The Annotated Nightstand: What Rosa Alcalá Is Reading Now, and Next

December is the period in which there are the many lists of “great books” published throughout the year. We often see many of the same titles, again and again. As a kind of intervention into this practice, I instead look at a book or books that, for whatever reason, despite their undeniable power, deserve more attention than they have received.

I could have written about so many books I adored that came out this year (Chloe Garcia Roberts’s Fire Eater; Elisa Gabbert’s Any Person Is the Only Self; Insana’s Slashing Sounds tr. by Catherine Theis; Sally Wen Mao’s Ninetails: Nine Tales; Alison C. Rollins’s Black Bell—which I loved so much I reviewed it for LARB).

I’m so glad to be shining a light on the inimitable Rosa Alcalá’s poetry collection that came out earlier this year: YOU. Claudia Rankine’s Citizen illustrated, palpably, the power of second person and its instant placement of the reader into the text and its events. Alcalá demonstrates that power again in YOU.

Here, we read about “you” on her knees begging a lover to take her back. We read about a daughter who learns about Houdini and wants “you,” her mother, to tie her up under a desk and time her escape again and again. (“What are you preparing her for?” Alcalá asks.)

We read a list of advice from “your” mother, which includes cooking tips alongside how to flee or contend with men. As with Joe Brainard’s I Remember, what might at first glance seem bloodless description quickly proves itself to be pulsing with importance. YOU is incantatory, and I was briskly caught in Alcalá’s spell.

These poems powerfully address the knotty realities for mothers, daughters, girlhood, womanhood, and their inheritances: longing, terror, wisdom, kinship, jealousy, desire. In YOU, Alcalá assembles a triptych—herself at its center, her mother and daughter on either side—to present us with a tableau of the potent experiences of womanhood from different angles.

Page after page, her descriptions accrete to a simultaneously poignant and biting investigation of what women endure. In one particularly powerful poem, “How You Became a Poet,” Alcalá describes being a small child and seeing her father harm her mother. “You were invisible but with such big eyes,” she writes. “You were learning not that a woman can’t move up but that she can’t get out.”

Leonora Simonovis writes of Alcalá’s latest collection at the Poetry Foundation, “YOU is a powerful collection that validates past experiences as necessary for growth, and that celebrates the many versions of a self with honesty, humor, and openness.” In the first poem of the volume, the one that isn’t a block prose poem, Alcalá explains how she came, in a “middle-aged body,” to write the book. The purpose of YOU: “to map where fear begins / for girls, for women.”

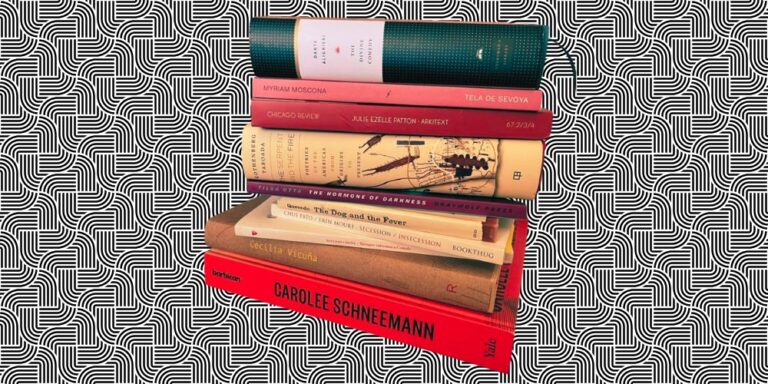

Alcalá tells us about her to-read pile,

My unmanageable piles of books usually consist of the following sometimes-overlapping categories: currently reading, up next, dipping in and out of, given to me on a recent trip, using as reference for what I’m writing, and just-read but not ready to remove from pile. From this pile, I’ve been mainly focused on 1) Moscona’s Tela de sevoya (Onioncloth), translated by Antena (Jen Hofer and J.D. Pluecker), which the author gifted when we read together at an event in Mexico City, and 2) The Divine Comedy (I’m still in hell).

*

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy (trans. Allen Mandelbaum)

I don’t know that I’m going succeed in ferreting out new information on Dante or what we generally call Dante’s Inferno for you all. But one of my favorite Divine Comedy tangents is William Blake’s incredible art for the epic poem. John Linnell, the artist and engraver, commissioned Blake to complete a series to The Divine Comedy, which he unfortunately didn’t finish (he died a year later).

While Blake is known for Songs of Innocence and Experience, his art for The Divine Comedy, as well as Paradise Lost, is some trippy shit. Blake, despite his current fame, died destitute. His wife, the brilliant artist who added color to so many of his engravings, ultimately had to sell some of his copper plates of his engravings to make ends meet, which were likely melted down and put into shoe heels.

Despite his financial dire straits, apparently he spent one of his dwindling shillings on a pencil so he could continue his work on his Dante sketches.

Myriam Moscona, Tela de Sevoya/Onioncloth (trans. Antena [Jen Hofer and JD Pleucker])

Since reading this hybrid book when it came out, I have been absolutely obsessed with it. In its pages, Moscona chases down the Ladino language through family, lore, and dreams. Beyond the book itself, I have such deep respect for Pleucker and Hofer’s work on translating such a wild and compelling text.

In their introduction to the book, Antena writes,

The narrator of Tela de sevoya travels to Bulgaria, searching for traces of her Sephardic heritage. Her journey becomes an autobiographical and imagined exploration of childhood, diaspora, and the possibilities of her family language: Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, the living tongue spoken by descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. Memoir, poetry, storytelling, songs, and dreams are interwoven in this visionary text—this tela or cloth that brings the past to life, if only for a moment, and weaves a powerful immediacy into the present.

You can read an excerpt of Tela de Sevoya in Jewish Currents.

julie ezelle patton, Arkitext: Chicago Review

In their description of this issue devoted to patton’s work, Chicago Review states,

julie ezelle patton is a permaculturist, poet, performer, and artist based in Cleveland, Ohio, and New York City. This issue of Chicago Review, in progress for several years, takes a multi-decade look at patton’s intertwined practices of writing, performing, curating of buildings, ecology, and community. In conversation with approximately one hundred pages of unpublished work by julie ezelle patton are critical essays, responses, and interviews….

Interspersing these works are color photographs documenting “The Building.” The Building [is] a book-building or building-book that enframes acts of maintenance, curation, and landscaping. patton (sometimes) resides in and maintains a six-flat in the Glenville neighborhood of Cleveland; the space is both a home and a total work of art. The feature concludes with a chorus of new works celebrating and responding to patton by writers Will Alexander, Carla Harryman, m. nourbeSe philip, Ed Roberson, giovanni singleton, and Cecilia Vicuña.

Jerome Rothenberg (editor), Javier Taboada (editor), The Serpent and the Fire: Poetries of the Americas from Origins to Present

Love that Nick Cave is quoted as saying “No one taught me more about poetry than Jerome Rothenberg.” In their starred review of this collection, Publishers Weekly writes:

Challenging the notion of “American” poetry by including the entire Americas from ancient pre-Columbian cultures to the present, this expansive anthology is divided into thematic “galleries” and “maps,” guiding readers through a maze of poetic innovations and traditions. The first gallery juxtaposes Indigenous oral traditions with European colonizers’ written records, resulting in a powerful dialogue between conquerors and conquered: ‘Mayans started writing when English (even Old English) had yet to be born.

By the seventh century A.D., when English literature made its first tentative appearance, Mayans had a long tradition of inscribing…the walls of temples and palaces, and they had also begun to write books.’ Critical to the anthology’s success is the notion of “omnipoetics,” challenging the hierarchical structures of literary canon formation by exploring ‘on a worldwide scale, toward an anthology of everything.’ The collection features surprising and exciting juxtapositions: Roger Williams appears next to Úrsula de Jesús, followed by a poem by Anne Bradstreet.

This seminal effort redefines what it means to write and read poetry in the Americas. It’s a must-read.

Tilsa Otta, The Hormone of Darkness (trans. Farid Matuk)

“In Tilsa Otta’s emancipatory sensorium, the letters of the alphabet glisten with dew. Words can be used to hold up your hair. Syllables chirp in spectral colors. Names take their place beside the planets. The lights flicker, go out, and Daddy Yankee pulses in the darkness,” Sean McCoy writes in his review of Otta’s poetry collection at The Believer. He goes on:

Many of Otta’s poems are themselves highly musical, and—ably remixed in Matuk’s hands—they make frequent use of rhyme and repetition to produce a trancelike effect. Finally, this is poetry of the singular becoming a multiplicity, of boundaries blurred through coalescing sound and touch.

Otta infuses this blur into her syntax, where the absence of in-line or end-of-line punctuation commonly generates uncertainty as to where one thought begins or ends, prompting us to reach forward and back across lines, across time, beyond our intuition of the possible as we utter “words that never began, like ‘Love,’” and travel the orbits of her verse. “Because this is not a story with a beginning and an end / It’s you and me.

Pedro Espinosa, The Dog and the Fever (trans. William Carlos Williams and Raquel Hélène Williams)

Williams translated this seventeenth-century Spanish text with his Puerto Rican mother, Raquel Hélène. I have to admit I was a bit stumped on this book, if only because, though the spine reads “Quevedo,” recent versions say it’s by Pedro Espinosa, a contemporary of Francisco de Quevedo who collected some of the latter’s poetry into a volume. Apparently El perro y la calentura, novela peregrina was indeed by written by Espinosa and published in a book with Quevedo’s Cartas del Caballero de la Tenaza (Letters of the Knight of Tenaza) in 1625.

Espinosa was a Baroque Golden-Age Spanish poet who studied law and theology was a part of a group of Seville intellectuals. He moved to Madrid where he met Quevedo, Luis de Góngora, and others. Espinosa’s support of the poets he knew drove him to create one of the most treasured anthologies of Golden Age Spain, with almost two hundred and fifty pieces by over sixty authors.

Apparently it was a real mess, however, and is one of the worst examples of typography of the time (likely because of lack of funds). Eventually Espinosa had had it with the secular life, changed his name to Pedro de Jesús, and became a hermit in Antequera. He only wrote religious poetry from then on. Espinosa eventually split his time between priesthood and a hermitage in Ermita de Nuestra Señora de las Cuevas.

Chus Pato, Secession/Insecession (trans. Erín Moure)

Book*hug Press, the publisher of this volume, hosted a conversation between Pato and Moure on its blog. At one point Moure states, “Our lives have crossed in poetry and in translation for over a decade. My wish in translating your work is and was always to invite you into my Canadian poetic culture, so as to perturb it, open new challenges, demonstrate how your work is critical in my own practice of poetry and poetics.”

In response, Pato says, in part,

For a writer, translation is the best of fates and if, on top of translating, the translator-poet writes a new book in response to her translation and reading, I can only be glad. To me, the very spirit of poetry is “I read what you write and I write / You read what I write and you too write.” I can’t conceive of a poet who writes totally on their own; I have never thought of the poet as an absolute and isolated individual: we write poetry so that poetry circulates, so that you, so that I, so that all the six grammatical persons—I, you, she, he, we, they—write and read.

Soledad Fariña, Siempre volvemos a Comala

Fariña, for the uninitiated like myself, is a contemporary Chilean poet who has many accomplishments including the fact she waited to publish her first book until her early forties in order to avoid the problems she saw in other people’s early works. The jacket copy for Siempre volvemos a Comala, which came out last year, states (via, to my shame, Google Translate):

[Here] we find a world that is inhabited and uninhabited at the same time, with a cross between specters that pass through a country that is submerged between the smoke of bombs and History, sustained by dialogues and images permeated by answers to questions as diffuse as they are difficult. What can we understand when the experience is dark?

The author proposes Comala as the territory of the unfinished and thick that was left outside of Time and supports the multiple voices that converge in this work in search of answers that allow them to inscribe in reality what their experiences, dreams and struggles were. It is crucial, in these times, to return to the truncated stories that marked a break in Chile and Latin America by the hand of one of the most important poets of the last decades.

Cecilia Vicuña, Libro Venado/Deer Book (trans. Daniel Borzutzky)

This gorgeous volume, also in my to-read pile, includes Vicuña’s art alongside her words and Borzutzky’s translation. Vicuña in her interview with David Naimon on Between the Covers explains that she first learned of the deer poem through Jerome Rothenberg’s Flower World Variations: A Sequence of Songs from the Yaqui Deer Dance:

The Flower World Variations is not only a total translation….It is a spirit translation because Jerry didn’t know the [Indigenous] language in which these poems were sung. After I encountered the poem, I read it and I instantly translated the twenty Cantos. I didn’t think for a second.

I read it and I translated it immediately. I put it away because it was to me as if the lines of this poem were so full of life, so full of dimensions. If anybody has the patience to discover this poem, it’s a poem that has no beginning or end because it is like a journey in space-time to the ritual of the deer dance.

The deer dance, as I discovered after I began researching it, is probably one of the oldest dances that exist in all continents. Even though scholars believe that this particular one may be five hundred years old, some say two thousand years old, the concept that is behind it as a perception of the relationship between the deer, the land, and the period of language is far, far older. All of that is present in these majestic, minimalist compositions that are circular because everything is repetition and this light, this variations, as if this were a leaf in a tree that moves in a different way.

Lotte Johnson (editor), Chris Bayley (editor), Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics

Published in conjunction with an exhibit with the same title of Schneemann’s work at Barbican, Jane Alison (head of the visual arts arm of Barbican) states,

The title of the exhibition reflects that for Schneemann, the personal was political. She was engaged with an expansive kind of body politics, setting out to challenge the restrictive idea that the body and mind were divided. Schneemann took the sensory experience of her own body as a starting point—she understood her body as inextricably linked with its environment and others and recognized and challenged how history had defined the lives and bodies of women.

However, Schneemann was not only concerned with the specifics of being a woman—in her writing in the 1970s, she reflected on the merits of finding “neutral” instead of gendered terms and furthermore, her body politics engaged with the abuse of power across global conflicts. Schneemann was a trailblazer, whose work defies easy categorization. Known predominantly as a performance artist, she was adamant throughout her life that she was foremost a painter.

This volume includes Schneemann’s work as well as words from Eileen Myles, Jennifer Doyle, and others.