The Annotated Nightstand: What Sergio de la Pava Is Reading Now, and Next

Riv, a Colombian-American man who self-describes as a “poet/philosopher/private eye?” has fled New York City after a nebulous emotional injury. “I was running. Away or to or from, I didn’t know,” he says.

Whatever his trajectory, Riv ends up in the city of Cali with no plans, though that all coalesces around him quickly. He connects with his cousin, Mauro, with whom he converses between their patchy English and Spanish. Mauro connects Riv to a desperate and wealthy woman whose daughter is missing. Riv plays off his investigative abilities (“I can probably find a body as well as the next guy”), and yet, despite wryly insisting he’s a twerp, Riv is smart, capable, and inventive.

We follow him through his investigative process, with Mauro as a witless Watson to his Sherlock (and another cousin, Fercho, soon brought into the fray). The interactions between the three cousins are a riot, with Fercho and Mauro the foil to Riv’s sharp wit.

The local cousins quickly realize this isn’t simply a case of a missing person—the lost daughter is somehow connected with Exeter Mondragon, a brutal man who holds the whole city in his grip. Mauro, attempting to talk Riv out of pursuing the case, says, “Poor beauty. She’s a cube of ice that just got dropped into the wrong drink, probably thought she could keep from melting.”

Like any hardboiled noir, the surveilled become those who surveil, corruption seems endless, and nothing is as it seems—though the depths of this last gesture get wilder than you might imagine. Lisa Rorhbaugh writes in a starred review at Library Journal, “Readers will want to strap in tight as De La Pava (Lost Empress) takes them on a wild, turbulent ride with a likable narrator, Rivilerto ‘Riv’ del Rio, who is both a private eye and a philosophical poet.”

The VERDICT? “This fantastical, spectacular, riveting tale is incredibly well-written, and it gives off a vibe that is fiercely intense and consuming. An existential detective thriller from an engaging writer and thinker.”

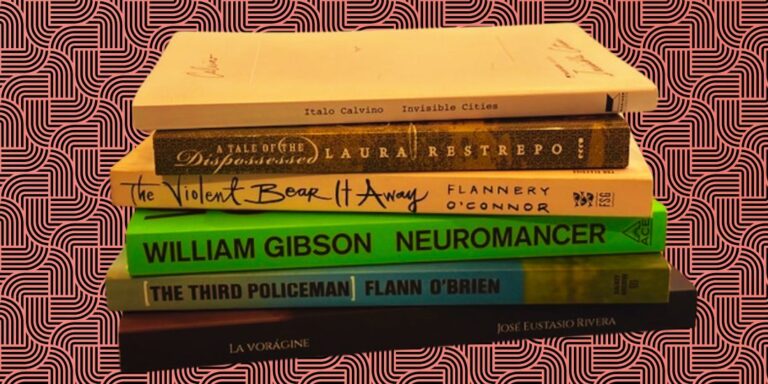

On his to-read pile, De la Pava states: “What a pile of judgement is pictured here. That you have lived so long to read so little. Luckily, novels suspend time.”

*

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (tr. William Weaver)

“Invisible Cities is a new book by Italy’s most original storyteller, Italo Calvino. But this time not a book of stories. Something more.” So begins the original 1974 review of Calvino’s masterpiece in the New York Times by Joseph McElroy. McElroy goes on:

The wonderful phenomena of Invisible Cities are seen as through some unfolding nuclear kaleidoscope. Past and future possibility grow out of the prison of an “unlivable present, where all forms of human society have reached an extreme of their cycle and there is no imagining what new forms they may assume”….Why does the emperor ask the traveler to tell him what is in his empire? Partly because the emperor cannot know what is in it. Perhaps because he may wish not to know, but also because he must wish to feel in its deterioration some chance of growth.

As a kind of wild sidebar, the translator, William Weaver, was an American who studied in Rome, and served as an American Field Service ambulance driver in Italy during WWII. He stayed for decades. Weaver translated a slew of Calvino’s works, as well as Umberto Eco, Primo Levi, and many others. He also had a hand in translating Italian libretti and was a Metropolitan Opera commentator.

Laura Restrepo, A Tale of the Dispossessed: A Novel (trans. Dolores M. Koch)

“Vividly detailed, a florid fantasy that suggests the miraculous potential of hope and love in the midst of perpetual war,” writes Kirkus in its 2004 review of A Tale of the Dispossessed.

The nameless narrator (presumably from the US) meets the man known as Three Sevens in the refugee shelter where she works. She is attracted to him, but he speaks only of a woman named Matilde Lina. The mysterious man, she learns, was born in 1950, in Santa Maria Bailarina, a village named after its patron saint, the Dancing Madonna. Found on the church steps, the infant had an extra toe (hence Three Sevens, after twenty-one digits), which signals something supernatural. He’s taken in by the village laundress Matilde Lina, and, after a massacre a few months later, the survivors take to the road, carrying the wooden sculpture of the Dancing Madonna with them for protection. The slow march lasts for years. “We were victims, but also executioners,” Three Sevens admits.

Flannery O’Connor, The Violent Bear It Away

As a poet and nonfiction writer I have known O’Connor and her work, but didn’t realize she had died so young: at thirty-nine, of lupus. While she struggled with the debilitating effects of the disease over a dozen years, she wrote her two novels (including The Violent Bear It Away), over twenty short stories, and gave over sixty readings and lectures.

This novel, like so much of O’Connor’s work, attends to existential terrors of faith—in this case a Francis Tarwater who was kidnapped by his grand-uncle Mason. Mason attempted to brainwash Francis into thinking Mason was a prophet and Francis would assume his efforts upon his grand-uncle’s death. Mason’s death is the inciting incident of the grim novel.

As a total sweet aside, apparently O’Connor loved birds. She had dozens of domesticated birds on her farm, as well as emus, toucans, and other exotic fowl. As a teen, she sewed a full outfit for her duck and brought it to school. In a conversation with Rosemary M. Magee, O’Connor said, “When I was six I had a chicken that walked backward and was in the Pathé News. I was in it too….I was just there to assist the chicken but it was the high point in my life. Everything since has been an anticlimax.”

William Gibson, Neuromancer

“Neuromancer was the first cyberpunk novel. It won the Hugo and Nebula Awards for 1984, which is the sci-fi writer’s version of winning the Goncourt, Booker and Pulitzer prizes in the same year,” writes Martin Walker in the Mail & Guardian.

[Gibson’s] short stories in Omni Magazine had already begun to earn him a name, but Neuromancer invented a genre. It begins in Japan, the seamy underside of Tokyo, with a loner called Case. He used to be a brilliant cowboy surfer of the data nets, a thief who stole corporate software for even richer thieves. When he tried to steal something for himself, they burned out his nervous system, and he is reduced to hustling. From then on, it’s a cybernetic western, a solitary anti-hero who uses his contacts of the scum world to recover his skills, go up against the big, bad guys, confound their knavish tricks and survive.

I love this quote from Gibson, considering the tech in the novel:

I wrote Neuromancer on an olive-green Hermes portable typewriter, a 1927 model, that looked to me as the kind of thing Hemingway would have used in the field. Even now, I write on an ancient Mac, and my son has the real powerboard….When he trades up, that’ll go to my daughter, and her rig will go to my wife, and I’m at the bottom of the food chain.

(Also check out this amazing first cover.)

Flann O’Brien, The Third Policeman

At NPR, Chris Lehmann writes of The Third Policeman,

The Third Policeman, originally published in 1944, is the singularly strange crowning work in the fiction of the great Irish humorist Flann O’Brien. It opens with a tale of robbery and murder committed by its nameless narrator, who intends to use the proceeds of the crime to publish his commentaries on the writings of a plainly cracked philosopher named de Selby—who theorizes that the earth is actually shaped like a sausage and that the phenomenon of night is a form of industrial pollution. From there on, the book only gets stranger. The narrator finds himself in an alternate dimension not unlike the area surrounding his rural Irish home, but running on an entirely different set of metaphysical laws. The area policemen closely monitor the movements of local citizens, convinced that they are gradually being turned into bicycles. Violent one-legged men roam the countryside. And eternity is an elevator ride away, just to the left of the local river.

José Eustasio Rivera, La Vorágine

Set in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century in Colombia during the rubber boom, La Vorágine (in English, The Vortex) is considered one of the most important pieces of Latin American literature. The jacket copy for John Charles Chasteen’s 2018 translation states,

Published in 1924 and widely acknowledged as a major work of twentieth-century Latin American literature, José Eustasio Rivera’s The Vortex follows the harrowing adventures of the young poet Arturo Cova and his lover Alicia as they flee Bogotá and head into the wild and woolly backcountry of Colombia. After being separated from Alicia, Arturo leaves the high plains for the jungle, where he witnesses firsthand the horrid conditions of those forced or tricked into tapping rubber trees. A story populated by con men, rubber barons, and the unrelenting landscape, The Vortex is both a denunciation of the sensational human-rights abuses that took place during the Amazonian rubber boom and one of the most famous renderings of the natural environment in Latin American literary history.

Apparently, the novel was so successful Rivera was elected to the Investigative Commission for Exterior Relations and Colonization the year after La Vorágine’s publication and was outspoken about the abuses of rubber workers and the misuse of the land.