrontation with the Church, about the tragedy of man.”

Ernst Pfeiffer (editor), Sigmund Freud and Lou Andreas-Salomé Letters (trans. William Robson-Scott)

In the 1975 review of this collection in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, W.C.M. Scott writes,

[Andreas-Salomé] was born in 1861, the daughter of a religious Russian general, but in her early teens she turned away from life to a world of fantasies. Later she sought help from a Swiss pastor who was twenty-five years her senior. He taught her much but eventually spoiled the relationship by proposing marriage.This precipitated illness and she sought a new life in traveling and making friends with a series of notable men. She became especially close to Nietzsche and Rilke. From the age of twenty-six she led an asexual marriage. After a few years in Berlin, she lived with her academic husband in Gottingen until his death.

At the age of 50 (1911) she became enthused by psychoanalysis and spent some time in “conversations” with Freud, and attended meetings of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. From then until the end of her life she actively practiced analysis.

You have to love this final sentence of the review: “It is a very enjoyable book.”

Julie Reshe, Negative Psychoanalysis for the Living Dead: Philosophical Pessimism and the Death Drive

The jacket copy of Reshe’s volume reads,

This book offers a radical alternative to the positive orientation of popular psychology. This positive orientation has been criticized numerous times. However, there has yet to be a coherent alternative proposed.

We all know today that life hurts and that there is no ultimate remedy to this pain. The positive approach feels to us as dishonest and irrelevant. We require a new, more negative, perspective and practice, one that is honest and does not pretend to offer an escape from the agonies of the world.

This book offers in three main chapters a “depressive realist” perspective that explores the structural role of negativity and tragedy in relation to the individual psyche, society, and nature. It explores the possibility of “negative psychoanalysis” which takes into account the tragedy of human existence instead of adopting escapist positions.

Vona Groarke, Woman of Winter

Martina Evans’ review in The Irish Times states that Woman of Winter is Groarke’s

new version of The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare. Responding to the poem’s deep engagement “with how the world is to be experienced through the body…specifically, through the body of a woman whose social standing has been compromised as she has aged,” Groarke extends this “forensic examination” of the ageing body, “now I’m worn thin as threadbare cloth my barebone life pokes through.”

“The Lament of the Old Woman Beare” is a tenth-century Irish Gaelic poem that Eleanor Hull, a folklorist worthy of a Wikipedia wormhole dive, describes thusly: “a beautiful example of the wide-spread idea that human life is ruled by the flow and ebb of the sea-tide, with the turn of which life will dwindle, as with the on-coming tide it waxes to its full powers and energy.”

In her Irish Times review, Evans goes on, “Woman of Winter is as relevant to the twenty-first-century woman as it is true to the spirit of the original lament, its pitiless, richly assonantal voice commanding trust with its honest dissection of a ‘cramped, parched room.’”

Tsitsi Ella Jaji, Beating the Graves

In an interview with Darlington Chibueze Anuonye, Jaji states,

Beating the Graves is the direct translation of the name for a ceremony in Shona culture, kurova guva, which takes place about a year after a person is buried. It is an important rite of transition. I had learned about my ancestral history and the characteristics of my family’s totem from my aunts during a visit home after my grandfather passed away, and that led me to do more research into Shona praise poetry, especially the work of A.C. Hodza, George Fortune, and Alec Pongweni.

The “Ankestral” section of Beating the Graves, and many of the poems based on animal imagery and/or honoring elders, are informed by that research. I’ve written about this principle of relating through poetry in an essay Decolonizing the Poem’ in The Cambridge Companion to the Poem.

The other long section of Beating the Graves, “Carnaval,” is in fact the first poetry I wrote for that book, and it was originally in the program notes I wrote for a set of twenty-four piano pieces by the German composer Robert Schumann that I played in my graduation recital for my music degree.

Each piece was short and distinctive, and I feel that this exploration of classical music is no less African than, say, a VaNyemba poem, because all my writing is filtered through an African moral education.

Rachel Blau DuPlessis, A Long Essay on the Long Poem: Modern and Contemporary Poetics and Practices

In Modernism/Modernity, Henry Weinfield writes of DuPlessis’ recent book,

In this engaging and deeply meditated study, Rachel Blau DuPlessis begins from the premise of the poet’s longing to compose a long poem. “I wanted to understand the fascination of the very long poem, so challenging to readers, yet so compelling for their authors,” she writes.

As this sentence indicates, DuPlessis, herself the author of a long serial poem, Drafts, is fully aware of the divide between readers and writers; nevertheless, her study is boldly focused on poets rather than readers, and (as her subtitle indicates) on poetics rather than poetry itself.

Quotation is kept to a minimum, and, as she acknowledges, the book offers little in the way of close reading. Theory might be said to take the place of language in this study. “The long poem,” she asserts, “is a kind of research, inhabiting poetry as a mode of inquiry.”

Kazim Ali, Black Buffalo Woman: An Introduction to the Poetry & Poetics of Lucille Clifton

If you are not yet initiated into the remarkable poetry of Lucille Clifton, here is a means to fix that (and, while you’re at it, read An Ordinary Woman, at least!). Elizabeth Alexander’s brief New Yorker obituary will give you the necessary details of her life and importance.

When she won the Ruth Lilly Prize, the judges said,

One always feels the looming humaneness around Lucille Clifton’s poems—it is a moral quality that some poets have and some don’t. Her poems are local and funny, and have their own particular idiom; they speak big things in quiet ways, and she’s voracious in the subject matter she takes on, spanning city and country, speaking for the unspoken, the sacred, and the invisible.

Ada Limón says of Ali’s volume on Clifton’s work,

There are few joys as authentic as witnessing one poet praise and honor another. Lucille Clifton is one such poet that deserves all the praise from those of us who attempt to wander in her wake. In Black Buffalo Woman, Kazim Ali allows for not only the elucidation of Clifton’s poems, but for their illumination.

Margaret Atwood, Paper Boat

“Paper Boat unfolds across more than six decades, collecting some of her earliest published work—she began as a poet—and sampling all fourteen of her collections so far,” writes Ali Smith at The Guardian.

The first will never not be near-terrifying and simultaneously strangely freeing in its viscerality, its acid bite. The latter is so moving and expansive about love and loss that out of its wryness, its gravitas and its deep sadness blooms something far beyond the word “moving.” But then Atwood’s work, her poetry in particular, has always asked words—or maybe us—to press beyond any settled expectations.”

Smith goes on to quote Atwood:

“There are always concealed magical forms in poetry,” Atwood said in an interview in the 1970s. “You can take every poem and trace it back to a source in either prayer, curse, charm or incantation.” What a book of magic Paper Boat is, huge but somehow still unassuming, perhaps because of its steady-eyed passage through a history and a life, its open continuance.”

Nicole Sealey, The Ferguson Report: An Erasure

Safiya Sinclair writes here at LitHub on Sealey’s vital book,

In The Ferguson Report: An Erasure, Sealey takes a document that began with death, and re-imagines a space that is ultimately about life and its possibilities. The original Ferguson Report was commissioned by the Department of Justice after Mike Brown was shot to death by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, triggering waves of protests and calls for systemic change against racist policies and police violence.

This collection challenges the cyclical nature of that racial violence. Through erasure, a poetic form traditionally used to carve away at the page in a kind of fixed experiment, Sealey instead blooms something transformative and entirely new.

“They say wait,/ so we wait, as if for some/ fragrant flower that unfurls/ one night a year,” she writes, masterfully re-shaping words from the background of the document, to resonant effect: “They say shh,/ so like trees we mouth cross/ sounds of flags beaten to shreds/ by wind.”