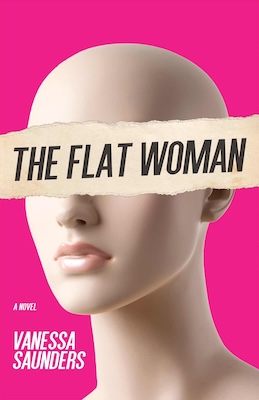

“The Flat Woman” Asks What Came First, Climate Change or Sexism?

In Vanessa Saunders’ novel The Flat Woman, seagulls fall dead from the sky, ash poisons the air, and women are blamed for a climate crisis caused by a soda pop/prison/hotel megacorporation. For the narrator, “the woman,” this is all particularly personal. Her mother has been arrested for alleged seagull ecoterrorism, and the woman has what she calls “leaky boundaries”—she literally experiences parts of the natural world (grass, fish, feathers) inside her body. Hiding these things from everyone but her enigmatic aunt, the woman moves in with a climate activist/Elvis impersonator who ultimately turns violent toward her.

Surreal, funny, repulsive, and brilliantly thought-provoking, The Flat Woman is an example of what bold and original climate writing can do. At every turn, it complicates the intersection of public and private traumas. After all, what does it mean to miss your mother when the natural world is dying all around you? And if you can’t or won’t fight climate change, how can you stand up to your abusive boyfriend? Ultimately, Saunders’ speculative dystopia demands the reader acknowledge two truths, neither forgivable: we are largely powerless within institutional systems of harm; and most of us are complicit in the most quotidian of ways, by failing to act in the face of evil.

Saunders and I spoke over Zoom about humor as an antidote to despair, how representations of women’s pain have trained us to accept violence, and ethics in the age of information overload.

Rachel Taube: You’ve said that this book began as a way to process the violence that had been inflicted on you in your own relationships with men. You also wrote: “What surprised me was this: while this was supposed to be a book about male violence against women, the story also centers my villainy.” Can you elaborate on that transformation and what you mean by “villainy”? How did this come to be a book about climate change?

Vanessa Saunders: I think that victimhood is very comfortable and easy, but victimhood as it intersects with villainy is a lot more interesting to me artistically. In the context of this project, I was thinking about my relationship to worsening climate change. Thinking through a lot of small choices that I made, often very thoughtlessly and lazily. The book became a way of working out ways in which I was in the wrong even as I processed ways in which I had been socialized to become a victim of violence. And I’m not here talking about physical violence, but there were definitely quite a few emotional things that I was just—oof, that should not have been that situation, you know? You can see ways in which women’s pain, women’s anger, and violence against women have been represented in stories, and you can see how these stories have trained us to accept violence, to stifle anger, to silence pain.

When you’re a kid, I think you expect to become a certain type of person we also see in stories, quite a heroic character. And then you grow up and a lot of people are bystanders of a lot of harm. And occasionally people are also aggressors as well. In the time in which we live, this age of information, this question of ethics becomes more intense because we have a lot more access to and information about all the horrible things that are happening. And this can be incredibly uncomfortable, especially since many of us don’t do the right thing with the information that we have, and I think that can cause a lot of anxiety.

Interestingly, the decision to write about climate change wasn’t originally part of my plan. But it was a product of what I was subconsciously thinking about.

RT: I’m interested in what you said about how women’s stories train us to accept violence. Do you feel like stories about violence against women have trained us to accept climate change?

VS: Actually, yes. Because so many of them are just doom and gloom, oh this horrible thing is going to happen. That’s been done. We need to think about new ways to talk about these kinds of stories, in ways that aren’t just straight depressing, because that’s just prefabricated thought. That’s just not interesting.

RT: Let’s dig into where climate change meets violence in this book: The Flat Woman is full of dead birds—their feathers, their blood. In the latter half, there are also several grotesque scenes of cows being slowly run down in the street or eaten by vultures. Most people in the novel, absurdly, ignore this violence. But as a reader, I felt repulsed pretty viscerally, in particular because of the narrator’s “leaky boundaries.” Do you think the reader has—or do we want to have?—leaky boundaries?

VS: I feel like you’re reading it here as kind of like a hyper empathy or affinity with the natural environment. If we’re thinking about gender in this essentialist way, leaky boundaries would be a form of ecological care, which is certainly better than not caring. Interestingly, her physical condition does not translate to a broader sense of action or justice against the environment. It actually is the opposite, where she ends up working for this company that is ruining the planet and incarcerating her mother. It’s also worth mentioning that this is a very uncomfortable position to be in: taking in the pain and the ephemera of the world. In the case of climate change, most people have probably cut themselves off from their leaky boundaries.

RT: Do you have a preferred reading of leaky boundaries, or intention?

VS: I think it could be read as an allegory for mental illness. Or it could also be read as a metaphor for rape culture and the general state of women’s bodies, especially in America. Women do go through a lot of crazy transformations in their life, with puberty, menopause, and, for some people, pregnancy and childbirth. So, the female body is kind of this porous, unstable vessel. And if we think about that in the context of rape culture, the woman is seen as an object that is permissible to dominate or take control over. We do live in a country where women don’t have the federal right to abortion. I live in Louisiana, and I can’t get an abortion even if it was medically necessary, though there’s some ambiguity. So, I think it could speak to the ways in which women’s bodies are seen as permeable objects, and the lack of control that women have and autonomy over their own bodies, some of it being biological and other elements of it being social.

RT: You mentioned how overwhelming empathy can be, so I’d like to turn to another way to talk about climate change, which is absurdity and humor. This is a really funny book, in the most dystopian way. One example, the boyfriend, a self-described climate activist, has all the right language about corporate greed and privilege and personal responsibility—and uses them equally to abuse his girlfriend and promote his Elvis impersonator act. It’s terrifying and funny—or so terrifying it is funny? So, talk to me about the Elvis impersonators. More broadly, I’m wondering if you have thoughts about how humor or satire can be used as a revolutionary tool in writing.

VS: I’m from the Bay Area, and I started at San Francisco State in 2008. At that time San Francisco was very much a city dominated by queer culture, and a specific representation of masculinity that was very camp, very in your face, and I think queer-coded. It was totally normal for me to get onto the MUNI at noon on a Tuesday and see someone get on in a tutu, nipple tassels, shirtless. Another thing that I might have been thinking about subconsciously was the idea of the gurlesque, which is a kind of poetics theory that Lara Glenum and Ariel Greenberg came up with. Basically, these female poets that perform their identity in a really exaggerated or amplified way, as a form of taking back the gender identity that has repressed you and traumatized you and defiantly making fun of it but in a way that kind of reclaims the power.

It feels like we’re a culture that’s very preoccupied with looking backwards, because we’re terrified to think about what’s ahead.

I felt like it was important to write about climate change in a way that was not morbidly depressing. I know that one of my favorite authors, Ben Lerner, talked about how love is an antidote to despair, and I think that humor is as well. I think that if you can write a story about climate change that is funny and ridiculous—I thought it would be a way to dismantle the way that this issue is thought about, and to provoke something that’s more true and I guess more frustrating about climate change: We can laugh at it, there’s also something that you can do about it.

RT: Let’s get down to the line level. I can see your poetry background in the way the novel’s language often shirks a kind of emotional labor. The text comes fast and unpredictable. Incomplete sentences keep the reader at a distance, keep the narrator at a distance from herself. The book, of course, is called The Flat Woman, and there are references throughout to the “flat” tones and expressions of the narrator and her boyfriend. Sometimes, this flatness felt like an experience of trauma. Other times, it felt like the narrator’s refusal to reckon with her complicity. Can you talk about how you settled on the tone, and what flatness implies to you?

VS: The flat woman was actually the first line of the book, before I ever came up with anything else. She did not have a name. You have impulses as an artist and then later on, you actually really understand why you made certain decisions. I think it was my decision to play with certain representations of stories about women growing up who I felt were often super one-dimensional and flat. I’ll never forget watching one of the James Bond movies, and he has this movie-long narrative about this romance. In the sequel, the woman is gone, she is never addressed or explained, she’s just totally absent. I remember being profoundly upset by that as a kid. This was my attempt to integrate that kind of flatness into a story of feminist critique. Of course she’s not going to stick up for herself when she’s getting abused. Do any of the paper-thin protagonists in the fairy tales ever draw attention to the violence that’s being inflicted against them? In a story about violence against women, flatness has an important role in providing a connection to stories outside of the text.

The other part of it is that, yes, she is flattened by trauma. One way to read it is the trauma of the access to information. Her trauma isn’t just personal, it’s also public. I think the source of the flatness was always somewhat universal, in the trauma of girlhood and the trauma of exposure to a world built on exploitation of the vulnerable.

RT: I was struck by the line, “[T]he grief pattern of a bird is relentless flight. This is the only known grief pattern of a bird.” There’s grief surrounding the narrator’s absent, imprisoned mother; and there’s also a strong sense of climate grief, at least for the reader. They feel equally absurd and senseless. What happened when you put these ideas side by side?

VS: In a way, this was trying to make something public, which was the experience of mass extinction, into something very personal. What has struck me always about my personal experience with grief is how eager people become to blame someone over the death. That’s part of what got me interested in questions of responsibility ethics in disasters. But as a writer—the mode of poetry is, I think, largely preoccupied with universals. Fiction has the same preoccupations, but you’re trying to figure out ways in which you can explore universals through the particularity of a character. I wanted to put those two things in conversation with each other, and to explore how hard the simultaneous experience of both can really be.

One thing that my husband and I talk about a lot is how our culture is today in a kind of a state of arrested development, with all these nostalgia bands, resurgence of old movies, it feels like we’re a culture that’s very preoccupied with looking backwards, because we’re terrified to think about what’s ahead. And maybe that’s where kind of that flatness comes from, which is this overwhelming feeling of grief, but then feeling like you need to repress those overwhelming feelings, to the point where you just become very apathetic.

RT: The narrator is experiencing this public or climate grief very differently than the only male character, her boyfriend. I got the sense that, between the narrator, and her aunt, and the woman protester who burns herself alive, not only are women having this grief experience but maybe they also have some unique responsibility to react to climate change in a certain way—a particular power or opportunity, to at least protest.

VS: I think you’re picking up something really important about the book that we haven’t talked about yet, which is: It’s not just a question about blame, but also thinking about blame in the context of feminism. It’s easier to blame a woman for something than a man. It’s not only the lack of male privilege, but there are some qualities that people tend to naturally ascribe to women, which would be maybe a predilection for instability or being crazy or hysterical. Another part is, we kind of expect more empathy and less selfishness from women.

We are being asked to sacrifice our own livelihoods for the personal gain of a very small group of corporate and politicians who are in power.

In the story, women are unquestionably held responsible for climate change, and then there are small pockets of women revolting against climate change at the same time. We know that women take on a lot that they don’t necessarily need to, internal pressures that women feel based on responsibilities that are gendered in society. Perhaps these women are revolting because they feel this sense of inherent guilt that the men are not subjected to. And maybe that guilt and responsibility is a good thing in the end—but it would be easier to not feel that sense of responsibility.

RT: I can’t end the interview without asking about this line, which stopped me in my tracks: “She begins to count down from ten. If I get to one and his hands are still on my neck, she thinks, I will ask him to stop.” As he’s choking her, her boyfriend is lecturing her about the climate crisis. I found I could reframe her thought in those terms, too: if we get to 1.5 degrees, say, we will ask corporations to stop their endless pollution. But there’s a hesitation, because if we do ask them to stop, it’s going to change everything, and we’ll have to admit how bad things really are. Can you talk to me about this moment in the novel?

VS: What you’re picking up on there is kind of the doubleness, which comes from the parable, or the allegorical qualities, which came from this project staying in the poetry genre for so long. That moment is kind of a parallel to our own relationship with harmful systems. I feel like we could be in a little bit of an abusive relationship with the powers that be, in the sense that we are being asked to sacrifice our own livelihoods and the livelihoods of our descendants for the personal gain of a very small group of corporate and politicians who are in power.

It becomes interesting as an ethical question: What is your responsibility in a situation where you truly lack power? Most of us are in the position of being strangled. We are a woman being strangled, maybe without the physical ability to fight back. It’s a moment where she’s rationalizing what’s happening, because she has no power to stop him. And then I thought about it more: She doesn’t even ask him. Right? She doesn’t ask him to stop. So, maybe she has more power than she thinks she has. Maybe if she were to try to stick up for herself, then something would be disrupted in what’s going on between them. I think that there is a lot of power in mass action, but this book looks at the parts of us that don’t want to engage in that kind of activity, and some of the reasons why. The parts of us that are traumatized, exhausted, or just intrinsically selfish. And these behaviors are part of human reality, but I don’t think they get integrated into a lot of stories, especially about climate change and disaster, because those are often centered around heroic characters who are likeable and do likeable things.

The post “The Flat Woman” Asks What Came First, Climate Change or Sexism? appeared first on Electric Literature.